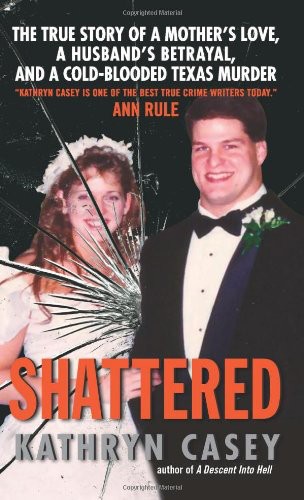

Shattered: The True Story of a Mother's Love, a Husband's Betrayal, and a Cold-Blooded Texas Murder

Authors: Kathryn Casey

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #True Crime, #Murder, #Case Studies, #Trials (Murder) - Texas, #Creekstone, #Murder - Investigation - Texas, #Murder - Texas, #Murder - Investigation - Texas - Creekstone, #Murder - Texas - Creekstone, #Temple; David, #Texas

The True Story of a Mother’s Love, a Husband’s Betrayal, and a Cold-Blooded Texas Murder

For my husband, with love

These things are an abomination unto God: A proud look, a lying tongue, and hands that shed innocent blood.

Proverbs 6:16-17

It couldn’t be true. At any moment the nightmare would…

Parents loom large in their children’s lives. They take on…

Railroad tracks run through the center of Katy, Texas, the…

At the time Belinda Lucas and David Temple enrolled at…

In her third year at SFA, Belinda was thriving. She…

All of us knew that Belinda loved David with all…

I liked Belinda right off. We just automatically clicked, and…

When it came to football, Coach Temple was aggressive,” says…

The thing about Quinton and David is that they were…

The holidays approached, and Brenda called Belinda late that fall,…

The 911 call came in at 5:36 that afternoon, January…

At the same time David cried into the telephone and…

At Bunco, the women were beginning to wonder. Belinda loved…

Detectives are taught the circle theory, that in a homicide…

Late that night, one of David’s uncles called Paul Looney,…

That afternoon, the first day after Belinda’s murder, David and…

That Wednesday, the Katy Times ran its first piece on…

In a Houston Chronicle article that ran three days after…

At Hastings Ninth Grade Center on Friday, an unknown student…

After the funeral, Brenda told the rest of her family…

Eleven days after her daughter’s murder, Carol called Chuck Leithner.

On the forensic front, results continued to dribble in. Gunshot…

Heather didn’t want to talk about the murder. She got…

In February, Debbie and Cindy ran a full-page remembrance of…

Fall came and the football season began. To the surprise…

On the first day of January 2000, Belinda Temple’s murder…

One day, in his living room in Nacogdoches, Tom watched…

While Schmidt and Holtke drove David to the jail for…

Courtrooms are uncomfortable places, especially during high-stakes trials. On the…

Despite all Siegler’s bits and pieces, many in the courtroom…

Some names and identifying characteristics have been changed in this book. They include: Hillary Brooks, Jimi Barlow, Jeremy Rakes, Corey Reed, Howard Robert Gullet, Ed, John, and Billy Kramer.

I

t couldn’t be true. At any moment the nightmare would end, and Belinda Lucas Temple would be alive.

As on any other day, Belinda’s parents would answer their telephone and hear her say, “Mops and Pops, it’s Number Five.” Or Belinda and her twin sister, Brenda, would gab, just happy to hear each other’s voice. They bantered regularly about their jobs and their lives. But mostly Brenda was content to listen as Belinda rattled happily on about her children. Evan was three, a burly, shy little boy, and the center of his mother’s life. Although she wasn’t scheduled to enter the world for another month, baby Erin, too, had already claimed a Texas-size chunk of her mother’s heart. A pretty, energetic woman with lush golden-brown hair, Belinda often ran her hands over her round belly, undoubtedly anticipating the joy of the first time she’d hold her infant daughter in her arms. Was there anything more breathtaking than the softness and smell of a newborn? Any sound more heart melting than a cooing infant?

At the very mention of her children, Belinda’s face, her entire demeanor, visibly glowed with the deepest of loves.

Monday, January 11, 1999, however, wouldn’t be just another day in Creekstone, a quiet Houston suburb, and Belinda’s family and friends would never recover from the heartbreak of that warm winter day that started like any other only to end in unfathomable tragedy.

