Moominvalley in November (8 page)

Read Moominvalley in November Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Family, #Classics, #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Friendship, #Seasons, #Concepts, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish

CHAPTER 10

Late That Night

I

T

was dark in the tent. Snufkin crept out of his sleeping-bag, the five bars had come no nearer. Not a sign of any music. Outside it was very quiet, the rain had stopped. He decided to fry some pork and went to the woodshed to get fuel.

When the fire was alight the Hemulen and Fillyjonk came down to the tent again and stood there watching without saying anything.

'Have you had dinner?' Snufkin asked.

'We can't,' the Hemulen answered. 'We can't agree about who's going to do the washing-up.'

'Toft,' said Fillyjonk.

'No, not Toft,' the Hemulen said. 'He's helping me in the garden. Fillyjonk and Mymble ought to keep house for us all, the womenfolk should do these things, eh? Don't you think I'm right? I can make the coffee and see to it that everybody has a nice time. And Grandpa-Grumble is so old, I'll let him please himself what he does.'

'Why do hemulens have to organize things for other people all the time!' Fillyjonk exclaimed.

They both looked at Snufkin anxiously and expectantly.

Washing-up, he thought. They don't know a thing about it. What is washing-up? Tossing a plate into the stream, rinsing one's paws, throwing away a green leaf, it's nothing at all. What are they talking about?

'Isn't it true that hemulens want to organize things the whole time?' Fillyjonk asked. 'This is important.'

Snufkin got up, he was a little scared of both of them. He tried to think of something to say, but he couldn't find an explanation that seemed fair.

Suddenly the Hemulen shouted: 'I won't organize a thing! I want to live in a tent and be independent!' He tore open the tent door and crept inside, filling the whole tent. 'You see what I mean,' Fillyjonk whispered. She waited for a moment or two and then went away.

Snufkin lifted the frying-pan off the fire, the pork was quite black. He filled his pipe. After a while he asked cautiously: 'Are you used to sleeping in a tent?'

The Hemulen answered gloomily: 'Living in the wilds is the best thing I know.'

It was now quite dark. Up at the house two windows were lit and the light was just as steady and just as soft as it always used to be in the evenings.

*

In the guest room facing north Fillyjonk lay with the blanket pulled up round her nose and her head full of curlers which hurt her neck. She lay counting knots in the ceiling and she was hungry.

All the time, right from the beginning, Fillyjonk had thought that she would be the one to prepare the food. She loved arranging small jars and bags on the shelves, she thought it was fun to work out new ways of doing up left-overs in puddings and rissoles so that nobody could recognize them. She loved doing the cooking as economically as possible, and knowing that not a single drop of semolina had been wasted.

The family's great gong hung on the veranda. Fillyjonk had always longed to be the one who announced dinner, making the sonorous brass resound, dong dong, through the valley until everybody came running and shouting: 'Food! food! What have you got for us today? We're so hungry!'

Tears came into Fillyjonk's eyes. The Hemulen had spoilt everything for her. She would willingly have done the washing-up, provided it had been her own idea. Fillyjonk should look after the housekeeping because that's what womenfolk do! Huh! And with Mymble, what's more!

Fillyjonk put out the light so that it wouldn't burn quite unnecessarily and pulled the blanket over her head. The stairs squeaked. A very, very faint rattling sound came from the drawing-room. Somewhere in the empty house someone shut a door. How can there be so many sounds in an empty house, Fillyjonk thought. Then she remembered that the house was full of people. But somehow she still thought it was empty.

*

Grandpa-Grumble lay on the drawing-room sofa with his nose buried in the best velvet cushion and heard somebody creeping into the kitchen. There was a very faint sound of clinking glass. He sat up in the dark and pricked up his ears and thought: they're having a party.

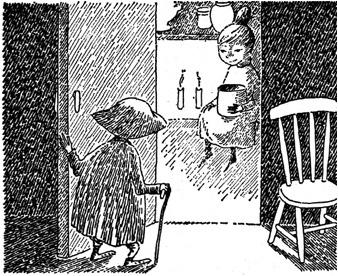

Now it was quite quiet again. Grandpa-Grumble went across the cold floor and crept up to the kitchen door. The kitchen was dark, too, but a ray of light shone from under the pantry door.

Aha, he thought. They've hidden themselves in the pantry. He jerked open the door, and there sat Mymble eating pickled gherkins, with two candles burning on the shelf beside her.

'So you had the same idea,' she said. 'There are the pickled gherkins and there are the cinnamon biscuits. Those are mustard pickles, you'd better. not eat them, they're too strong for you.'

Grandpa-Grumble immediately took the jar of pickles and started eating. He didn't think they were much good, but he went on eating them all the same.

After a while Mymble said: 'They'll upset your stomach. You'll explode and drop dead on the spot.'

'One doesn't die on holiday,' Grandpa-Grumble said cheerfully. 'What's that in the soup tureen?'

