Insectopedia (14 page)

It is now that the happy times officially begin. I haven’t seen it myself, but it’s easy to visualize from the stories: whole villages out in the moonlit fields; young, old, men, women, flashlight bound to the head, listening for the crickets’ song, searching around tombstones, poking the earth and brickwork with sticks, throwing water, pinning the insects like startled rabbits in the beams of light, gathering them in small nets, trapping them in sections of bamboo, taking care not to damage their antennae, carrying them home, ordering them by their diagnostic qualities. In a few days of night- or daytime collecting, a family can amass thousands of crickets, ready to be sold directly to visiting buyers or to be carried to local or regional markets.

Li qiu

rings alarm bells throughout China’s eastern cities. In Shanghai, as well as in Hangzhou, Nanjing, Tianjin, and Beijing, it is the signal for tens of thousands of cricket lovers to head for the railway stations. They pack the trains to Shandong Province, which, during the twenty years in which crickets have become scarce in Shanghai, has established itself as the regional collecting center, the source of the finest warriors, known for their aggression, resilience, and intelligence.

Who knows how many answer the crickets’ call and make the ten-hour journey from Shanghai to Shandong? Mr. Huang, feathering a client’s hair in his storefront salon, tells us it can be near impossible to

find a rail ticket during this period. Xiao Fu, seated in the doorway of his antiques stall, showing us his collection of rare cricket pots—presenting me with a pair from Tianjin (thick walled and pocket-size to warm the cricket close to your body)—estimates that he is 1 of up to 100,000 Shanghainese who go. Others reckon that 500,000 people arrive from eastern China during this four-week period and that upward of 300 million yuan flows into the local economy from the Shanghainese alone.

11

Who travels to Shandong? Always the same answer: if, like Mr. Huang and Xiao Fu, you habitually bet more than 100 yuan on a fight, you make the journey; if, like Mr. Wu, you bet less, you wait for the cricket markets in Shanghai to fill with insects from the provinces and make your selections there. Xiao Fu tells us that he is like most cricket lovers, just a small-to-middling gambler. But the 3,000 to 5,000 yuan he spends each year in Shandong seems sizable next to the 12,000 yuan he brings in from antiques. Still, there are millionaire cricket lovers taking the train these days who are willing to slap down 10,000 yuan to scoop up a single general. So this year Xiao Fu did what more and more visitors do: he rented a car with his friends and toured the villages dotted throughout the countryside on the roads of Ninyang County, and he avoided the crowds in the main market at Sidian.

Often, I’m told, when buyers like Xiao Fu arrive in outlying villages, the first thing they do is pay five yuan for a table, a stool, some tea leaves, a thermos, and a cup. Then, within moments of settling down, they are besieged by villagers pushing cricket pots under their noses, crying, “Look at mine! Look at mine!” Some of the sellers have pricey, good-looking crickets, but others are children and elderly people with only the cheapest insects to sell.

12

The more successful sellers establish and maintain connections to buyers, perhaps have them come to the village to trade with them, perhaps even have them lodge in their home. The visitors might be gamblers like Xiao Fu, or they may be Shanghainese traders looking to purchase in bulk. Or they might be wealthier farmers or small businesspeople from local towns and villages who have found ways to cross the far-higher entry barriers to sell on the markets in Sidian or Shanghai or both. Or perhaps they are Shandongnese who do business by selling insects to others—Shanghainese or Shandongnese—who sell them on the urban markets. While it’s clear that for the village collectors who every year turn to crickets for direly needed cash income,

this is a moment of real, though perhaps desperate, opportunity, it’s also clear that those who prosper the most in this economy are those who have the most to begin with and that the cricket trade, a vital supplement to the rural economy in Shandong, as well as in Anhui, Hebei, Zhejiang, and other eastern provinces, is also an engine of social differentiation serving to deepen what are already widening chasms of inequality.