Late that afternoon, Belinda’s high-wattage smile vanished, forever. No one would ever again hear the soft lilt of her East Texas accent or see the sparkle in her expressive green eyes. The nursery on the second floor of the Temples’ house, the one Belinda painted a color she dubbed “Big Bird” yellow, would never be used. The crib with its blue-and-white-plaid linens would remain empty, and baby Erin would never draw a first breath.

Murdered? Executed. But what kind of monster would kill an expectant mother and her unborn child?

Yet, it was true. And the reality was horrifying beyond description.

At sunset the usually sedate, middle-class neighborhood roiled with tension, as patrol cars lined the streets and officers strung crime-scene tape across the front yard of 22502 Round Valley Drive, Belinda and David Temple’s meticulously kept redbrick two-story home. TV news stations rushed reporters and cameramen to the scene, as helicopters hovered overhead in the early evening winter darkness.

No one could have imagined the misery that waited inside that house.

So full of energy and kindness that her fellow high-school teachers called her the “Sunshine Girl,” Belinda’s cold, motionless, heavily pregnant body lay sprawled on a carpeted closet floor. A contact wound from a shotgun at the back of her head had shattered her skull, and what remained of her face was frozen in a grotesque death mask that recalled Edvard Munch’s disturbing expressionist masterpiece,

The Scream

.

Like that of the strange, distorted figure in the painting, Belinda Temple appeared destined to forever silently cry out in utter agony.

Outside on the street, Belinda’s husband stood next to a squad car, surrounded by his parents. His mother wept. His father appeared shaken and crestfallen. But David, a thick-necked, massive man who’d been a high-school and college football star, stood stoic, not shedding a tear. His wife and baby daughter had been brutally murdered, but to many on the scene, the young father didn’t even look upset.

Perhaps it wasn’t surprising that before long, the investigators eyed David Temple with suspicion. Still, could a husband and father do something so vile?

On his frantic call to 911, David said he’d returned from an outing with Evan and found the back door open and his wife’s bloody, lifeless body. Shards of glass from the door’s window littered the den floor, and drawers gaped ajar in the dining room. The crime scene unit photographed a television off its stand and lying on its side. Could the detectives’ instincts be misleading them about David Temple? A popular high-school football coach, the man was a local legend, a small-town hero. How could he be a suspect? Wasn’t it more likely that a would-be thief discovered he wasn’t alone in the house and panicked?

That awful night on Round Valley Drive dissolved, leaving behind a long list of unanswered questions. Then the first week after the murders faded into memory, trailed by the first month, and the first year. One after another the years that followed extinguished without an arrest, while Belinda’s and baby Erin’s bodies lay in a sealed coffin, buried six feet under a rose granite headstone that read:

We feel the touch of angel wings

.

Yet, although time passed, they were never forgotten.

Detectives grew to expect to hear Belinda’s dad, Tom Lucas, on the telephone, prodding for news. “What’s happening?” he asked, his gruff voice thick with the unimaginable pain of a parent of a murdered child. “What can you tell me about what you’re doing to solve this case?”

They didn’t fault Lucas for calling, but the detectives could offer little reassurance. The Temple murder case was stalled, and some feared it would remain that way. If pressed, those who’d worked the scene would have admitted the distinct possibility that those who loved Belinda might go to their own graves without closure.

Meanwhile, in his cubicle in a run-down county building on Houston’s east side, one detective in particular, an avuncular man with a brown flattop named Mark Schmidt, couldn’t let go of the Temple case. It haunted his waking hours and invaded his thoughts each night as he closed his eyes hoping for sleep. Over and over again, Schmidt relived the night Belinda and Erin died, wondering what should have been done, what could have been done to solve the murders. Every time he read about a new forensic breakthrough, Schmidt resubmitted the Temple evidence. But no matter what he tried, the murder books on the case, the loose-leaf binders that held everything from the shocking autopsy photos to witness statements, sat on his desk collecting dust.

As the world went on about its business, Belinda Temple and her baby waited for justice. Would it ever come?

