Insectopedia (12 page)

As everyone knows, the speed of urban growth and transformation in Shanghai is stunning. In less than one generation, the fields that gave the crickets a home have all but gone. Now, dense ranks of giant apartment buildings, elongated boxes with baroque and neoclassical flourishes, stretch pink and gray in every direction, past the ends of the newly built metro lines, past even the ends of the suburban bus routes. The spectacular neon waterfront of Pudong, the symbol of Shanghai’s drive to seize the future, is barely twenty years old but already under revision. I marvel at the brash bravery of the Pearl Oriental Tower, the kinetic multicolored

rocket ship that dominates the dazzling skyline, and think how impossible it would be to build something so bold yet so whimsical in New York. Michael and his college-age friends laugh. “We’re a bit tired of it, actually,” Michael says.

But they also know nostalgia. Only a few years ago, in what seems like another world, they helped fathers and uncles collect and raise crickets in their neighborhoods, among close circles of friends, in and out of one another’s homes and alleyways, sharing a daily life that the high-rise apartments have already mostly banished. Downtown, remnants of that life are visible in pockets not yet rebuilt or thematized. Sometimes, though, residents are merely waiting, surrounded by their neighbors’ rubble, holding out against forced relocation to distant suburbs as the government clears more housing, now for the spectacle of Expo 2010.

Eleven miles from the city center and a crowded fifteen-minute bus ride from the huge metro terminus at Xinzhuang, the township of Qibao is a different kind of neighborhood. An official heritage attraction, a stroll through a past disavowed for its feudalism during the Cultural Revolution but now embraced for its folkloric national culture, Qibao is newly elegant, with canals and bridges, narrow pedestrianized streets lined with reconstructed Ming- and Qing-dynasty buildings, storefronts selling all kinds of snack foods, teas, and craft goods to Shanghainese and other visitors, and a set of specimen buildings skillfully renovated as sites of living culture: a temple with Han-, Tang-, and Ming-dynasty architectural features, a weaving workshop, an ancient teahouse, a famous wine distillery, and—in a house built specifically for the sport by the great Qing emperor Qianlong—Shanghai’s only museum dedicated to fighting crickets.

All these crickets were collected here in Qibao, says Master Fang, the museum’s director, standing behind a table laden with hundreds of gray clay pots, each containing one fighting male and, in some cases, its female sex partner. Qibao’s crickets were famous throughout East Asia, he tells us, a product of the township’s rich soil. But since the fields here were built on in 2000, crickets have been harder to find. Master Fang’s two white-uniformed assistants fill the insects’ miniature water bowls with pipettes, and we humans all drink pleasantly astringent tea made from his recipe of seven medicinal herbs.

Master Fang has considerable presence, the brim of his white canvas hat rakishly angled, his jade pendant and rings, his intense gaze, his animated storytelling, his throaty laugh. Michael and I are drawn to him immediately and hang on his words. “Master Fang is a cricket

master

,” confides his assistant Ms. Zhao. “He has forty years’ experience. There is no one more able to instruct you about crickets.”

Everyone at the museum is caught up in preparations for the Qibao Golden Autumn Cricket Festival. The three-week event includes a series of exhibition matches and a championship, with all fights broadcast on closed-circuit TV. The goal is to promote cricket fighting as a popular activity distinct from the gambling with which it is now so firmly associated, to remind people of its deep historical and cultural presence, and to extend its appeal beyond the demographic in which it now seems caught: men in their forties and above.

Twenty years ago, everyone tells me, before the construction of the new Shanghai gobbled up the landscape, in a time when city neighborhoods were patchworks of fields and houses, people lived more intimately with animal life. Many found companionship in cicadas—“singing brothers”—or other

musical insects that they kept in bamboo cages and slim pocket boxes, and young people, not just the middle-aged, played crickets, learning how to recognize the Three Races and Seventy-Two Personalities, how to judge a likely champion, how to train the fighters to their fullest potential, how to use the pencil-thin brushes made of yard grass or mouse whisker to stimulate the insects’ jaws and provoke them to combat. They learned the rudiments of the Three Rudiments, around which every cricket manual is structured: judging, training, and fighting.

The irony is that despite the erosion of the popular base needed to guarantee its persistence, cricket fighting is experiencing a revival in China. Even as it loses out to computer games and Japanese manga with the young, it is thriving among older generations. Yet it’s an insecure return that few aficionados are celebrating. For even as the cricket markets flourish, the cultural events blossom, and the gambling houses proliferate, much of the talk is marked by the same anticipatory nostalgia, a sense that this, too, along with so much else about daily life that only a few years ago was taken for granted, is already as good as gone, swept away—not for the first time in recent memory—into the dustbin of history.

Master Fang pulls an unusual cricket pot from the shelf behind him and runs his finger over the text etched on its surface. In a strong voice, he begins to recite, drawing out the tones in the dramatic cadences of classical oratory. These are the Five Virtues, he announces, five human qualities found in the best fighting crickets, five virtues that crickets and humans share:

The First Virtue:

When it is time to sing, he will sing. This is trustworthiness [

xin

].

The Second Virtue:

On meeting an enemy, he will not hesitate to fight. This is courage [

yong

].

