Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (66 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

Regardless of the veracity of the airport story, this much is true: in early November 1963 the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, was in America on a twofold mission. He wanted to promote Billy J. Kramer, a young rock singer, and he wanted to replicate the Beatles’ European success in the United States. He had major doubts about this latter task. Epstein knew that English bands had never done well in America—and that included the Beatles. The group had released three singles in the United States, with scant success. “She Loves You” had even been played on Dick Clark’s popular

American Bandstand

television show in September 1963, yet the tune had cast not even a shadow on the U.S. charts.

Perhaps now was the time. On October 13, the Beatles had performed on

Val Parnell’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium

, an English variety program that resembled the Sullivan show. With an audience of more than fifteen million, the band’s performance sparked a firestorm of fan interest that London’s

Daily Mirror

dubbed “Beatlemania.” It was this teenage mania that Epstein hoped to spread to the United States.

Peter Prichard, hearing that the Beatles manager sought an American television audience, placed a quick call to Epstein: “

Brian was a friend of mine, and I said, ‘Don’t do anything until you’ve met up with Mr. Sullivan.’ ” Prichard then sent Sullivan a raft of positive reviews of the Beatles’ appearance on

Val Parnell

; he also called Ed and said the group was ripe for their American television debut. (These reviews, in fact, were likely the first news reports that Ed read about the Beatles.)

As Prichard recalled, “Ed asked, ‘What’s the angle?’ ” meaning, how shall we sell this act to the public? “The angle is that these are the first long-haired boys to play before the Queen,” the agent replied. When Ed expressed interest, “I phoned Brian and said, ‘You’ll be getting a call from Mr. Sullivan.’ ”

Sullivan met with Epstein at the Delmonico on November 11. They haggled over whether the Beatles would get top billing; Epstein insisted on it, Sullivan refused—the band was virtually unknown in the United States. However, they managed to strike a deal. The Beatles would appear on February 9, and, betting on a ratings bump from the first show, Ed also booked them for the following Sunday’s show, to be broadcast from Miami’s Deauville Hotel. Additionally, he secured the rights to tape a third performance to be aired at his discretion. The fee was set at $3,500 for each live appearance, plus airfare and hotel, with an additional $3,000 for the taped segment. (The show’s budget ledger indicates that each Beatle was paid $875 for the February 9 show, which came to $515 after taxes.) That was about middling for Sullivan guests at the time; the headliners made $10,000 or more, while many acts made in the $2,500 range.

For Bob Precht, who showed up at the meeting only after negotiations were done, the booking was a source of consternation. He had no problem with the Beatles’ manager; “

Brian was a bright guy—he knew what he wanted,” Precht recalled. However, Ed hadn’t consulted him, as per their arrangement. And, although Bob knew who the Beatles were, he wasn’t sure they warranted a guest shot on

The Ed Sullivan Show.

Ed himself wasn’t too sure. In the second week of December, the

CBS Evening News

ran a report about the Beatles, a short feature produced by one of the network’s London correspondents. Shortly after the broadcast, Ed called CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite, who he was friends with. “

He was excited about the story we had just run on the long-haired British group,” Cronkite said. But Ed didn’t remember the band’s name. “He said, ‘Tell me more about those, what do they call them? Those bugs or whatever they call themselves.’ ” The newsman himself couldn’t remember the group’s name, having to glance at his copy sheet to remind himself. Cronkite told Sullivan he knew nothing about the band, but said he would contact the London correspondent to give Ed more details.

Brian Epstein, having secured the Beatles’ Sullivan debut, launched his promotional assault in earnest. He had convinced Capitol Records to mount a $50,000 ad campaign, including five million “The Beatles Are Coming” stickers—all of which were reportedly affixed to surfaces across the country—and a mountain of “Be a Beatles Booster” buttons, sent to record stores and radio stations nationwide.

On December 17, a disc jockey in Washington D.C. played an advance copy of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” he had gotten from a stewardess friend; it had begun climbing English pop charts in early December. The effect was like fire in dry grass. Radio stations across the country began airing advance copies in heavy rotation. In an attempt to stay ahead of the escalating demand, Capitol Records moved up the U.S. release date from January 13 to December 26. The single began flying off record store shelves the moment it arrived.

As the mania mounted, Jack Paar attempted to steal the thunder from his rival Sullivan.

The New York Times

reported on December 15 that Sullivan would present the English foursome—“Elvis Presley multiplied by four”—in February. Parr saw

his opening. On his January 3 TV broadcast he presented a lengthy clip of the Beatles performing “She Loves You.” Paar made light of the hysteria the group engendered, referring to the screaming girls: “I understand science is working on a cure for this.” Ed was enraged. In his eyes he had paid for an exclusive debut and the contract had been violated. He immediately called Peter Prichard in London, as the agent recalled: “

Ed, as always, had a quick reaction, and said, ‘Tell them if that’s how they’re going to behave, let’s cancel them.’ ” Prichard, however, knew his friend and mentor too well to take immediate action. Instead, he merely waited for what he knew was coming. The very next day, Ed called and said that canceling the Beatles had been “a bit hasty.” Prichard assured Ed the issue had been handled.

Sullivan saw that the Paar clip had only fueled interest in the Beatles. Almost immediately, media coverage began building toward blanket saturation. Seemingly every newspaper and magazine, from

The Washington Post

to

Life

(which ran a six-page spread), began covering the band’s imminent U.S. debut. Countless publications, so recently filled with grim news of the Kennedy assassination, now had something cheery to focus on. And, of course, every Beatles article pointed to

The Ed Sullivan Show.

