Kabbalah (6 page)

The teachings of the Zohar are presented within a framework of a sophisticated literary structure. It is a narrative of the experiences and spiritual adventures of a group of sages whose leaders are Rabbi Shimeon bar Yohai and his son, Rabbi Eleazar.

The other members are also early second-century sages. The literary framework was inspired by many stories scattered in talmudic and midrashic literature, which are integrated into a 31

K A B B A L A H

structured narrative that serves as a background for the sermons and the events described in the work. The Zohar is thus a pseudo-epigraphical work, which is not only attributed to an ancient sage but also creates an elaborate fictional narrative that supports most of the sermons included in it. The narrative includes descriptions of the group’s wanderings from place to place in the Holy Land, the sages’ meetings with wondrous celestial persons who reveal great secrets, and their visions of occurrences in the divine realm. The sections called “assemblies” (

idrot

) were probably modeled after a description of a gathering of mystics in the ancient Hekhalot Rabbati. The narrative includes a biography of Rabbi Shimeon, including a description of his last illness and death. Yet, the message of the Zohar is delivered in the classical, midrashic homiletical fashion, exegesis of verses in the Torah and other parts of scriptures in the elaborate hermeneutical methodology perfected by the ancient sermonists of the midrash. Many of the Zohar’s sermons are presented in a sophisticated, elegant way, making it one of the peaks of Jewish literary creativity in the Middle Ages.

The author of the Zohar put on, when writing this work, several layers of disguise, hiding his own personality, time, and language. He created an artificial language, an Aramaic that is not found in the same way anywhere else, innovating a vocabulary and grammatical forms. He attributed the work to ancient sages, and created a narrative that occurs in a distant place at another time. These disguises allowed him a freedom from contemporary restrictions. This is evident when the Zohar is compared to the Hebrew kabbalistic works of Rabbi Moses de Leon.

Often there are similar, or almost identical, paragraphs in the Zohar and the Hebrew works, yet the Zohar differs in the rich-ness, dynamism, and boldness of its metaphors, which are not found in the Hebrew texts. The radical mythological descriptions of the divine powers, the unhesitating use of detailed erotic language, and the visionary character of many sections—these are unequaled in Jewish literature, and place the Zohar among the most daring and radical works of religious literature and 32

T H E K A B B A L A H I N T H E M I D D L E A G E S

mysticism in any language. The paradox is that despite these radical elements Jewish readers could treat the Zohar as a conventional midrash. The use of traditional sages and old homiletical methodologies allowed the Zohar to be accepted as a traditional, authoritative work of Jewish religiosity.

This huge library includes every imaginable subject, yet at its center are two interwoven themes. The first theme includes “the secret of genesis” and “the secret of the

merkavah

,” that is, the detailed description of the emergence of the

sefirot

from the eternal, perfect, hidden divine realm and the emanation of the divine system that created and governs the world. This is a dynamic myth, unifying theogony, cosmogony, and cosmology into one whole myth. The second is the unification of this speculation concerning the divine world with traditional Jewish rituals, commandments, and ethical norms. Jewish religious practice was elaborately and meticulously connected with the characteristics and dynamic processes in the realm of the

sefirot

and the struggle against the

sitra ahra

, the powers of evil. In this way, the Zoharic worldview is based on the concept of reflection: everything is the reflection of everything else. The verses of scriptures reflect the emanation and structure of the divine world; as does the human body, in the anthropomorphic conception of the

sefirot

, and the human soul, which originates from the divine realm and in its various parts reflects the functions and dynamism of the

sefirot

. The universe reflects in its structure the divine realms, and events in it, in the past and in the present, parallel the mythological processes of the divine powers. The various sermons of the Zohar present these and other parallels in great detail. The structure of the temple in Jerusalem and the ancient rituals practiced in it are a reflection of all other processes, in the universe, in man, and within the heavenly realms. Historical events, the phases of human life, the rituals of the Jewish Sabbath, and the festivals are all integrated into this vast picture. Everything is a metaphor for everything else. In many sections the ultimate redemption, the messianic era, is included within these descriptions. All this is presented 33

K A B B A L A H

as a secret message, a heavenly revelation to ancient sages, using conventional, authoritative methodologies.