P

arents loom large in their children’s lives. They take on mythical proportions, even as their offspring age. A father’s hands may always be remembered as strong, even after they’ve withered from arthritis. A mother’s words have the power to endure even after death, in the memories of her children. Their laughs and their smiles may haunt as much as warm their children into middle age and beyond. If in the end Tom and Carol Lucas devoted themselves to the memories of Belinda and their unborn granddaughter, theirs wasn’t a family of Norman Rockwell images and Currier and Ives Christmases.

“I don’t know why we’re not closer,” Carol would say. “The kids just don’t come around.”

“Our door is always open,” Tom pondered glumly. “But we don’t see them much.”

Although it was where their story would take them, the family’s beginnings weren’t in Texas. Thomas Eaton Lucas was born in Dunbar, West Virginia, and his hoarse, crusty voice, even in the waning years of middle age, would still betray those influences. He met Carol Maxine Morrison, a plainspoken Midwesterner, in her hometown of Port Huron, Michigan, when Tom was an assistant manager at a dime store, two doors from the dress shop where she worked as the credit manager. “There were lots of ten-cent stores in those days,” Tom remembers. “We had a counter, where folks came in for lunch.”

Carol’s boss, the dress store manager, introduced them, and before long Tom noticed Carol lingering outside the store. “Sometimes she’d watch me decorate the windows,” says Tom, a big, tall, dark-haired man with heavy jowls and a booming voice. “I guess it was about a year after we met that we started dating.”

“I liked to look at him,” admits Carol, a soft-spoken, round woman with deep-set eyes and thick, curly blond hair. “Sometimes I’d smile, and he’d smile back at me.”

At the time, Tom’s parents lived in Cambridge, Ohio. When Tom moved to be closer to them, he convinced Carol to follow. They married on July 22, 1962, and traveled through Ohio, settling in Martins Ferry, where Tom worked in a steel mill. The children arrived in a pack, first Brian, followed by Barry, and then Brent. Carol was pregnant a fourth time in five years when they learned some startling news about their second son, Barry. The four-year-old followed a ball into the street and never heard the school bus screech to a stop. It almost hit him. “Barry hadn’t talked much, but we didn’t think much of it. Brian talked for him,” Carol says. “We’d asked the doctor, but he said not to worry. When we had Barry tested, we found out he was deaf.”

Not much later, on December 30, 1968, a cold winter day, Carol went into labor. Tom loaded her into the family’s Volkswagen and bumped along the country roads to get to the hospital. “We were expecting another big old baby boy,” Tom says with a shrug. “After three sons, we’d given up on the idea of a daughter.”

They rushed into the emergency room, and Carol was ushered in quickly while Tom filled out the paperwork. Ten minutes later, before Carol had time to get out of her dress and into a hospital gown, their first baby girl was born, at eight pounds and one ounce. Through all three boys, Carol had the name Brenda picked out, just in case they had a daughter. Now she held Brenda Therese Lucas in her arms. Carol didn’t pay a lot of attention to the fact that the doctor continued to push on her abdomen and that the nurses hadn’t left the room.

In the days before routine ultrasounds, Carol didn’t know another surprise was in the offing. She’d never been told she carried twins. But eight minutes later, a second perfect, pink daughter entered the world, a bit smaller than her older sister, at six pounds, one ounce. Both infants were healthy.

“Here’s your number two,” the doctor said, holding up the baby.

“I was shocked,” Carol said. “Absolutely shocked.”

When the doctor came out to talk to the nervous father, he asked Tom, “What was it you wanted?”

“Well, Carol wanted a girl, but if it’s a boy, it’s okay with me,” he answered.

“Well, your wife got her wish,” the doctor said, and before Tom could get excited, the physician added, “And she got two of them!”

“I got weak in the knees and thought I was going down,” Tom says, with a laugh. “I threw my wide-brimmed hat in the air and I whooped and hollered.”

Carol had named the other four children, and when she held her final child in her arms, the proud mother came up with yet another “B” name, this one Belinda Tracie Lucas.

From the moment his parents brought his twin sisters home, Brian, who was five at the time, would remember being enthralled with them. He held them, especially Belinda, the smallest, helping to soothe the girls when they cried. He couldn’t say

Belinda

and struggled with

Tracie

, ending up calling the youngest sibling

Katie-do-do

. When she got older, Belinda would reference her position as the last born in the Lucas family lineup, and nickname herself Number Five.