Yet it’s an insecure and destructive engine. Through the 1980s and ’90s, as the cricket markets in Shandong took off, the county of Ninjing was the most popular destination for buyers. But after more than a decade of intensive collecting, the quality of the crickets began to decline noticeably, and Ninjing’s preeminence was usurped by its neighbor Ninyang, which now markets itself as “China’s Sacred Fighting-Cricket Location.” In recent years, however, the overexploitation of crickets in Ninyang has forced local collectors (as well as visitors like Xiao Fu) to expand their range, so that they now comb the countryside and villages within a radius of more than sixty miles from their temporary bases. The pressure of unregulated collecting on the crickets is “like a massacre,” writes one contemporary commentator.

13

Night hunting, which used to occupy villagers from nine in the evening until four in the morning, now takes them away from their homes until noon.

Just one month after

li qiu

, as warm August nights ease into cold September mornings and white dew appears on country fields,

bai lu

marks the end of the collecting season. Sensing the chill in the air, the crickets call a halt, heading back into the soil, digging down with their powerful jaws, weakening their most precious fighting asset, and ruining their value as commodities. Carefully packing up their haul, the last Shanghainese retrace their journey home, though this time they share the trains with Shandongnese traders off to stake their claim in the city’s cricket markets.

At Wanshang, the largest flower, bird, beast, and insect market in Shanghai, these traders, mostly women, sit in rows in the center of the main hall with their crickets laid out neatly before them in small pots with lids cut from tin cans. Around the market’s edges, permanent stalls are occupied by Shanghainese dealers, also newly returned, their clay pots arrayed on tables, the insects’ origin chalked up on a blackboard behind them.

The same pattern is repeated at cricket markets throughout the city. At Anguo Road, in the grim shadow of Ti Lan Qiao, Shanghai’s largest jail, and again in what Michael called new Anguo Road—rapidly opened in a disused lot following a police raid—Shanghainese sellers sit at tables while traders from the provinces, squatting on stools, lay out their pots on the ground in their own distinct areas. This visible geography mirrors pervasive tensions in Shanghai and throughout contemporary China between urban residents and what is officially known as the “floating population,” a vast number of people to whom the government denies urban residency status (with its associated permit and social benefits) but who anyway fill the lowest-paying and most dangerous jobs in the construction, service, and sweatshop sectors.

14

Even though the provincial traders at these markets don’t plan to stay in Shanghai and even though they are likely to be relatively prosperous in rural terms (some are farmers; some are year-round traders of various products; one man I talked to dealt in cell phones), once in the city they are simply migrants, subject to harassment, discrimination, and expulsion. Nonetheless, for those who’ve made it here, these are potentially

happy times too. No matter that unemployment is up, gambling is down (after a series of police crackdowns), and business accordingly slowed, most expect to do well. By minimizing their expenditures—traveling with relatives, going home infrequently, carrying as much stock as possible when they return, and sleeping in cheap “basement hotels” close to the market—provincial traders can make considerably more in these three months than they will in the entire rest of the year. At least that’s what traders—including an impressively organized woman from Anhui who said that last year she took home a full 40,000 yuan—told me again and again.

Shanghainese traders don’t sell female crickets. Females don’t fight or sing and are valued only for the sexual services they provide to males. It’s the provincial traders who deal in these, selling them in bulk, stuffed into bamboo sections in lots of three or ten, depending on their size (bigger is better) and coloring (a white abdomen is best). Females are cheap, and at a first glance that takes in these traders’ apparently subordinate situation in the market, it seems they sell only cheap animals, female and male.