The Kabbalah in the Fourteenth and

The influence of the Zohar spread slowly in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but gradually its worldview came to dominate the scattered circles of kabbalists in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. However, the peak of creativity that was reached during the period in which the Zohar was composed was not maintained. The last generations of the Middle Ages saw the kabbalah spread in several rather isolated circles throughout the Jewish world, and only a handful of great kabbalistic works have reached us from this period. Some were written by well-known scholars, such as Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi, whose

Commentary on the Work of Genesis

and other work had meaningful influence. Others were pseudo-epigraphic, imitating to some extent the format of the Zohar, including the Sefer ha-Kanah, a commentary on the commandments attributed to the tradition of the ancient sage Rabbi Nehunia ben ha-Kanah, and Sefer ha-Peliah, probably by the same author, which includes an anthology of older kabbalistic texts. In Italy, the tradition of kabbalistic speculations that was started by Rabbi Menahem Recanatti was continued, and in central Europe many treatises that integrated the Spanish kabbalah with the traditions of the Hasidey Ashkenaz exerted meaningful influence. Rabbi Menahem Zioni’s commentary on the Torah and his treatise on the powers of evil represented Ashkenazi creativity in this field.

The messianic element in the kabbalah, presented by Rabbi Isaac ha-Cohen of Castile and developed in the Zohar, became prominent in the writings of kabbalists in Spain and elsewhere in the middle and second half of the fifteenth century. The increasing persecutions of Spanish Jewry in that century, culminating in the exile of the Jews from Spain in 1492, changed 34

T H E K A B B A L A H I N T H E M I D D L E A G E S

the spiritual atmosphere in the Jewish communities and caused the decline of the hitherto-dominant rationalistic philosophy and increased interest in the kabbalah. The sense of exile became central in the consciousness of Jewish intellectuals, and messianic speculations held an increasing place in Jewish religious culture. Several kabbalistic circles developed in this period of intense apocalyptic and messianic inclinations. One of the leaders, the Spanish kabbalist Rabbi Joseph dela Reina, became the hero of a well-known story, which described an attempt to overcome the Satanic powers and bring forth redemption by using kabbalistic and magical means. Another kabbalist, Rabbi Abraham berabi Eliezer ha-Levi, wrote a series of kabbalistic-apocalyptic treatises; he continued writing after the exile from Spain, when he settled in Jerusalem. This was the beginning of the process that, in the sixteenth century, transformed the kabbalah from the realm of scattered esoteric circles to the dominant spiritual doctrine of the Jewish people in early modern times.

35

K A B B A L A H

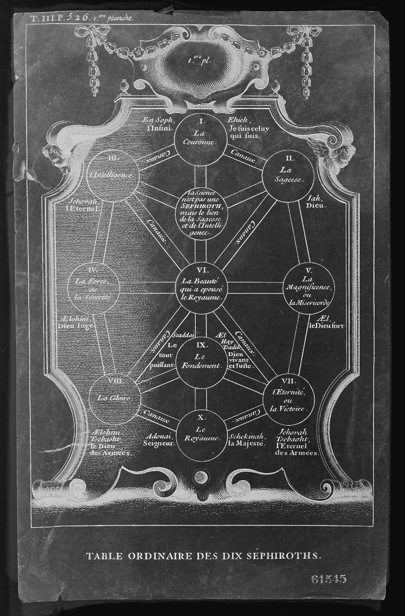

5 A Latin schematic drawing of the ten divine emanations, the

sefirot

, which together represent the power of God.

