Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (69 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

Three months later, Stones manager Eric Easton attempted to change Sullivan’s mind. Requesting another booking, Easton wrote: “

I know that these men are controversial entertainers, but it would seem that they have established quite a following in America and indications are that their popularity will increase.” Ed wasn’t going to make Easton’s job easy. “

We were deluged with mail protesting the untidy appearance—clothes, and hair of your Rolling Stones,” he replied to Easton. “Before even discussing the possibility of a contract, I would like to learn from you, Eric, whether your young men have reformed in matter of dress and shampoo.” Whatever Easton said must have convinced Sullivan, and at any rate the potential Nielsen boost from the group made it tough for him to stand on principle. Several months later Ed introduced a Stones set that featured “The Last Time” and “Little Red Rooster.” Along with the Rolling Stones that season were the other leading troupes in the British Invasion, including The Animals performing “House of the Rising Sun,” the

clean-cut Dave Clark Five (who insisted on lip-synching, which Ed frowned on), singing “Anyway You Want It,” and Herman’s Hermits warbling “Mrs. Brown You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter.” Making her first of eleven appearances was Petula Clark, equipped with go-go boots, performing her number one hit “Downtown.” Motown was starting to take hold of the pop charts, and the Supremes—a Sullivan favorite—made their first of fifteen appearances. Before one of their sets, Ed introduced them with a windy laud, at the end of which he forgot their name, so he just bellowed,

“Here’s the girls!”

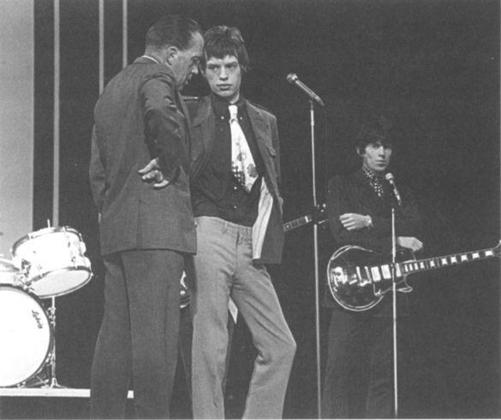

In rehearsal with Mick Jagger, September 1966. Sullivan tried to rein in the Stones on a number of occasions, with limited success. (CBS Photo Archive)

As prevalent as younger musicians were, they still shared the stage with Ed’s something-for-everyone mix. The same night Petula Clark sang “I Know a Place,” Alan King did a stand-up routine about how parents bother kids, the West Point Glee Club harmonized, and the Elwardos acrobats defied gravity. The Animals shared billing with Las Vegas crooner Wayne Newton; the Dave Clark Five shared billing with big band leader Cab Calloway. Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald performed a medley of Duke’s 1940s hits the same evening Ed introduced a clip from 1965’s The

Sound of Music

, after which Julie Andrews sang “My Favorite Things.” Football star Jim Brown chatted with Ed on a program in which a troupe of contortionists called the Morilodors, consisting of a man in a black mask with two female assistants, bent the human body into unlikely poses.

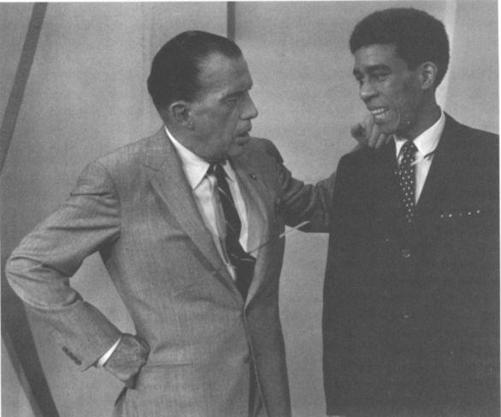

With Richard Pryor, in the mid 1960s. Sullivan fought CBS censors to allow the comic to perform material as he pleased. (CBS Photo Archive)

International dance stars Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn, of Britain’s Royal Ballet, performed an except from Tchaikovsky’s classic

Swan Lake

on the same show that juggler Ugo Garrido kept an odd assortment of objects in motion. Making his first of thirteen appearances was twenty-four-year-old comedian Richard Pryor, sharing the bill with the Three Stooges. Ed did a routine with the puppet Topo Gigio in which Topo was homesick and gets a call from his mama.

