Kabbalah (8 page)

The feminine power in the divine world, best known by the name

shekhinah

(divine residence) is one of the most prominent concepts that distinguishes the kabbalah from other Jewish worldviews, and it had a significant impact in shaping the kabbalistic theory and practice. In kabbalistic literature she is designated by many scores, if not hundreds, of names and titles, and numerous biblical verses have been interpreted as relating to her. The employs of the

shekhinah

are described in great detail in the Zohar, and coming into spiritual contact with her is a main component of kabbalistic rituals. She is the tenth and lowest power in the divine realm, and therefore closest to the 45

K A B B A L A H

material, created world and to human beings. She is the divine power that is envisioned by the prophets, and after their death the righteous reside in her realm. As the lowest

sefirah

she is closest to the sufferings of the people of Israel, and is most exposed to the machinations of the evil powers, who constantly try to establish dominion over her. Being feminine, she is the weakest among the divine powers, and the satanic forces can achieve a hold and draw her away from her husband (the male divine figure, often the totality of the other nine

sefirot,

or, sometimes specifically the sixth

sefirah, tiferet),

thus disrupting the harmony of the divine world. She is dependent on divine light, which flows from above; she is like the moon, which does not have light of its own, only the reflection of the sun’s light. The redemption of the

shekhinah

from her exile and suffering and reuniting her with her husband is the main purpose of many kabbalistic rituals.

Unlike many other phenomena that characterize the kabbalah, the history of the

shekhinah

is rather well known.

Scholars agree about the development of this concept, although they have different views about the source of its conception as a feminine power. The term “

shekhinah”

is not found in the Bible, and it was formulated in talmudic literature from the biblical verb designating the residence (

shkn

) of God in the temple in Jerusalem and among the Jewish people. “

Shekhinah

” is used in rabbinic literature as one of the many abstract titles or references to God, which replaced in their language the proper names of God used in the Bible. Like “the Holy one Blessed Be He” (

ha-kadosh baruch hu

), “heaven” (

shamayim

), “the name”

(

ha-shem

), “the place” (

ha-makom

), and others, it has been used to designate God without naming him, and the terms are in-terchangeable. Indeed, there are talmudic-midrashic statements that in one place use

shekhinah

and, in another, one of the similar phrases. It did retain some particular flavor of the divine power residing within Jerusalem and the people of Israel, but was always one of the synonyms used to designate God.

Though the word “

shekhinah”

in Hebrew is grammatically a 46

M A I N I D E A S O F T H E M E D I E V A L K A B B A L A H

feminine one, there is no indication in ancient literature of any particular feminine characteristics that separate the

shekhinah

from other appellations of God.

A change occurred in the early centuries of the Middle Ages.

Some late midrashic compilations use the term “

shekhinah”

to designate an entity that is separate from God himself. Rav Saadia Gaon, the great leader of the Jews in Babylonia, made a clear, theological statement to this effect in the first half of the tenth century. In his philosophical work, “Beliefs and Ideas,” written in Arabic around 930 CE, which is the first comprehensive, systematic Jewish rationalistic theology, he used the term “

shekhinah”

to overcome the difficult problem of the anthropomorphic descriptions of God in scriptures. As a rationalist, Saadia could not accept physical references to the infinite, perfect God, so he postulated that all such references relate not to God himself but to a created angel, supreme and brilliant but still a creature, which is called

kavod

(glory, honor) in the Bible and

shekhinah

by the rabbis. Since Saadia, therefore, the

shekhinah

is conceived in Jewish writings as a lower power, separate from God, which has its main function in the process of revelation to the prophets. It can assume physical characteristics, and it can be envisioned by human eyes.

The next stage in the development of the concept of the

shekhinah

occurred in the works of eleventh-and twelfth-century commentators, philosophers, and theologians, who were reluctant to accept that the descriptions of God by the ancient prophets are actually references to a created angel. Several of them, the most prominent was Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra in the middle of the twelfth century, described the

kavod-shekhinah

as an emanated divine power, which can assume characteristics that allow revelation and anthropomorphic descriptions. This concept was used by the esoterics and pietists of the Rhineland and other writers. By the late twelfth century the

shekhinah

was conceived as a separate, emanated divine power that is revealed to the prophets and assumes other worldly functions. In all these sources there is no hint of this entity being feminine.

47

K A B B A L A H

The Book Bahir, the first work of the kabbalah, is the earliest source we have that might imagine the

shekhinah

as a feminine power. The author used ibn Ezra’s concepts of the identity of the

shekhinah

and the

kavod

as a separate, emanated power, but in several sections, especially in the context of parables, he refers to this power in feminine terms. She is described as wife, bride, and daughter of the masculine power. There is very little in the Bahir in this context that is clearly erotic, but subsequent kabbalists understood its sometimes cryptic references as indicating the presence of a feminine divine power in the realm of the

sefirot

. Thirteenth-century kabbalists in Gerona and Castile, as well as Abraham Abulafia, accepted this image, though they developed it in a minimal, restrained manner. The Zohar, and other kabbalistic works from the end of the thirteenth century and the beginning of the fourteenth, made the myth of the feminine

shekhinah

a central element in their descriptions of the divine world, made her the purpose of rituals and religious experiences, and established this as one of the most prominent components of the kabbalistic worldview.