With so many youngsters to care for, Carol became a stay-at-home mom. “She could have worked, but we put the emphasis on taking care of the kids,” Tom says. “That meant we didn’t have as much money as some families, but when our kids got home from school, their momma was always there.”

Delighted to finally have the daughters she’d longed for, Carol sewed matching dresses for her little girls. But the twins were fraternal, not identical, and before long the differences became apparent. The smaller at birth, Belinda, with her curly light brown hair, a wide smile, mischievous green eyes, and athletic build, quickly grew into the larger of the two. Meanwhile Brenda became a slightly built child, with straight dark brown hair. When it came to personalities, Brenda hung back, while Belinda overflowed with energy, often running ahead to open the door. Belinda wanted to be the first in every line. “No matter what was going on, Belinda was in the middle,” Brian says with a laugh. “She was a good kid, and she had spunk.”

Neither were girly girls—more of the tomboy variety who’d rather spend days climbing trees with their brothers than playing with dolls. Of the sisters, Belinda was the first to ride a bike. Once she learned, she taught Brenda. And before long Belinda began calling her older sister—albeit by eight minutes—“Shrimpie,” a nickname that has stayed with Brenda for life and always makes her smile. “Belinda taught Brenda how to tie her shoes,” remembers Carol. “Belinda was always kind of motherly, and if something needed to be taken care of, she was the one who’d do it.”

From those early years, Belinda was also protective. Of the Lucas children, it was Belinda who learned sign language, to communicate with Barry. While he read lips, he’d remember years later what that meant to him. If kids at school talked behind Barry’s back, making fun of his deafness, Belinda took them to task, even if the offenders were bigger than she. “Usually, Belinda would scare them off. I always went to her when I had a problem,” says Barry. “I always wanted Belinda’s opinion.”

It was the same when anyone gave Brenda a hard time; Belinda immediately stepped in to defend her more diminutive sister. And when they were at softball games, it was Belinda who took Brenda by the hand to the concession stand and gave the clerk her order. “Belinda never let anyone pick on me,” says Brenda. “She was always there for me. Always.”

Christmas was Belinda’s favorite holiday. That morning, she was habitually the first shaking the packages under the tree. Since the family opened gifts starting with the youngest, she was also the first to tear off the green and red wrapping paper to see what waited inside.

Those were good years, and looking back, Brian would say that “we were a regular family, your normal middle-class kind of family. And we had fun together.”

Sadly, before long, Brian would say that changed.

In the mid-seventies, Tom had an accident at the mill and an injury that led to a year’s rehabilitation. He and Carol thought about leaving Martins Ferry. The steel industry was hurting in response to imports, and many people were moving away. “I wanted a place where they’d have more opportunity,” he says. “Carol and I wanted to make things easier for the kids to get ahead.”

That year the family moved to Nacogdoches, the oldest town in Texas, a graceful place where the dogwoods and azaleas bloom in the early spring. Once the area was the hunting grounds of the Caddo Indians, and a local legend depicts a Caddo chief with twin sons. When they reached manhood, the wise old man sent his sons off to begin their own tribes. One went three days west, toward the setting sun, and founded Nacogdoches. The other traveled three days east, toward the rising sun, and founded its sister city, Natchitoches, the oldest settlement in Louisiana. The trade route connecting the two marked the eastern end of El Camino Real, also called the Old San Antonio Road.

On an undulating green landscape, Nacogdoches is a place where after a rain the air fills with the rich scent of the thick East Texas pine forests. People are friendly, brisket is slow-cooked over wood, and natives talk with a soft Texas drawl. For the Lucases, the city’s lure was family. Tom had a brother in the area and a sister three hours south in Houston. Later, Tom’s parents followed and settled nearby as well. In their new hometown, Tom opened a cultured marble business, selling sinks and countertops from a building on the outskirts of the city.

Later, Brian would say that the problems in the Lucas household kicked in about the time of the move to Texas. “When he got injured, our dad changed,” says Brian. “From that point on, it seemed like he was more demanding and we kids felt like Mom was always under his thumb.”

There was little doubt that Tom Lucas was a formidable figure, simply based on his physical size, booming voice, and his imposing manner. Belinda, too, would later tell friends that she saw her father as overwhelming and, at times, suffocating. She talked about the way he ruled the household.