36

M A I N I D E A S O F T H E M E D I E V A L K A B B A L A H

4

Main Ideas of the

Medieval Kabbalah

The kabbalah in the Middle Ages inherited from ancient Jewish traditions a prohibition on discussing matters that relate to the divine world (

ma’aseh merkavah

), as well as a sizable body of descriptions and speculations concerning the nature and structure of that same realm. The result of this clash between the kabbalah’s interest in describing the divine world and the ancient ban was three-fold: first, the medieval kabbalists insisted on esotericism, keeping the kabbalah secret; second, they used pseudo-epigraphy, attributing their works to ancient figures, mainly

tanaim

, the sages of the Mishnah; and, third, they were traditionalists, who claimed that they were not revealing anything new, just copying or writing down traditions received from previous generations, either orally or in secret writings.

An additional precaution used by several kabbalistic writers was obscurantism and mystification, using hints and opaque references that cannot be understood by any “outside” reader who is not familiar with the particular terminology.

From a historical point of view, the main reason that the early kabbalists were not a focus of controversy and criticism for their radical new ideas was literary conservatism. The kabbalah is a new spiritual phenomenon that differed in a meaningful way from orthodox conceptions and worldviews. Yet, they expressed themselves in the most traditional literary forms, 37

K A B B A L A H

so that to an “outsider” their works looked like orthodox collections of ancient midrashim; or commentaries on biblical books, talmudic treatises, the prayers, or the ancient Sefer Yezira; or works of Jewish ethics (

sifrut musar

); or sermons and homiletic literature. Eight hundred years of intense and dynamic kabbalistic creativity did not produce a genre that can be called “kabbalistic literature.” There is no external distinc-tion between kabbalistic homiletic literature and nonkabbalistic works of the same genre. There is no way to determine whether a work employs the kabbalah or not by looking at its form and structure. In this way, with few exceptions, kabbalistic works blended into Jewish literary traditions.

The price the kabbalists had to pay for their successful blending in with traditional Jewish culture was the suppression of any expressions of individual spiritual and mystical experiences. A direct contact with the divine realm was not an acceptable part of Jewish culture in this period; it was regarded as a characteristic of the ancient past, when prophets and other people selected by God were allowed to experience divine revelation. In contemporary (that is, medieval and modern) religious experience God is met through the interpretation of the verses of ancient, scriptural revelation, or during the intense

kavanah

(the spiritual intention added to the traditional prayer texts) in prayer. Jewish culture of this period did not recognize, either theologically or in literary conventions, individual experiences of receiving information and instruction from God. A marginal exception was the practice of “questions from heaven,”

when some rabbis, mainly in the thirteenth century, indulged in presenting questions of law to God before going to sleep, and then interpreting their dream as a response to them. The kabbalists could not—assuming that they wished to do so— present their experiential spiritual world in direct writing. It is now the role of scholars to try to find traces of visionary and mystical experiences in the homiletic and exegetical writings of the medieval and modern writers. Very few kabbalists revealed in their writings the experiential basis of their specula-38

M A I N I D E A S O F T H E M E D I E V A L K A B B A L A H

tions; the best known among those who did in the Middle Ages was Abraham Abulafia. In later times, Rabbi Joseph Karo, Rabbi Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto, and others attributed their works to a celestial messenger, a

magid,

who was conceived as a supreme angel or a divine power

.

Yet these are a few exceptions in the vast kabbalistic literature, which in most cases is dressed in the form of impersonal exegetical and homiletic writing. In some cases, the reader may confidently discern a mystical experience hiding behind a homiletic presentation: some intense, visionary passages in the Zohar, for instance, indicate such experiential subtext rather clearly. Such an investigation, however, is obviously subjective in nature, and observations of this kind can never be proved in a methodological, systematic scholarly manner. In many cases, undoubtedly, Jewish mystics successfully disguised themselves as traditional commentators and preachers, preserving their loyalty to the presentation of the kabbalah as transmitted tradition rather than individual mystical experience.