Kabbalah (10 page)

M A I N I D E A S O F T H E M E D I E V A L K A B B A L A H

herence to the instruments supplied by God in the Torah for this purpose. These systems prohibit any change or deviation from the traditional modes of religious adherence, because the commandments, being divinely devised instruments for the achievement of divine goals, cannot be tempered by the logic or inclinations of human beings. The most minute deviation from the halakhah immediately and automatically constitutes a transgression, thus inevitably strengthening the powers of evil and delaying the completion of the

tikkun

. The kabbalists thus presented a radical new mythology, which drastically spiritualized Jewish religious culture, but at the same time they enhanced and invigorated the traditional Jewish way of life, giving it powerful new spiritual incentives.

Spiritualization did not mean departing from the physical, but rather reinterpreting the spiritual and giving the mundane, daily rituals a magnificent, new dimension of meaning.

Adherence to the kabbalistic conceptions became synonymous in Jewish history to strict orthodoxy. The first thing that nineteenth-century reformers of Judaism did, before they began to modernize and change the halakhah and the prayer-book, was to rid themselves of any trace of reverence or regard for the teachings of the kabbalah. They understood that the kabbalah cannot be separated from the strict traditional observance of the totality of the commandments. Until the middle of the twentieth century, the Jewish denominations of reformed, conservative, reconstructionist, and modern orthodox were characterized by their rejection of any interest in the kabbalah.

The rabbinic Jewish academic institutions in the United States did not accept, until very recently, the kabbalah as a legitimate aspect of Jewish culture, while secular academic institutions in the United States, Israel, and Europe did not have any such hesitations.

59

K A B B A L A H

7 The

Kabbalah Denudata

was an extensive anthology of kabbalistic works for the Christian world.

60

M O D E R N T I M E S I : T H E C H R I S T I A N K A B B A L A H

5

Modern Times I:

The Christian Kabbalah

The kabbalah was transformed from a uniquely Jewish religious tradition into a European concept, integrated with Christian theology, philosophy, science, and magic, at the end of the fifteenth century. From that time to the present it has continued its dual existence as a Jewish phenomenon on the one hand and as a component of European culture on the other hand.

The failure to distinguish between the two different—actually, radically different—meanings of the kabbalah in the intrinsic Jewish context and in the European-Christian context is a key reason for the confusion surrounding the term and concept of the kabbalah today. Readers are disappointed when they do not find the characteristics of the Jewish kabbalah in the writings of Christian kabbalists, and vice versa. The confusion is increased by the fact that there is no unanimity in the usage of the term either within Judaism or outside of it, so that various, different and conflicting conceptions of what the kabbalah is prevail in both cultures. The following paragraphs are not intended to explain what the kabbalah—or even the Christian kabbalah—“really” is. They constitute an attempt to present the main outlines of the development of the different meanings and attitudes that contributed to the multiple faces of the kabbalah in European (and, later, American) Christian culture.

61

K A B B A L A H

The development of the Christian kabbalah began in the school of Marsilio Ficino in Florence, in the second half of the fifteenth century. It was the peak of the Italian Renaissance, when Florence was governed by the Medici family, who supported and encouraged philosophy, science, and art. Florence was a gathering place for many of the greatest minds of Europe, among them refugees from Constantinople, which was conquered by the Turks in 1453. Ficino is best known for his translations of Plato’s writings from Greek to Latin, but of much importance was his translation to Latin of the corpus of esoteric, mysterious old treatises known as the Hermetica. These works, probably originating from Egypt in late antiquity, are attributed to a mysterious ancient philosopher, Hermes Trismegestus (The Thrice-Great Hermes), and they deal with magic, astrology, and esoteric theology. Ficino and his followers found in these and other works a new source for innovative speculations, which centered around the concept of magic as an ancient scientific doctrine, the source of all religious and natural truth.

A great thinker who emerged from this school was Count Giovani Pico dela Mirandola, a young scholar and theologian, who died at age thirty-three in 1496.Pico took a keen interest in the Hebrew language, and had Jewish scholars as friends and teachers. He began to study the kabbalah both in Hebrew and in translations to Latin made for him by a Jewish convert to Christianity, Flavius Mithredates. His best-known work, the “Nine Hundred Theses,” included numerous theses that were based on the kabbalah, and he famously proclaimed that Christianity’s truth is best demonstrated by the disciplines of magic and kabbalah. Modern scholars have found it difficult to distinguish in Pico’s works between these two: magic is often presented as a synonym for the kabbalah. Pico regarded magic as a science, both in the natural and theological realms, and he interpreted the kabbalistic texts with which he was familiar as ancient esoteric lore, conserved by the Jews, at the heart of 62

M O D E R N T I M E S I : T H E C H R I S T I A N K A B B A L A H

which was the Christian message, which is fortified by the study of kabbalah.

Pico’s work was continued by his disciple, the German philosopher and linguist Johannes Reuchlin, who lived from 1455 to 1522. Reuchlin acquired an impressive knowledge of Hebrew and of kabbalistic texts, which was expressed in numerous works, but mainly in his

De Arte kabbalistica

(1516), which became the textbook on the subject for two centuries.

This work presents, in three parts, the philosophical, theological, and scientific discussions of three scholars, a Christian, a Muslim, and a Jew. The Jewish scholar is named Simon, and he is introduced as a descendant of the family of Rabbi Shimeon bar Yohai, the central figure in the narratives of the Zohar.

