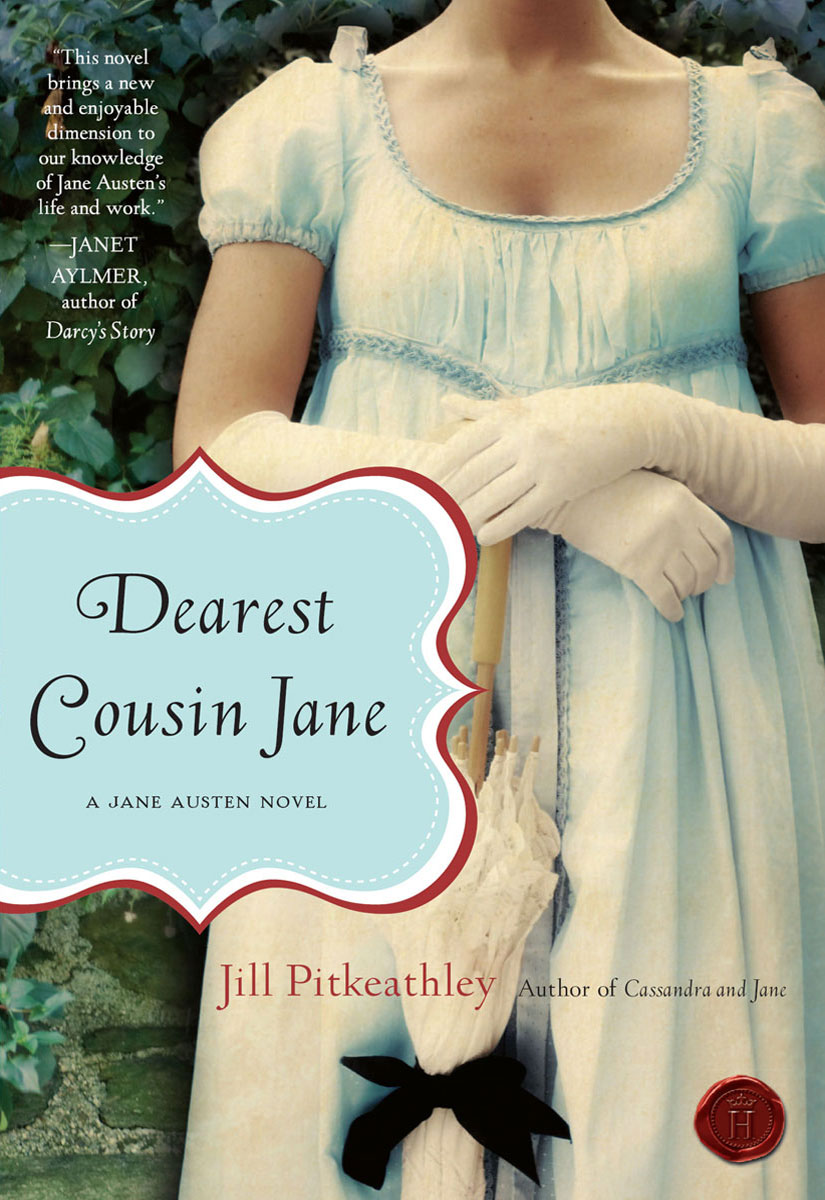

Dearest Cousin Jane

Read Dearest Cousin Jane Online

Authors: Jill Pitkeathley

A Jane Austen Novel

For my dear husband, David

Jane Austen at Steventon Rectory

Eliza Hancock

Philadelphia Austen Hancock Aboard the Madras Castle

Tysoe Saul Hancock

Eliza Hancock in Paris

Mrs George Austen at Steventon

Eliza de Feuillide

Eliza, Comtesse de la Feuillide

Jane Austen at Steventon Rectory

Philadelphia [Philly] Walter, Eliza and Jane’s cousin, Orchard Street, London

Eliza at Her House in Orchard Street, London

Cassandra Austen, Steventon

Eliza, Comtesse de Feuillide, at Steventon

Jane Austen, Steventon

Comte de Feuillide in La Bastille Prison

Letter from Henry Austen to His Sister Jane

James Austen at Deane parsonage

Philly Walter at Tunbridge Wells

Eliza de la Feuillide, London

Eliza Austen

The Reverend George Austen

Philadelphia [Philly] Walter, Tunbridge Wells

Letter from Henry Austen to Eliza Austen

Eliza at Her Residence in Dorking

Mary Austen [Mrs JA] at Deane Parsonage

Eliza in Upper Brook Street, London

Philly Walter at Tunbridge Wells

Mary Austen [Mrs JA] at Steventon

Eliza at Brompton

Henry Austen at Bath

Jane Austen at Brompton, London

Mrs Austen at Lyme

Philly Walter at Tunbridge Wells

Jane Austen at Bath

Henry Austen at Brompton, London

Philly Walter at Tunbridge Wells

Eliza at Brompton

Letter from Cassandra Austen to Eliza and Henry Austen

Mary Austen [Mrs JA ] at Steventon

Jane Austen, Sloane Street, London

Philly Walter Whitaker at Pembury, Kent

Eliza, Sloane Street, London

Henry Austen at Sloane Street

Jane Austen at Chawton

Jane and Henry Austen in Hampstead Cemetery

Henry Austen at Chawton Parsonage

Henry did marry Miss Jackson, who made him a loyal…

Jane Austen (1775–1817)

Reverend George Austen (1731–1805),

father of Jane

Cassandra Leigh Austen (1739–1827),

mother of Jane

James Austen (1765–1819),

brother of Jane

Mary Lloyd Austen (Mrs JA),

his wife

Edward Austen Knight (1767–1852),

brother of Jane

Elizabeth Bridges Austen Knight,

his wife

Henry Austen (1771–1850),

brother of Jane

Eliza Hancock de Feuillide Austen (1761–1813),

his wife

q.v.,

known as Betsy as a child and later as Mrs HA

Cassandra Austen (1773–1845),

sister of Jane

Francis (Frank) Austen (1774–1865),

brother of Jane

Mary Gibson Austen (Mrs FA),

his wife

Charles Austen (1779–1852),

brother of Jane

Frances (Fanny) Palmer Austen,

his wife

George Austen (1766–1838),

mentally handicapped brother of Jane

Philadelphia Austen Hancock (1730–1792),

sister of Reverend George Austen, mother of Eliza

Tysoe Saul Hancock (died 1775),

husband of above and father of Eliza

Jean Capot, Comte de Feuillide (executed 1794),

first husband of Eliza

Hastings de Feuillide (1786–1801),

son of Eliza and the Comte de Feuillide

Philadelphia (Philly) Walter Whitaker,