Carol, however, would describe Tom as a good husband. And there’s little doubt that he was an involved dad. Tom and Carol believed in keeping their kids busy. For the girls that meant that by the time they hit junior high school, Belinda and Brenda were both active in Future Farmers of America and sports, baseball and basketball.

Of the two, Brenda was devoted to her animals. She raised chickens in the backyard of the family’s one-story home on a quiet street in town and worked with steers the Lucas kids kept outside Tom’s shop in the country. For Belinda, caring for the animals wasn’t fun but work. Still, she was conscientious, starting out every morning in the backyard chicken coop while still in her pajamas. At the Piney Woods Fair one year, Belinda’s broiler won grand champion, earning her $2,100, which she put away for college. The more outgoing of the sisters, Belinda showed Brenda’s steers. One year, while Brenda’s steer didn’t win, Belinda did, taking home the fair’s showmanship award.

Sports were to Belinda what FFA was to Brenda. While both girls played baseball and basketball, Belinda excelled. “Basketball was Belinda’s thing,” says Brenda. In junior high school Belinda was a cheerleader until her teacher told her she couldn’t do that and play on the team as well. At that point, Tom would later say, “Belinda decided to let the others cheer for her, and she stayed on the basketball team.”

Looking back, Belinda wasn’t a natural athlete. She wasn’t one who automatically jumped the highest or ran the fastest. For her, being able to perform took hard work. Summers were spent lifting weights, running and getting in shape for basketball season. “She was determined,” Tom says. “On the court, she didn’t hog the ball. She wanted to win, and she was part of the team. At times, if she couldn’t find girls to play with, she shot hoops with the boys.”

Because of her natural zeal, even after she left cheerleading, Belinda led the cheers at pep rallies. On the gym floor, she urged her fellow students to support the school’s teams and attend the games. Her fervor was contagious and, in the stands, Brenda shouted support for her twin sister. “Belinda was super-charged,” says a friend. “You couldn’t help but join in.”

“Everyone knew Belinda,” says another friend. “She was so in love with life, she just radiated happiness.”

At games, her chin-length dark blond hair flying, Belinda ran across the basketball court, as her parents and Brenda cheered. After practices, never one to fuss with her looks, while her mom drove, Belinda peeled off her basketball clothes and threw on her uniform to go to work at Burger King. At home, when she turned on the television, she more often than not put on a football or basketball game and sat at rapt attention, eyes focused on the game, diagnosing plays, until it was over.

At the same time, although she never lost that tomboyish bent, Belinda developed into a beautiful young woman. Nacogdoches is a college town, and Lynn Graves, the head football coach at Stephen F. Austin, the local university, lived just down the block from the Lucases. Belinda and Graves’s daughter were good friends, and the coach would remember watching Belinda mature. “She was the type of young lady who’d be shooting hoops with the boys one minute and walking down the street in high heels the next,” he says. “She was smart and funny, and she pretty much had everything going for her.”

Through high school, Belinda dated off and on. During one crush, she wrote “I Love” and the boy’s name all over the inside of her locker in permanent marker. By then, the eldest Lucas boy, Brian, was dating his future wife, Jill, a bright, friendly woman with short blond hair and large brown eyes. From the beginning, Jill was impressed by Belinda’s appetite for life, so startling compared to the usually reserved Lucas clan that Jill once asked Belinda, “Where did you come from?” Jill drove a Corvette, and at times, Belinda took over the driver’s seat, laughing as she floored it. After getting to know the two sisters, it never struck Jill as odd when she walked into the backyard and found Brenda wearing jeans and a T-shirt, while Belinda worked on her tan in a bikini.

As high school came to an end, Belinda talked about going into nursing, but before graduation, she changed her mind. “It was just natural that she’d want to be a teacher. I think she always knew she’d do something involving kids,” says Angie Luna, a girlhood friend. Luna had young twin sisters, and Belinda happily spent hours talking and playing with the girls. When Belinda babysat for her basketball coach, and he talked to her about what it was like to work with young athletes, Belinda’s plans took on more detail. “I don’t remember when, but at some point Belinda announced that she wanted to be a teacher and a coach,” says Luna. “And, with Barry in her family, I wasn’t surprised she’d decide to work with special-needs kids, the ones who needed the help the most.”