Gershom Scholem regarded the concept of the feminine

shekhinah

in the Book Bahir as the appearance of a gnostic concept within the early kabbalah. It could be regarded as an ancient Jewish gnostic concept that surfaced in the kabbalah in the Middle Ages after being transmitted in secret for many centuries, or the result of the influence of Christian Gnosticism, which emphasized the role of feminine powers in the divine world. Many scholars accepted Scholem’s explanation, and saw the image of an androgynous, gender-dualistic divine world as the result of gnostic impact. Recently, however, several scholars have presented a different approach: The femininity of the

shekhinah

is the result of the influence of the intense Christian worship of the Madonna, the Mother of Christ, that peaked in the twelfth century. This occurred, according to them, in Provence or northern Spain in the late twelfth century, and therefore it does not indicate an ancient Jewish gnostic con-48

M A I N I D E A S O F T H E M E D I E V A L K A B B A L A H

cept. This explanation may reflect the recent decline in the belief that there was a gnostic “third religion” that greatly influenced both Judaism and Christianity. There is no definite proof of that or any detail or phrase that indicates the impact of the Christian concept of the Virgin Mary on early kabbalistic terminology and ideas.

The third possibility is to assume, in the absence of definite proof to the contrary, that the femininity of the

shekhinah

results from the individual inspiration of the Bahir’s author. This can be understood from a literary point of view as the result of his frequent, almost obsessive, use of parables of kings and queens, princes and princesses, as well as a unique mystical experience.

From a methodological point of view, it is always better to assume the minimal conclusion attested by the texts until another one can be presented with adequate documentation.

“The Emanations on the Left”

Rabbinic tradition, represented by talmudic-midrashic literature, is remarkably ignorant of the existence of independent powers of evil that struggle against divine goodness and create a dualistic state of affairs in creation. Satan in his various manifestations in this literature is a power within the divine court and God’s system of justice. The esoteric and mystical treatises of the ancient period, the Hekhalot and Merkavah literature, did not present an intensified image of the powers of evil. In the apocryphal and pseudo-epigrahical literature of antiquity, as well as in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the literature of early Christianity, we do find some more pronounced tendencies toward dualism of good and evil, but most of these texts were not known to Medieval Jewish thinkers. The first indication of a satanic rebellion against God in rabbinic literature is found in the eighth-century midrash

Pirkey de-Rabbi Eliezer,

but this seemed to have little impact until the twelfth century. The section of this midrash in which the rebellion is described was included in the Book Bahir, serving as its concluding chapter.

49

K A B B A L A H

The formulation of the powers of evil as an independent enemy of the divine, and the description of human life as being conducted in a dualistic universe in which evil and good are in constant struggle, is the contribution of the kabbalah to Jewish worldview. There are some indications of an intensified conception of evil in the Book Bahir and in the works of the early kabbalists in Provence, but the first kabbalistic dualistic system was presented in a brief treatise written by Rabbi Isaac ben Jacob ha-Cohen, entitled

Treatise on the Emanations on the Left

.

This treatise, written in Castile about 1265, describes a parallel system of seven divine evil powers, the first of which is called Samael and the seventh, feminine one is called Lilith. While both of these figures have a long history in Jewish writings before Rabbi Isaac, it seems that he was the first to bring them together and present them as a divine couple, parallel to God and the

shekhinah

, who rule over a diverse structure of evil demons, who struggle for dominion in the universe against the powers of goodness, the emanations on the right. It should be remembered that “left” (

smol

) and Samael are almost homonyms in Hebrew. Rabbi Isaac was the first to present a hierarchy of evil powers and evil phenomena, including illnesses and pesti-lence, connecting all of them into one system.

Rabbi Isaac presented a mythological description of the relationship between the satanic powers; he described the “older Lilith” and “younger Lilith,” the latter being the spouse of Asmodeus, whom Samael covets. The realm of evil includes images of dragons and snakes and other threatening monsters.

He claimed to have used various ancient sources and traditions, but it seems that they are fictional ones, invented by him to give an aura of authority to his novel worldview. He used older sources, including the writings of Rabbi Eleazar of Worms, but changed their meaning and inserted his dualistic views into them.

Rabbi Isaac did not assign a religious role to human beings in the process of the struggle against evil. Unlike Rabbi Ezra of Girona, he did not find the root of evil’s existence in the events in the Garden of Eden and human sin. Evil evolved from the 50

M A I N I D E A S O F T H E M E D I E V A L K A B B A L A H

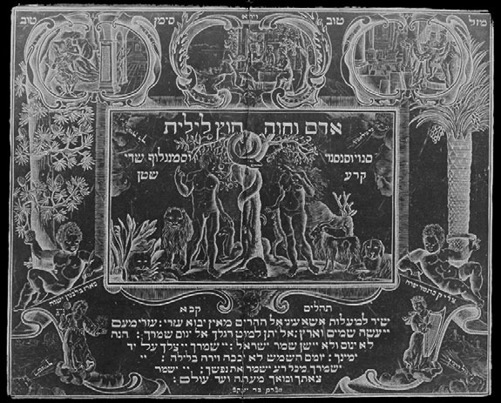

6 An amulet designed to repel the power of Lilith.

51

K A B B A L A H

third

sefirah

,

binah,

as a distorted side effect of the process of emanation. It continues throughout the history of the world, and will come to an end in the final, apocalyptic struggle between Samael and the messiah. The last pages of this treatise are dedicated to a detailed description of the final battles between angels and demons, and the ultimate triumph of the messiah. Thus, this treatise is the first presentation of a dualistic concept of the cosmos in kabbalistic literature, and at the same time it is the first to describe messianic redemption in terms of the kabbalistic worldview. Earlier kabbalists hardly paid any attention to the subjects of messianism and redemption; only in Rabbi Isaac’s treatise do we find the first integra-tion of kabbalah and messianism, a phenomenon that later became central to the kabbalah and a main characteristic of its teachings.