niece to Mrs George Austen and cousin to Jane and Eliza

Warren Hastings,

first governor-general of India, godfather of Eliza

I

have always found that the most effectual way of getting rid of temptation is to give way to it, so I shall accept both your offers,’ said Eliza as she glanced from one of my brothers to the other. Smiling at them both, she took the hands that each of them had held out to her and stepped down from the stage. ‘The wind is chill in here,’ she went on. ‘Now which of my two charming squires will fetch me my shawl?’

‘I will,’ they chorused eagerly, but while James waited for her to choose the messenger, Henry, younger and more agile, was already running down to the other end of the barn where the outdoor clothing was piled upon a chair. As he returned with the multicoloured shawl, a gift from Eliza’s godfather, I saw him glance triumphantly at James. Because Henry was my favourite brother, I was always on his side in these silly competitions that had developed between him and James for Eliza’s attention, but even I could see how she flirted outrageously with them both and played them off against each other. I had overheard my parents talking about it, too. They were not quarrelling, my parents never did that, but they were certainly disagreeing about Eliza and the way two of their sons were reacting to her.

‘’Tis nothing but harmless fun my dear,’ said my father. ‘After all, she is a married woman with a small child so can have no serious designs on them.’

‘Mr Austen,’ replied my mother, ‘you may be a clergyman well versed in the sins of your parishioners, but you are innocent of the wily ways of a woman like her. Why, she has been headstrong and spoiled since the time we first knew her and that racketing life she has led in France has not made her conform to our simple country ways. I tell you both James and Henry are in a fair way to having their heads turned and it is not a good example either to our girls. Cassandra is almost fifteen now and we must think of these things.’

‘But Cassandra is as innocent as her father,’ he replied, ‘and not one to think ill of anyone.’

‘What about Jane then?’ my mother persisted. ‘I can see that she is fascinated by Betsy, and you know how easily impressed she is by anything out of the common way.’

My mother had never quite become used to the idea of the niece she had always known as Betsy being called Eliza, as she suddenly announced she wished to be known when she was fifteen years old, and found it even more difficult to refer to her as Madame la Comtesse, as she should rightfully be known since she became the wife of the Comte de Feuillide three years ago.

‘Jane listens to everything Betsy says and takes it all in. Why only yesterday I overheard both girls being told how the Comte adores her and would never think of taking a mistress as most French counts do. I ask you, Mr Austen—is that suitable talk for a child of twelve?’

