Insectopedia (5 page)

These watercolors are realistic but not naturalistic. With rare exceptions, her animals lack all animation. Their physicality foregrounded, they have the aura of specimens. Each painting is a portrait, and each insect is a subject, a specific individual. She tells me, “I like that the insect can be itself. That’s why I choose to paint the individual as it is. I could, for instance, paint one that has five different defects that I find in an area. I don’t do this. I want to show the individual.” On display, the insect hangs, massive, stunning in its detail, supplemented by a label that identifies the date and site of its collection, as well as its irregularities, and that grounds the atemporal image in time, place, and politics. Sharing much of the visual grammar of the biological sciences, the paintings seem mutely dispassionate, resolutely documentary. But so thoroughly in the world, they shimmer with emotion.

Cornelia once told me that the first time she saw a deformed leaf bug, so tiny, so damaged, so irrelevant, she lost her mental balance, her perspective, her sense of scale and proportion. For a moment, she was unsure if she was looking at herself or the animal. She paused in her narrative. “Who cares about leaf bugs?” she said. “They’re just nothing.” She was recalling her earlier life, as the teenage daughter of famous artists, describing how she hung back in the shadows, unobserved, as her parents entertained Mark Rothko, Sam Francis, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and other luminaries in New York, Paris, and Zürich (“No one would even see me or recognize me…. I would never interfere”). And she was recalling how in twenty years her husband never visited her studio, and how, when her son was born, the doctor came into her room and made a drawing for her to break the news that her child had a club foot, and how, when she saw that first deformed leaf bug in Sweden, it had a crippled foot too. And she was telling me how, when she saw that

first crippled insect, in the shock of all those experiences colliding so suddenly with such unanticipated force, she had to fight physically to stop herself from throwing up.

And just a few moments later, in the failing afternoon sunlight in her Zürich apartment, she said, “In the end, the picture is everything. Nobody sees the insect itself.” And it was my turn to pause, because I didn’t quite know what she meant. It sounded like a lament, a disappointment that her images are too instantly domesticated, reduced to the iconic, that they too easily make the leap from invisibility to enormity, too effectively stand in for human fears, too readily bring self-concern to the fore, so that the individual insect—the one she found (“It’s heaven on earth!”), captured (“They can move very quickly”), killed with chloroform (“I always tell myself this is the last summer”), pinned, labeled, added to the thousands already in her collection, and finally came to know so intimately through microscope and brushes—seems again and again to be overlooked, to become lost.

But then I remembered Cornelia saying that if she were freed of the compulsion to paint deformities, if she were free to paint whatever she chose, her work would follow the path laid out in the painting of the mutant eyes she completed before her life was interrupted by the journey to Österfärnebo. And I realized that her lament was not only for the loss of the individual insect. In that painting, she offers the insect not as being or subject but as its antithesis: the insect as aesthetic logic, as coalescence of form, color, and angle. This is work that draws explicitly on her history in concrete art, an international movement centered in postwar Zürich, in which—because of the prominence in the group of her father, Gottfried Honegger—she received her initial aesthetic training. (Cornelia’s mother, Warja Lavater, was widely known as an innovative graphic artist and maker of artists’ books.)

Concrete paintings tend toward geometric patterns, high-contrast color blocks, glassy planes, and the refusal of figurative or even metaphorical reference. Kazimir Malevich’s programmatic

White on White

(1918), a white square painted on a white ground, is perhaps the movement’s founding document. Casting themselves as aesthetic radicals breaking with the conservatism of representational art, Max Bill, Richard Paul Lohse, and the other founders of concrete art looked to Soviet constructivism, to the geometry of Mondrian and De Stijl, and to the formalism

of Bauhaus. In his 1936 manifesto,

Konkrete Gestaltung

(

Concrete Formation

), Bill wrote, “We call those works of art concrete that came into being on the basis of their own innate means and laws—without borrowing from natural phenomena, without transforming those phenomena, in other words: not by abstraction.”