'Spruce-needles,' Mymble answered. 'They fill their stomachs with them before they hibernate.' She lifted the lid: 'The Ancestor seems to have stuffed most of them.'

'What Ancestor?' Grandpa-Grumble asked, surreptitiously changing over to gherkins.

'He's in the stove,' Mymble explained. 'He's three hundred years old and is hibernating just now.'

Grandpa-Grumble said nothing. He couldn't quite decide whether he felt pleased or offended that there was someone who was even older than himself. His interest was aroused and he made up his mind to wake up the Ancestor and make his acquaintance.

'Listen,' Mymble said, 'it's not worth trying to wake him up. He won't wake up till April. You've got through half that jar of gherkins.'

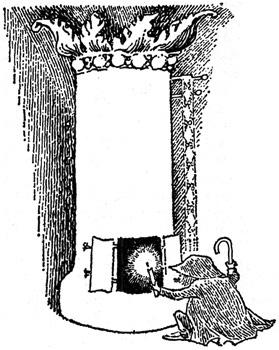

Grandpa-Grumble snorted and screwed up his face, stuffed his pockets with gherkins and cinnamon biscuits, took one of the candles and shuffled back into the drawing-room. He put the candle on the floor in front of the stove and opened the doors. There was nothing but darkness inside. He lifted the candle into the stove and looked again. All there was was a piece of paper and a little soot that had fallen down the chimney.

'Are you there?' he called. 'Wake up! I want to see what you look like!' But the Ancestor didn't answer; he was hibernating with his stomach full of spruce-needles.

Grandpa-Grumble picked up the piece of paper and saw that it was a letter. He sat on the floor and tried to remember where he had left his glasses. But he couldn't. Then he hid the letter in a safe place, blew out the candle and crept in among the cushions again.

I wonder whether the Ancestor is allowed to join in when they have a party, he thought gloomily. Never mind.

I'

ve had a very enjoyable day. A day that's been my very own.

*

Toft lay in the box-room reading his book. The light at his side made a little circle of safety in this strange, great house.

'As we intimated earlier,' Toft read, 'this curious species gathered its energy from the electrical charges which regularly accumulated in these elongated valleys and illuminated the night with their white and violet light. We can picture to ourselves the last of this virtually extinct species of Nummulites gradually rising to the surface, struggling towards the boundless swamps of the rain-drenched forests where the lightning was reflected in the bubbles rising from the ooze, and finally abandoning his original element.'

He must have been really lonely, Toft thought. He wasn't like any of the others and his family didn't bother about him, so he left. I wonder where he is now and whether I shall ever be able to meet him. Perhaps he'll show himself if I can describe him clearly enough.

Toft said: end of the chapter, and put out the light.

CHAPTER 11

Next Morning

I

N

the long, vague dawn as the November night changed to morning, the fog moved in from the sea. It rolled up the hillsides and slid down into the valleys on the other side and filled every corner of them. Snufkin had determined that he would wake up early in order to have an hour or two to himself. His fire had burnt out long ago but he didn't feel cold. He had that simple but rare ability to retain his own warmth, he gathered it all round him and lay very still and took care not to dream.

The fog had brought complete silence with it, the valley was quite motionless.

Snufkin woke up as quickly as an animal, wide awake. The five bars had come a little nearer.

Good, he thought. A cup of coffee and I'll get them. (He ought to have skipped the coffee.)

The morning fire picked up and began to burn. Snufkin filled the coffee-pot with water from the river and put it on the fire, took a step backwards and tumbled over the Hemulen's rake. With a terrible clatter his saucepan rolled down the river bank, and the Hemulen stuck his nose out of the tent and said: 'Hallo!'

'Hallo!' said Snufkin.

The Hemulen crawled up to the fire with the sleeping-bag over his head, he was cold and sleepy but quite determined to be amiable. 'Life in the wilds!' he said.

Snufkin saw to the coffee.

'Just think,' the Hemulen continued, 'being able to hear all the mysterious sounds of the night from inside a real tent! I'm sure you've got something for a stiff neck, haven't you?'

'No,' said Snufkin. 'Do you want sugar or not?'

'Sugar, yes, four lumps preferably.' His front was now getting warm and the small of his back didn't ache so much any more. The coffee was very hot.

'What's so nice about you,' said the Hemulen confidentially, 'is that you are so little. You must be terribly clever because you don't say anything. It makes me want to talk about my boat.'

The fog had lifted a little, quite quietly, and the black wet ground began to appear around them and round the Hemulen's big boots, but his head was still in the fog. Everything was almost as usual, except his neck. The coffee warmed his stomach and suddenly he felt gay and without a care in the world: 'You know what,' he said, 'you and I understand each other. Moominpappa's boat is down by the bathing-hut. That's where it is, isn't it?'

And they remembered the jetty, narrow and solitary, resting shakily on blackening piles and the bathing-hut at the end of it with its pointed roof and red and green window-panes and the steep steps leading down into the water.