‘If you are worried,’ said my father, ‘have a word with my sister. I am sure that Philla will reassure you that it is just Eliza’s way and there is nothing to worry about. As far as I can see, both the boys are enjoying the acting scheme, and James’s writing talents are being encouraged after all. Now that he is back from France and going up to Oxford, the parsonage might seem a little dull to him without our acting plans. After all, my dear, it is Christmas and we should

all be enjoying ourselves. Look how we all enjoyed Eliza’s playing last night.’

‘Come Mr Austen, did I not arrange the hiring of the instrument especially for her? And you know I am the first to encourage the acting, but I do not want to risk encouraging anything else.’ Glancing up and seeing that I was nearby and might be overhearing, she closed the conversation with a meaningful look at my father, telling him, ‘I am sure you know just what I mean.’

Henry, fresh from his triumph with the shawl, was eager to begin rehearsals again, but Eliza told him that she must now spend some time with her son, little Hastings, and could rehearse no more until he was abed.

‘Mama and your sister have watched him all day you know, and it must now be his mama’s turn.’ Her dark, wide-set eyes held his fascinated gaze.

‘But dear cousin,’ said James, ‘you know that both my sisters are only too delighted to care for him, even if Aunt Philla needs to rest.’

I was out of humour that he should volunteer my services without asking me. I was, in fact, rather nervous about taking care of little Hastings because of his peculiar condition. No one mentioned it, but it was clear he did not thrive. He could scarcely walk and, though Eliza made light of it, I had heard my mother whisper that he reminded her of my brother George, who was similarly stricken and could not live a normal life at home with us but had to be boarded out at Monk Sherborne. As Cassandra and I had been away at school in Reading, I had not been to visit him at Monk Sherborne recently, but I knew my parents went regularly. We had first seen Hastings last Christmas when Eliza and Aunt Philla brought him to stay; his father, the Comte, was engaged with his estates in France. James was not at home on that occasion

as he was with the Comte in France. Eliza had invited him for a visit there. Our family could not afford a grand tour such as many young men undertook before Oxford, but my parents thought a visit to France might be a substitute. The result was that Henry had had all Eliza’s attention that year and, although but fifteen at the time, had been her escort and played quite the gentleman to her in their first tries at acting. His nose was quite put out of joint that James, older and taller and an Oxford man, was now competing for her attentions. He was writing some of the scripts, too, so Eliza gave him a good deal of attention in return, diligently asking him how he wanted this line or that spoken. It was really amusing and gave Cassy and me some fun to watch them making fools of themselves.

‘She is a married woman,’ we repeated to each other in our bedroom, ‘she can have no serious intent.’

I liked the idea of two men fighting over me, but Cassandra was as ever sensible and serious.

‘No, Jane, she is improper and our brothers are ridiculous. Have you read the piece that James has written and Eliza is to act tomorrow?’

‘Oh yes, and I think it very fine.’

‘Fine? When it refers to women being superior and no longer in second place?’

‘But Cassy, why should we be in second place? Eliza does not seem to take second place to anyone. She has plenty of money as far as I can see, a husband who adores her, and yet she is free to go about as she pleases. Do you not envy her?’ But I knew what my dear sister’s response would be before she said it.

‘No, I envy no one. I am content.’

The next day Eliza read James’s piece and both he and Henry watched her, fascinated.

Her dark curls hung about her face as she read and her voice, the tone always low for a woman’s, became deeper and softer as she read.

But thank our happier stars, those times are o’er

And woman holds a second place no more

Now forced to quit their long held usurpation

These Men all wise, these ‘Lords of Creation’,

To our superior sway themselves submit,

Slaves to our charms and vassals to our wit;

We can with ease their ev’ry sense beguile

And melt their resolution with a smile…

My aunt Philla sat nursing little Hastings and smiled encouragingly at James.

‘Bravo James—we shall have a writer in the family yet.’

I could see that my mother, who also sat watching, was displeased by this remark. Though she liked to have James, always her favourite of her six sons, praised, she felt that her own skill with words should be acknowledged by her sister-in-law. I tried to make amends:

‘He has doubtless inherited Mama’s talents—you know how she is always dashing off rhymes and riddles for us and for the boarders.’

As ever, I could not manage to please her.

‘What nonsense, Jane. James has a fine talent and shows it in this script.’

‘But surely it is the way the lines are spoken that shows them off to advantage,’ put in Henry, gazing at Eliza. ‘Our neighbours will be in raptures when they hear us the day after tomorrow.’

‘Who are we expecting?’ asked my aunt, trying perhaps to avert any more strife between her nephews.

‘Oh the Biggs and the Lloyds, of course, and perhaps even Tom Chute if he does not consider himself too grand now that his papa sits at Westminster. James was hunting with him yesterday and invited him I believe.’ My mother got up. ‘Come, sister, we must attend to our household affairs and leave these young people to their rehearsals—it grows cold in this barn and will do that little boy no good.’