18

Abstract art, searching for a visual language based in symbols and metaphor, is still “object painting,” is still tied to the object it mimics, is still asking what that thing is, how it can be made sense of, how it can be communicated. For concrete artists, the work should speak of nothing but itself. It should reference nothing outside itself. It should leave the viewer complete interpretive freedom. Its signs and its referents should be one and the same: form, color, quantity, plane, angle, line, texture.

From the 1940s, the group was centered in Zürich, a wartime refuge for critical intellectuals. Its influence, though, was felt throughout Europe (notably in the op art of Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely), in the United States (in color-field painting and minimalism), and in Latin America (especially among Brazilian concrete and neoconcrete artists, such as Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Cildo Meireles). The movement was varied, but it found an early unity in the search for an art that would be the visual and tactile expression of pure logic (“the mathematical way of thinking in the art of our times,” as Bill put it).

19

As the concretization of the intellect and the removal of interpretation, it was a direct riposte to Surrealism’s appeal to the unconscious. Yet subjectivity proved to be a stubborn presence. Concrete paintings and sculptures were also the product of the artists’ arbitrary choices. Probability, chance, and randomness promised a solution, and the search for effective ways to integrate them into the artistic process became an important preoccupation.

It took me a long time to understand the importance of these aesthetics for Cornelia. On the one hand, it seemed clear that her sensuous attention to the insect contravened their most basic premise: the adherence to Malevich’s “nonobjectivist” determination to shatter the connection between art and material objects. Yet I knew from our conversations that in the moment of painting, Cornelia sees form and color, not the independent object. Nor is there anything accidental in the formality of her portraits or the repetition of the poses. All is geometric, the insects located on a grid that she systematically completes. Her method is both highly precise and, in the sense that the outcome is contingent on what

is present under the microscope, substantially random. It is not unusual that after finishing a painting, she discovers that the insect is deformed in ways she hadn’t noticed before. Her painting practice, she insists, creates a rigorous break, removing her environmentalist politics and her sympathies for the animal from the image, so that the paintings themselves are freed of her presence. “My task,” she told me, echoing Max Bill, “is just to show [the insect] and to paint it, not to judge it.” Viewers, she says, must search for meaning in the picture unburdened by her message.

But, I wondered, with the strength of her commitment to anti-nuclear politics and to the insects themselves and with the descriptive labels accompanying the images and all the controversy that has surrounded her work, how could either she or the viewer avoid judgment? “I do think it’s possible,” she replied. “When I sit there and draw, I want nothing else than to be as precise as possible. It is not simply politics: I have a deep interest in structure in nature.” But what kind of non-object art can be based so strongly in objects? Can her pictures be both “deeply in the world,” as she puts it, and speak of nothing beyond themselves? Isn’t there a contradiction between these twin impulses of her painting: to recognize the individual insect and simultaneously to efface it into an aesthetic logic of form? Yes, she says without hesitation, her work is really neither concrete nor naturalistic. And according to many, it is also neither science nor art. Perhaps, she laughs, that’s why she so rarely manages to sell any of it!

Much later that evening, with both of us fading fast and our conversation faltering, she returns again to this question. We are talking about her involvement in campaigning, how an exhibition of her paintings organized by the World Wildlife Fund toured sites slated for nuclear-waste disposal, when she abruptly shifts the topic. “It’s the artistic question,” she says suddenly. “How to show structure … It’s a question of how can I show the structure of what I find.” It is not simply politics. But how to assert this when the politics overshadows everything and the painting is far more complex than it appears?

