Insectopedia (10 page)

With the rise of behaviorism in the 1920s, instinct fell out of favor as an explanation of animal behavior and reemerged only in the 1950s with the popularization of the ethologists, especially Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen, who, though Darwinians, enforced a sharp division between instinct and learning. There is a line here that reaches across the decades from Fabre to these more recent students of animal behavior and is held together by simple behavioral experiments in natural settings, by close observation, and by the familiar combination of science and wonder. It’s a line that somehow bypasses Fabre’s hostility to evolution and instead picks up his commitment to popular pedagogy—the impulse to accessibility that led Lorenz, Tinbergen, and their colleague Karl von Frisch to cultivate an eager reading public and capture the Nobel Prize that eluded their predecessor.

It is a line of flight. The wasps fly straight through here, veering off in unanticipated directions, touching down at decisive moments. They flee science to foment Fabrean wonder among the modern creationists, for example, and sometimes they appear in more intriguing places, as in the imagination of the influential philosopher Henri Bergson, a great admirer of Fabre’s (he attended the celebration at l’Harmas organized by Legros in 1910 that heralded the Provençal hermit’s belated journey to the limelight). Bergson listens to the description of the nine-times-stabbing

Ammophila

surgeon and develops his own idiosyncratic

metaphysics of evolution, which draws on Georges Cuvier’s early-nineteenth-century notion that animals, like sleepwalkers, are equipped with a “somnambulist” consciousness (“a kind of consciousness which is intellectually unaware of its purpose”).

38

Bergson offers an intuitional view of instinct as a “divinatory sympathy” and, like Fabre, opposes instinct to intelligence. But the opposition has a different basis. Where Fabre sees intelligence as the mark of human superiority, to Bergson it is a limited form of understanding, cold and external. Where Fabre sees instinct as mechanical and shallowly automatic, to Bergson it is a profound understanding, a kind of knowledge that takes us to “the very inwardness of life,” reaching back through the common evolutionary history of wasp and caterpillar, back before they diverged on the tree of life, back to a deep intuition of each other, so that the

Ammophila

simply knows how to paralyze the caterpillar without ever having learned and so that their dramas “might owe nothing to outward perception, but result from the mere presence together of the Ammophila and the caterpillar, considered no longer as two organisms, but as two activities.”

39

Still, as Bertrand Russell noted as early as 1921, “love of the marvellous may mislead even so careful an observer as Fabre and so eminent a philosopher as Bergson.”

40

Fabre got a lot wrong about the hairy

Ammophila

, and it is on plain empirics that his critique of natural selection has been most effectively dismissed. This is not, it seems, a zero-sum game after all. It is true that, in general, the wasp paralyzes its Lepidoptera larvae with multiple stings, one to each segment. But the operation is not so miraculously accurate, nor so consistent, nor does it always follow the same order. Nor does the caterpillar even survive every time. Sometimes the larvae feed off its putrefying body. Sometimes they are killed by its thrashing torso. Moreover, as both reflexive and hormic theorists suggested, the wasp adjusts its behavior in response to changing external stimuli, such as climate, the availability of food, and the condition and behavior of its prey. And it readily alters the sequence and (what, for want of a better term, we might call) the logic of its actions for reasons that may be self-evidently necessary or, on other occasions, quite opaque. Wasps have been observed stinging forty separate larvae and then choosing to drag the forty-first, unparalyzed, to their nest. They

have been recorded paralyzing their prey but not following this action with any kind of nest building. They have been seen stinging at random, opportunistically, apparently just trying to get a good shot in. And it has been discovered that their sting is an injection as well as a stab and that it contains poison that produces instant paralysis and the longer-term effect of inhibiting metamorphosis and maintaining the larval body in a supple state, the effect on the victim less percussive than chemical.

41

There’s something uncanny here. And it’s not only the wasp. Herrnstein was right to point to the mysticism at the heart of Fabre’s account. He understood that the “vague wonder” that readers take from Fabre is the most potent legacy of the intuitional position. Yet it has its paradoxes too. Fabre pleads with us to understand that these animals are acting blindly, automatically, without will or intention. And to get there, he revels in the animals’ behavior, believing that the more complex it is and the more rational it appears, the more devastating his unmasking of it as no more than blind instinct, the more crushing his denunciation of the transformists that follows. These wasps are “surgeons” who “calculate” and “ascertain.” Their victims “resist.” But the effect is unforeseen. Fabre is enthralled. And the wasps claim the stage. He is their host. They speak through him, live through him. His prose leaves us not with a sense of the insects’ insufficiencies but with a profound impression of their capacities. A profound impression of the wasps’ capacities, that is, and of Fabre’s too. Despite his insistence, it is not instinct that is miraculous but the animals themselves.

The celebrity Fabre enjoyed in his final years did not long survive his death. Though there was little possibility of his embrace by the scientific community, literary fashion ensured that his stature as a nature writer would also rapidly fall. Nowadays, he is largely forgotten both in France and in the English-speaking world. Not even the creationists claim him.

Only in Japan is Fabre now a household name. There, he is a stalwart of the elementary school curriculum and is often a child’s first introduction to a natural world that soon comes alive in summer insect-collecting

assignments. He frequently returns in later life too, as parents introduce their children to the pleasures of natural history and recall the carefree days of their own youthful insect love. (“I write above all things for the young,” Fabre, a schoolteacher for a full twenty-six years, once told his critics in the scientific establishment; “I want to make them love the natural history which you make them hate.”)