I think it must have been Eliza who suggested the theatricals the previous year when she visited us at Christmas. We would not have taken much persuading—we were ever a family for readings and scenes. But through Eliza we grew more adventurous and soon the large barn was fitted up with a proper stage and we began to collect many a costume and piece of scenery, side wings and backdrops, too. It was most amusing and though the presence of Eliza added spice to it and she always had the best parts, we all participated and enjoyed it. As well as our neighbours, we had been expecting our cousin Philly Walter to join us that year, but in the end she did not. I overheard my mother and aunt discussing it.

‘Eliza is most disappointed that Philly has after all decided to stay in Tunbridge Wells for the festive season,’ said my aunt. ‘Eliza is very fond of her, you know, and did so wish she might join us.’

‘Well for my part,’ said my mother, ‘I prefer her to stay away rather than be with us only to disapprove.’

‘Disapprove—would she?’

‘My dear, Philly and her mother disapprove of everything—from the way I bring up my family to the number of times we have beef on our table.’

‘Really? She and Eliza seem to get along tolerably well.’

‘That may be because Eliza is too forgiving and does not realise that Philly will judge her most severely for what she sees as frivolous behaviour.’

‘I hope, sister, that you are not suggesting my Eliza behaves frivolously?’

‘Why no, but in her last letter to Mr Austen, Philly was wondering that Eliza does not join her husband in France. And even you, my dear, must own that the Comte ought to have had sight of his only child before this—he is near two years old and has never seen his papa.’

‘We intend to return to France in the spring as you know, but things are so unsettled there at present.’

‘Sister, it is not I who makes the criticism but that minx Philly. Betsy—pardon me, I mean Eliza, of course—would do well to be wary of her.’

Philly was not a person who found favour in my eyes either—especially as I know she had described me ill the last time we had met when we all travelled to Kent. She said I was whimsical and affected and, though I laughed with Cass about it, I found the judgement hurtful.

But I knew, too, that both Eliza and my aunt should be wary of Philly’s opinions because she seemed to believe there was something very shocking in Aunt Philla’s background. I had heard this referred to once or twice, but whenever I approached the subject was changed. Cass and I often speculated about what it was. We knew she had travelled to India as an unmarried girl and had met Uncle Hancock there very shortly before marrying him.

‘Do you think it could be that Cass?’ I asked her one night

‘I think it makes her very brave to travel alone and so far, but I cannot see that it is shocking.’

I could not either and longed to know the truth, but of course it was not a subject we could raise before Eliza and my mother would have been very angry had she known we discussed such matters. She came upon us once, Cassandra and me, with Eliza, discussing her husband.

I was asking if she loved him very much, as I thought it very romantic to have a French Comte for a husband.

‘Why no, I do not love him, but he provides me with a comfortable means of living and he adores me, which is, you know, the most important thing. It is a bargain one makes: I perform my conjugal duties and he provides me with an agreeable way of life.’

‘Eliza,’ said my mother, coming into the room in a great hurry, ‘you forget yourself. These are innocent young girls and you are under my roof. You will kindly remember that in future.’

I do not know if it was this conversation that caused the prompt departure of my aunt and cousins. Of course, there was the excuse that my father’s pupils would soon be returning to school and we would be short of space, but I could sense Mama’s relief when they departed, in a hired carriage with their mountains of trunks and bags.

‘Next time we come, dear aunt,’ said Eliza, kissing my mother on both cheeks, à la française, ‘I do hope it will be in our own carriage. It is

so

inconvenient to have to hire a chaise and four.’

As our family had never owned a carriage, I could see that this remark was not very tactful, but my mother merely smiled and said to her sister-in-law: ‘Come again as soon as you might and take care of the dear child when you travel to France.’

I do not think she meant Eliza.

I am not sure who told us that Eliza was an heiress, but I think it might have been when our brother Edward visited Cassandra and me when we were away at the Abbey School. Our cousin Jane was there, too—how confusing it is to have so many in our extensive family sharing so few names. Edward and Jane’s brother—also called Edward, but we always called him Ned—came to see us and to our great delight we were allowed to go into Reading with them. We took our dinner at an inn in town and while we were there I remember telling my brother about a novel I was reading in which

an heiress was cheated out of all her possessions by an unscrupulous uncle.

‘Why, it is good fortune then for our own family heiress that our father has the guidance of her fortune—he is, I think, unlikely to cheat her. In fact, I can see him being too indulgent with her and letting her have any monies she begs for,’ said my brother.

‘And anyway,’ joined in Ned, ‘if it were to be spent, there would surely be more coming from her benefactor eh? I hear Warren Hastings is worth a pretty penny.’