The Third Virtue:

Even seriously wounded, he will not surrender. This is loyalty [

zhong

].

The Fourth Virtue:

When defeated, he will not sing. He knows shame.

The Fifth Virtue:

When he becomes cold, he will return to his home. He is wise and recognizes the facts of the situation.

On their tiny backs, crickets carry the weight of the past.

Zhong

is not ordinary loyalty; it is the loyalty one feels for the emperor, the willingness

to lay down one’s life, to not shirk one’s ultimate duty.

Yong

is not ordinary courage; it is, once again, the readiness to sacrifice one’s life and to do so eagerly. These are not simply ancient virtues; they are points on a moral compass, codes of honor. As anyone will tell you, these crickets are warriors; the champions among them are generals.

The passage on Master Fang’s pot is from the unquestioned urtext of the cricket community, the thirteenth-century

Book of Crickets

by Jia Sidao.

1

No mere cricket lover, Jia is remembered still as imperial China’s cricket minister, the sensual chief minister in the dying days of the Southern Song dynasty, so absorbed in the pleasures of his crickets that he allowed his neglected state to tumble into rack, ruin, and domination by the invading Mongols. The story is told by his official biographer:

When the siege of the city of Xiangyang was imminent, Jia Sidao sat on the hill of Ko as usual, busying himself with the construction of houses and pagodas. And, as usual, he continued to welcome the most beautiful courtesans, streetwalkers, and Buddhist nuns as his prostitutes and to indulge in his routine merry-making.… Only the old gambling gangsters, looking for play, approached him; no one else dared peek into his residence.… He was squatting on the ground with his entourage of concubines engaged in a cricket fight.

2

The historian Hsiung Ping-chen points out that whatever this incident might say about Jia’s sense of responsibility and his personal rectitude, it also casts him as a man whose failings were at least irredeemably human and whose passion for crickets had a democratic stubbornness. From this point on, Jia “was enthroned as the deity in China’s game world,” she writes. “For centuries, his name liberally adorned all covers of books on crickets, call them collections, histories, dictionaries, encyclopedias or whichever title you wish, concerning catching, keeping, breeding, fighting, and, of course, gambling.”

3

There is much ambivalence surrounding these crickets, even in this one story. It’s so many things: a sorry tale in which crickets are just another expression of feudal decadence—the counterpoint to socialist modernity and the ready analog for contemporary injustices; a cautionary tale in which the moral effects of compulsive cricket fighting on individual and society are only too plain; a seductive tale in which the problem of desire—with its ever-present threat of addiction or other

disorder—is part of the crickets’ magic, in the spell they cast over the most important man in the empire, a spell at once enthralling and enslaving. And more prosaically, it’s a cultural tale in the blandest sense, extending through the centuries, demonstrating the historical reach of crickets as socially important beings, as historical agents of the first degree.

As if all that weren’t enough for one figure (who, of course, had another public career as a politician of considerable importance), there is the

Book of Crickets

, the very foundation of cricket knowledge, the mostly unnamed source to which everyone—Master Fang, Mr. Wu, Boss Xu—is referring when he tells me that this cricket culture is very deep knowledge, that it comes to us directly from the ancient books. And we can put this in another language to say simply that Jia Sidao’s

Book of Crickets

is not only the earliest extant manual for cricket lovers, it is also perhaps the world’s first book of entomology.

4

There are written records of people fighting crickets in China as early as the Tang dynasty (618–907). But it’s only with Jia’s

Book of Crickets

, with its detailing of intimate insect knowledge, that we can be sure that cricket raising and fighting had become a widespread and elaborate pastime. In fact, it was in the 300 or so years between Jia’s Southern Song dynasty and the mid-Ming dynasty that an organized market developed around these animals.

5

This market reached its height during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), linking town and country in commerce and culture and stimulating an extraordinarily beautiful material culture of implements and containers.

6

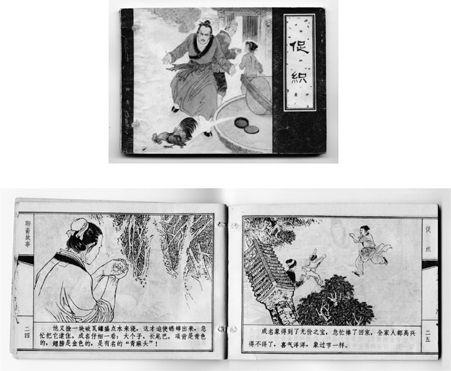

It eclipsed the crickets’ older role as singing companions, producing an extensive network of gambling houses with specialized workers and complex rules, an equally energetic but largely ineffectual series of state attempts at prohibition, and—as if it were the expression of Jia’s extravagant desire—sweeping up people of all ages in an activity that was accessible to all social groups and for several centuries was truly popular, as can be seen quite clearly in paintings and poetry and in classic stories like Pu Songling’s “The Cricket,” a tale of bureaucratic oppression and mysterious transformations, a tale of depth, subtlety, and social criticism familiar to everyone I met in Shanghai, a tale that I was able to find in a used-book stall as a finely drawn comic from the early 1980s, a storytelling form once as popular in China as it still is in Japan and Mexico.

7