The eclectic mix was popular with the public, a fact that CBS sought to take advantage of. In 1964 the network asked Ed to expand

The Ed Sullivan Show

to ninety minutes. The program had long dominated its time slot; from the network’s perspective adding an extra thirty minutes was the easiest way to increase ratings. Ed agreed to the ninety-minute format, yet just a few weeks later, before actually adopting it, he demurred. The greater workload looked daunting, and worse, the longer format might not have been popular.

His change of heart did nothing to hamper negotiations for the new contract he signed that year. Ed decided he deserved a substantial raise and the network put up no argument. “

We will be presenting Ed every Sunday night just as long as he wants,” announced CBS-TV president James Aubrey after the signing. The showman’s paycheck jumped to $32,000 a week, with increases over the next seven years, scheduled to reach $47,000 a week by 1971. When reporters questioned him,

he revealed no contract details, noting only that CBS had been “

very, very generous.” (It might have punctured his image as Uncle Ed to admit he earned more every week than most families earned all year.) The show’s weekly production budget was pegged at $124,500; with graduated increases it was scheduled to reach $170,000 by 1971.

More important, the showman now owned

The Ed Sullivan Show

, previously owned by the network. Since the deal was retroactive, Sullivan Productions owned the copyright to all the shows back to 1948, and to all shows produced henceforth. Ed owned fifty-one percent of Sullivan Productions, with forty-nine percent held by Bob Precht and Betty Sullivan Precht. By most accounts it was Bob’s idea to take show ownership from the network. Ed’s son-in-law, who had been a novice assistant producer in the late 1950s, was now not just coproducer but also part owner of one of television’s highest rated programs.

In October, Ed booked one of his comic mainstays, Jackie Mason, in an evening that sparked a major conflict and generated a bevy of headlines. The young Borscht Belter benefited enormously from being a Sullivan favorite. Nothing had boosted his career more than his many

Ed Sullivan Show

appearances since Ed discovered him at the Copacabana in the early 1960s. Mason was part of a transitional school of comics who had taken a step past their 1950s forebears; he could poke fun at political figures yet offend no one, combining tried-and-true mother-in-law jokes with a lighthearted take on current events. His Sullivan impression made Ed laugh.

Mason remembered working with Ed as a process of negotiation. After the comic ran through his routine in Sunday’s dress rehearsal, Ed began editing. “

He was totally in charge of every move on the show, and he enjoyed running it,” Mason recalled. “But he was always generous to me because he seemed to like me a lot. Sometimes he tried to cut a minute, and I would say, ‘But that minute is the main transition to the next joke,’ and he would say, ‘Maybe you could make it half minute, because I really don’t have the time.’ ”

Back and forth they would go, with Sullivan attempting to shape his act at every turn. “So I would kibitz with him, to try to soften it, because he would seem very nervous about how it was going to work out.” Sullivan often acquiesced if Mason insisted. Over the course of his twenty Sullivan show appearances the comic saw Ed negotiate with many performers. “He treated different people differently in terms of how much he felt he needed them or how good he thought they were.” A comparative unknown might have no recourse in the face of Sullivan’s directives, but he usually treated the biggest stars with deference, Mason recalled.

Ed “was always an unpredictable commodity, because you couldn’t tell what mood he would be in, and who he would be attacking and who he would be settling for.… It was a sporadic, totally indefinable system,” the comic remembered. “He was insecure and uncertain about almost everything. He tried to be firm, but he wasn’t sure about how firm to be. He was very authoritative, but at the same time, he was malleable, because he wasn’t so sure of himself, so he would second-guess himself. To some people he came across as arrogant and obnoxious, but I don’t believe that. He was just somewhat insecure and he was trying to do the show as best he could. He was intensely preoccupied, but he wasn’t in any way arrogant.”