42

As we might expect, he is a fixture of Japan’s numerous insectaria. But he also pops up in less likely places: incarnated in the resourceful boy hero of a current manga (

Insectival Crime Investigator Fabre

) in the top-selling biweekly omnibus

Superior;

as an anime character (in the series

Read or Die

, he is cloned as an evil genius with the power to turn insects loose against civilization); as a free promotional plastic figurine (a

souvenir entomologique

)—along with models of the cicada, the scarab beetle, the hairy

Ammophila

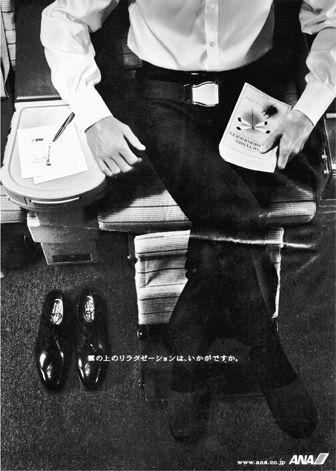

, and other favorites—in any of the thousands of 7-Eleven convenience stores throughout the country; and in luxury advertising, as a marker of male cosmopolitanism, intellectual curiosity, and a certain spiritual yearning.

43

But it is not just in schools, nature centers, and Japan’s vibrantly commodified popular culture that Fabre’s presence is felt. While his writings are available in English only in haphazard and elderly translation, a recent tally calculated that Japanese scholars produced forty-seven complete or partial editions of the

Souvenirs

alone between 1923 and 1994.

44

Okumoto Daizaburo, literature professor, insect collector, and founder-director of Tokyo’s new Fabre Museum, points out that the early history of these translations is especially interesting.

45

It was, after all, Osugi Sakae, the famous anarchist and author of the memorably subversive aphorism “Beauty is to be found in disarray,” who completed the first systematic translation of Fabre into Japanese and whose plan—cut short by his brutal murder in the police repression that followed the great Kanto earthquake of 1923—was to translate the entire

Souvenirs.

In 1918, around the time he first read Fabre, Osugi wrote: “I like a spirit. But I feel a repugnance when it is theorized. Under process of theorizing, it is often transformed into a harmony with social reality, a slavish compromise, and a falsehood.”

46

Though a committed Darwinian (he had already translated the

Origin of Species

), Osugi felt he had found a kindred spirit in Fabre. Captivated by

the energy of Fabre’s prose and by the pedagogical possibilities of popular science, Osugi was also drawn strongly to Fabre’s hostility to theorizing. The problem of theory, the charismatic writer-activist believed, lay less in its ability to explain than in its desire to order, less in its ambition to make sense of the world than in its appeal to the analytic over the experiential. The ordering impulse was a constraining impulse, one driven by the desire to dominate, to master, both intellectually and practically. The elevation of the rational, he asserted, impoverished the possibilities of apprehension. “To desire collapsing the universe into a single algorithm and to master all of reality with the precepts of reason” was, Fabre had written, a “grandiose enterprise,” not a grand one.

47

It didn’t seem to

matter to Osugi that this suspicion of global explanation arose from Fabre’s constant rediscovery of God’s hand in nature, a very different basis for wariness than his own.

48

I don’t know whether Okumoto is correct in his argument that Fabre’s appeal for Osugi lay in their shared nonconformity, but I like where it leads us. As Okumoto tells it, the revolutionary labor leader took inspiration from the schoolteacher-naturalist’s rejection of authoritarian pedagogy, his insistence on teaching girls as well as boys, and above all, his attitude toward categorization. (“A fig for systems!” Fabre exclaims in the

Souvenirs

when discussing taxonomists’ refusal to classify spiders as insects.)

49

Fabre’s celebration of the sensuality of inquiry, his rejection of authority, and his democratic accessibility fascinated Osugi—as it does Okumoto, who places Fabre alongside the celebrated naturalist and folklorist Kumagusu Minakata (1867–1941), another household name in today’s Japan and another figure honored for his nonconformity and independence: “These two idiosyncratic autodidacts never simplified their own thoughts into laws and formulas. Some people criticized their lack of strong, consistent theories, but they kept searching for the diversity of the world and kept seeing everything with a fresh eye. They are, indeed, what Rimbaud calls ‘

voyants.

’”

50

“Insect lovers are anarchists,” writes Okumoto elsewhere; “they hate following other people’s orders and try to create something like ‘order’ by themselves—or else they don’t care about such a thing at all!”

51

Insect lovers, he says, see the world from the place of the insect, from inside the life of the animal, from within its micro world. They pry into life, not death.

There’s another insect lover who might help here. Imanishi Kinji, ecologist, mountaineer, anthropologist, founder of Japanese primatology, and best-selling theorist of nature study (

shizengaku

), began his career in the 1930s studying mayfly larvae in the Kamo River, in Kyoto. A theorist of evolution, Imanishi was no theoretical Fabrean. But he was no Darwinian either. Like Osugi’s hero, the great anarchist Peter Kropotkin, Imanishi saw cooperation as the motor of evolution, rejecting both inter- and intraspecific competition as the basis of natural

selection. Imanishi stressed the connection and harmonious interaction among living things but insisted that the meaningful ecological units are societies, outside of which an individual cannot survive. Individuals come together not for reproduction but because they have needs in common, which they meet through collaboration. With its interest in cooperating groups rather than competing monads, his

shizengaku

is, he maintained, a Japanese view of evolution, distinct from a Darwinian system ideologically rooted in Western individualism.

52

Like Fabre, Imanishi attracted considerable condescension from professional biologists in Europe and North America, who scented an anti-scientific anti-Darwinism at work. But Imanishi’s ideas have widespread popularity in Japan.

53

Even though there is little overlap between the architecture of Imanishi’s thought and Fabre’s natural historical theology, there is an unambiguous affinity. “There are people in the world,” Imanishi wrote in 1941,