And then, in frustration and from more than a little exhaustion, her voice dropping to little more than a whisper: “Everything is always so focused on those watercolors …”

In the years since the

Tages-Anzeiger

articles, Cornelia has devoted herself to investigating the health of insects near nuclear power plants in Europe and North America. She has collected at Sellafield, in northwest England (the location of the 1957 Windscale disaster); around the Cap de la Hague reprocessing plant in Normandy; at Hanford, Washington (site of the plutonium factory for the Manhattan Project); on the perimeters of the Nevada Test Range; at Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania; in Aargau during every summer from 1993 to 1996 (the map below is based on data from 2,600 Aargau insects); and as an invited participant on a 1990

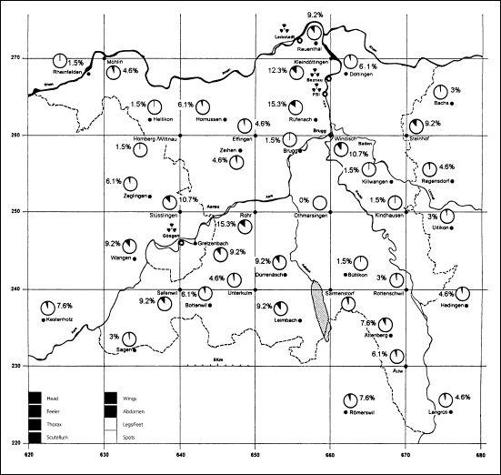

tour of the zone surrounding Chernobyl. She lectures, speaks at conferences, organizes exhibits of her paintings in collaboration with environmental groups, and is working on a large-scale project with the group Strom ohne Atom (Electricity without Nuclear Power) to document the distribution of eleven types of morphological deformities (missing and misshapen feeler segments, wings of different lengths, irregular chitin, misshapen scutella, deformed legs, and so on) among sets of fifty insects she is collecting at each of twenty-eight locations in Germany.

She has succeeded in forming some important relationships with scientists. At Cap de la Hague, for example, Jean-François Viel, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of Besançon who has identified a leukemia cluster among local residents, collaborated on the statistical analysis of her collection. But in general she is more cynical now about enlisting experts and instead responds to critics directly through her research design: her data collection is more systematic, her documentation more rigorous, and her paintings are no longer the rapid sketches of those first frenetic field trips. In interviews and publications, she has begun to explicitly address methodological questions, arguing that there can be no reference habitat on a planet thoroughly polluted by fallout from aboveground testing and emissions from nuclear power plants and being careful to point out that she is documenting induced deformities to somatic cells rather than heritable mutations. (“I cannot say they are mutations because I cannot prove it, and if I cannot prove it, I don’t think I can say it,” she tells me.) In this way, she emphasizes her own expertise, strengthening her intervention in those nonscientific arenas where her talents are valued, publicizing her findings through environmental organizations, mass media, and cultural institutions.

These tactics free Cornelia to act as an environmentalist, to participate in a world in which the politics of scientific proof are inverted by the precautionary principle, which asserts that a well-founded fear of potential danger is a sufficient basis on which to oppose the deployment of a policy, practice, or technology. They free her from the shadow of science, from having to assert herself against a set of methodological and analytic standards that are always impossible to achieve because they are always initially institutional—that is, recognized only among those with the requisite credentials (a doctorate, an affiliation, a professional network, a funding

history, a publishing record). The irony, of course, is that no one understands her scientific inadequacies better than Cornelia herself. And no one—as the tone of those early articles and her petitioning of professors showed—was more willing to accept the conventional subordinate role of the amateur as the handmaiden of the scientific expert. It strikes me that the relentlessness of her work has grown in direct proportion to her understanding of its importance. And that her understanding of her work’s importance has increased as it has become clear how isolated is her quest for recognition of the effects of low-level radiation on insects and plants. Where would she be now if she hadn’t faced such hostility and rejection? “It’s something I don’t understand,” she told me in Zürich, “because if I had only found one leaf bug with its face shifted that would be enough to ask what was going on.” And yet somehow, despite all this, there are signs of change. Perhaps the current interest in nuclear power as a “green” fuel has given new urgency to her message, perhaps it is the fruit of her relentlessness, but she has recently had an unexpected success, publishing a prominent (and beautifully illustrated) article—which, as we would expect, pulls no punches—in the specialist peer-reviewed journal

Chemistry and Biodiversity.