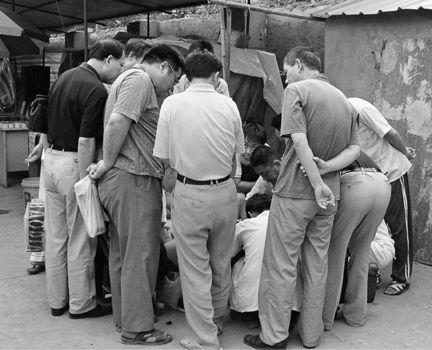

The signs in front of the Shandongnese traders say ten yuan for each male, sometimes two for fifteen. The buyers file past their pots, browsing the rows with an air of detachment, occasionally lifting the lids to peer inside, taking the grass brush, stimulating the insect’s jaws, perhaps shining a flashlight to gauge the color and translucence of its body, trying to judge not only its physical qualities but also that less tangible and even more critical fighting spirit. Despite their studied indifference, they’re often drawn in, quickly finding themselves bargaining for an insect priced anywhere between 30 and—if the buyer is a genuine big boss—as much as 2,000 yuan. Only children, novices like me, the elderly, the truly petty gamblers who play crickets for fun, and bargain hunters who believe their eye is sharper than the seller’s will buy the cheap crickets, it seems.

But how do you judge an insect’s fighting spirit without seeing it fight? Groups of men crowd around the Shanghainese stalls. Michael and I aren’t tall or short enough to see between shoulders or legs. Eventually, someone moves aside to share the view: two crickets locking jaws inside their tabletop arena. The stallholders tend to the animals like trainers at a real fight. But they’re seated in chairs, pots piled around

them, and as the match progresses, they deliver relentless patter, inciting interest like auctioneers, talking up the winner and attempting to raise its price.

This is a risky sales strategy. No one buys a loser, so the defeated are quickly tossed into a plastic bucket. And if, as often happens, the winner isn’t sold either, he has to fight again and may be beaten or injured. The seller relies on his ability to inflate the winner’s price enough to compensate for the collateral losses. But the woman from Shanghai who eagerly waves us over as she spoons tiny portions of rice into dollhouse-size trays, tells us that the Shanghainese insist on watching the crickets fight before they put their money down, that they like to shift the risk to the seller. It is starting to look as if the divisions between metropolitan and provincial are expressed not only in the spatial arrangements (which make the market look like an allegorical tableau of society at large) but also in the distinctive selling practices of the different groups, so that buyers stroll in and out of two distinct worlds as they browse, two worlds with explicit boundaries marked by distinct codes, aesthetics, and experiences, two racialized worlds perhaps.

“Shandongnese don’t dare fight their crickets,” the woman continues in a tone that seems congruent with the discriminations that surround us. She is lively and straightforward, generous too, inviting us to share her lunch and giving me a souvenir cricket pot, disappointed that I won’t take the insect as well, enjoying initiating us and not about to be silenced by her irascible husband no matter how many times he looks up from his warriors to sound off in our direction. She’s expounding on her neighbors, the Shandongnese traders. “They sell their crickets as brand-new to fighting,” she says, and then—so casually it almost slips past, and it is only thanks to Michael’s quickness and to the violence of her husband’s reaction that I realize it—she is telling us that crickets circulate throughout the market, unconstrained by social and political division. She explains that they pass not only from trader to buyer but also, without prejudice, from trader to trader, from Shanghainese to Shandongnese and from Shandongnese to Shanghainese. And as they travel through these crowded spaces, they gain and even recover value; they’re born again: losers become ingenues, cheap crickets become contenders; they change their character, their history, and their identity. Caveat emptor.

But how fascinating and even inspiring that the politics of racial difference diagrammed so concretely in this highly spatialized marketplace and conforming so fully (too fully, in a game of double bluff, it turns out) to social expectation is not only an expression of a dismal social logic but also a technology of commerce that creates lively crosscutting dependencies and solidarities. And this thought led me again to the animals who make all this possible, confined to their pots, traveling like slaves really, like chattels, making their way between stalls and pitches, completing circuits, breaching boundaries, and forging new connections, gathering new histories and new lives, unable to prevent themselves from minimizing their captors’ exposure to loss, unable to avoid collaborating in their own demise.