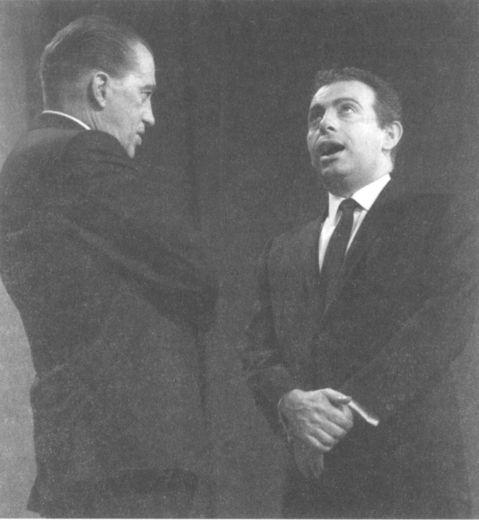

With Jackie Mason. Sullivan became enraged at Mason after a controversial appearance by the Borsht Belt comic. (CBS Photo Archive)

For Mason’s October 1964 appearance, with the presidential race between Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater nearing Election Day, the comic was told to drop his political material. As innocuous as it was, Sullivan felt it was too sensitive given the imminent election. That evening’s broadcast was partially preempted by President Johnson, who began an address to the nation at 8:30

P.M.

The show continued while the president spoke, resuming its broadcast around 8:52, with Mason in the middle of his routine. The preemption threw the schedule off-kilter, and Ed was anxious about running out of time. He began urgently gesturing to Mason to cut his act short, holding up two fingers for two minutes, then one finger as time elapsed. Mason’s jokes were met with silence as Ed’s frantic gesturing distracted the studio audience. Mason, afraid that home viewers would interpret the studio audience’s silence as a sign that he was bombing, began ad-libbing based on Ed’s hand gestures. “I thought I’d generate some laughs by making fun of him,” Mason said.

“What are you, showing me fingers? You got fingers for me, I’ve got fingers for you,” he said, as he comically mirrored Ed’s finger signs. The comedian’s gesticulations grew more exaggerated as the studio audience’s laughter fueled his improvising. “Who talks with fingers in the middle of a performance, you think they came here to watch your fingers?… If your fingers are such a hit, why do you need me, why don’t you come here and show your fingers?”

Mason concluded his act feeling like his performance was a hit, that he had rescued himself from a career disaster. But Ed felt differently. Visibly upset onscreen after Mason’s exit, he was livid after the program. As he saw it, the comic’s finger

improvisations included the profane middle finger gesture. Mason had just insulted him in the most profound manner, on live television, or so Ed thought. There

had

been a slight ambiguity to what Mason had done; he made so many gestures so rapidly that, if one were predisposed to view them as obscene, a viewer might have interpreted them as such. And Mason had treated Ed irreverently on the air, which alone was enough to anger him. But it was clear to most observers on the set—like Vince Calandra, who later became the show’s talent coordinator—that even at close range, Mason’s gestures were not profane.

After the show, “Ed came over to me and blew his top,” Mason recalled. “He said, ‘Who the fuck are you to use these filthy gestures, you son of a bitch—on national TV!’ ” The showman called him “

a variety of four-, ten-, and eleven-letter words of Anglo-Saxon origin having to do with the subject of sex and perversion.” At first Mason didn’t know what Ed was mad about. The comic had been a rabbi and continued to serve part-time as one until about six months beforehand; by his account, he wasn’t even familiar with the gesture Ed referred to. “A guy who uses that kind of terminology and vulgarity as a way of life on the streets of New York is from a different world than I come from,” he said. Mason tried to explain to the enraged showman that he meant no insult, that Sullivan misinterpreted the gestures, but Ed wouldn’t hear it. “He was too wound up and furious,” the comic recalled. The damage was done. According to Mason, at the end of their encounter Ed bellowed “

I’ll destroy you in show business!” Ed denied having said this.