Simon presents the principles of the kabbalah (as Reuchlin saw them), and his Christian and Muslim colleagues integrate them with general principles of philosophy—represented mainly by what they believed to be Pythagorean philosophy—and those of science and magic. Reuchlin’s presentation was regarded by his own disciples and by followers throughout Europe as a definitive, authoritative presentation of the kabbalah.

“Kabbalah” in the writings of Pico and Reuchlin is radically different from the medieval Jewish kabbalah that they used as their source. They included in this term all postbiblical Jewish works, including the Talmud and midrash, the medieval rationalistic philosophers including Maimonides, and the writings of many Jewish exegetes of the Bible, most of them having no relationship to the kabbalah. The Jewish esoteric texts that they read, in the original or in translation, included many nonkabbalistic ones, including those of the Hasidey Ashkenaz (the medieval Jewish pietist) or of Abraham Abulafia, which were not typical of the mainstream of Jewish kabbalah. The Zohar was used very seldom, and the references to it were often derived from quotations in other works. The image of “kabbalah” as it emerges from the works of early Christian kabbalists is thus meaningfully different from the one presented by the Hebrew sources.

63

K A B B A L A H

Most meaningful are the differences in the subjects that are discussed. The intense kabbalistic contemplation of the “secret of creation” and the emergence of the system of the

sefirot

from the infinite Godhead is rather marginal in the deliberations of the Christian scholars; they had ready the theology of the Trinity, which they integrated with their understanding of the kabbalah. The

shekhinah

as a feminine power was of little interest, as well as the erotic metaphorical portrayal of the relationships in the divine world. The dualism of good and evil in the Zoharic kabbalah was not a main subject, nor was the theurgic element and the impact of the performance of the commandments on celestial processes. Mystical experiences, visions, and spiritual elevations were not at the center of their interest; they regarded themselves as scholars, scientists, and philosophers rather than mystics.

The Christian kabbalists were most impressed by the Jewish nonsemantic treatment of language, for which they had no Christian counterpart. The various names of God and the celestial powers were for them a new revelation. The various trans-mutations of the Hebrew alphabet, as well as the numerological methodologies, which are essentially midrashic rather than kabbalistic, became the center of their speculations. The Hebrew concept of language as an expression of infinite divine wisdom contrasted with the intensely semantic Christian attitude toward scriptures, which was the result of their being translations, and this disparity is essential to the understanding of the Christian kabbalists. In many cases, like that of “numerology,” it was the methodologies of the midrash that became the core of their understanding of the ”kabbalah.” The freedom of speculation and the ease with which new meanings can be attributed to ancient texts in this context were their main concerns. A prominent example of the identification of the kabbalah with magic and numerology was presented in the popular, influential work

De Occulta Philosophia

(1531), by Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim, who was secretary to the Emperor Charles V.

64

M O D E R N T I M E S I : T H E C H R I S T I A N K A B B A L A H

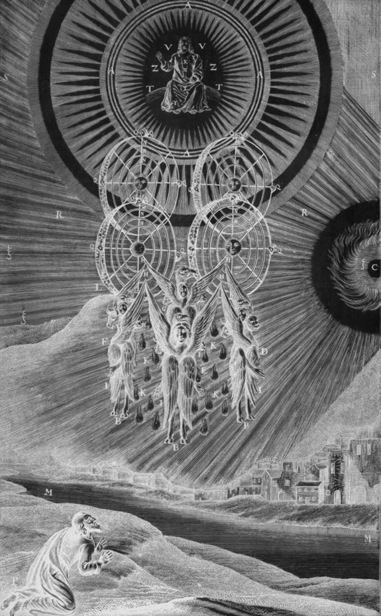

8 Henry More’s

Vision of Ezekiel

. Many thinkers in the Cambridge school of neo-Platonists such as Henry More studied the kabbalah.

65

K A B B A L A H

The meeting with the Jewish conception of divine language enabled the Christian kabbalists to adopt the belief in the ability of language—especially names, and in particular divine names—to influence reality. This gave the sanction of ancient authority to the Renaissance scholars’ belief in magic as a dominant power in the universe. What was commonplace in Judaism (and was not conceived of as magic) became prominent in the Christian kabbalists’ worldview. This was easily combined with the other major conception that these scholars derived from the Jewish sources—

harmonia mundi

. This image of the parallel strata that create structural harmony in the cosmos, nature, and human beings derived from the Sefer Yezira, which in the kabbalah was extended to the divine realm, was thus integrated into European philosophy and science. One of the most important expressions of this is found in the works of the Ve-netian scholar Francesco Giorgio (1460–1541), especially in his well-known

De Harmonia Mundi

(1525). The Hebrew works were not the only, nor even the major, source of this Christian concept of

hamonia mundi

; the relationships between microcosmos and macrocosmos, and between man and the Creator in whose image he was created, were developed in various schools of neo-Platonists during the Middle Ages. Yet in the schools of Pico, Reuchlin, and their successors they were often described as elements of the kabbalah, the ancient Jewish tradition that Moses received on Mount Sinai.

Among the famous thinkers of the sixteenth century who made the kabbalah a major subject of their studies was Guillaume Postel of Paris (1510–1581), who was the first to publish the Sefer Yezira with a Latin translation and a commentary; he also translated several sections from the Zohar.

Lurianic kabbalah was first presented to the Christian world in an extensive anthology of kabbalistic works,

Kabbala Denudata

(1677–1684) compiled by Christian Knorr von Rosenroth. The works of the great seventeenth-century German mystic Jacob Boehme were interpreted by his followers as reflecting 66