By January 17, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” hit number one on the Cash Box charts, and by February 1st it sat atop the

Billboard

Hot 100. As the Beatles’ arrival inched closer—and the excitement spiraled ever higher—radio stations started counting down the days and hours to “B-Day.” By the time the band landed at New York’s newly renamed Kennedy International Airport on early Friday afternoon, February 7, hysteria ruled. Some three thousand teenagers (chaperoned by one hundred ten police) clamored to greet them. Describing the crowd, one reporter wrote, “

There were girls, girls, and more girls.” A battalion of two hundred reporters and photographers were on hand, peppering the foursome with queries:

“

Will you sing for us?”

“We need some money first,” John said.

“

Do you hope to get haircuts?”

“We had one yesterday,” George explained.

“Are you a part of a social rebellion against the older generation?”

“It’s a dirty lie,” replied John.

The band’s limousines (one for each Beatle) ferried them to the Plaza, one of the city’s most recherché hotels, which had to endure days of mania. Girls hired taxicabs to deliver them to the front door, explaining to wary doormen that they had rooms there. The hovering crowd sang Beatles songs, or a tune from

Bye Bye Birdie

with changed lyrics: “We love you Beatles, oh yes we do!”

Ed, overjoyed at all the attention, allowed myriad reporters into Saturday’s rehearsal, which he attended, a rarity since Bob Precht normally handled it without him. For one of the band’s sets, set designer Bill Bohnert had created an elaborate backdrop spelling out the name

Beatles.

But Ed, examining it while surrounded by reporters, proclaimed: “

Everybody already knows who the Beatles are, so we won’t use this set.” Because it was the only backdrop Ed had ever vetoed, Bohnert was convinced it was Sullivan’s way of reminding everyone who was in charge.

Vince Calandra, a production assistant, worked with the Beatles as they set up onstage. George Harrison had stayed back at the hotel suffering a high fever, and Calandra took his place during camera setup, wearing a Beatles wig for authenticity.

Vince began chatting with the musicians, and Paul McCartney told him that he and John Lennon had often dreamed of playing the Sullivan show, long before the actual booking. “

McCartney said that he and John were talking on the plane over, and they felt that once they had done

The Ed Sullivan Show

, that was going to be their claim to having made it,” Calandra recalled. As they stood talking, John Lennon asked Vince: “Is this the same stage that Buddy Holly performed on?” To Lennon’s delight, Calandra confirmed that it was.

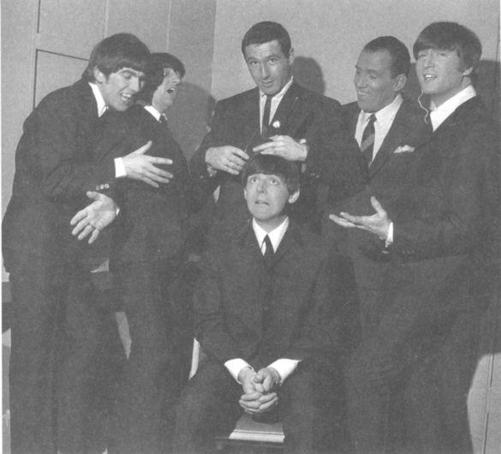

Pretending to give Paul McCartney a much-needed haircut, February 1964. Sullivan was deliriously happy with the ratings the Beatles generated. (CBS Photo Archive)

Getting a ticket to the rehearsal or broadcast was nearly impossible: the show received over fifty thousand requests, so obtaining one required a personal connection with CBS, Capitol Records, or the show’s sponsors. (The night of the performance, a number of girls were caught trying to enter through the air conditioning ducts.) Ed made sure that Jack Paar’s daughter Randy got tickets, which helped remind her father that Sullivan had scored the big scoop. On the other hand, Ed denied requests by three CBS vice presidents—his way of snubbing the management. In the moments before rehearsal the seven hundred twenty-eight-seat theater quivered with anticipation. When a crewmember wheeled Ringo’s drums onstage, the audience experienced

its first moment of near hysteria. Ed gave them a stern lecture on the importance of paying attention to

all

the show’s performers, and he exacted a promise of good behavior from the teenagers.

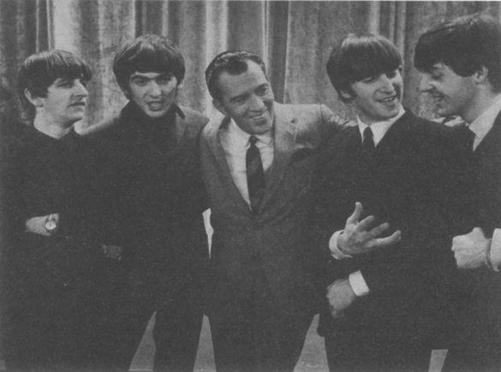

With the Fab Four, February 1964. Their debut performance on the Sullivan show signaled a new era in American popular culture. (Getty Images)

As Ed sat offstage with his unlined pad of paper, preparing his introductory remarks, Brian Epstein approached him. The Beatles’ manager, a master of creating the image of his “boys”—for years they wore matching outfits at his directive—asked to see Sullivan’s remarks about the band. The request was almost comical: a twenty-nine-year-old rock ’n’ roll manager thinking he was going to check Ed’s introductions. “

I would like for you to get lost,” Sullivan said, without looking up.

Almost double

The Ed Sullivan Show

’s usual audience was watching that night as the black-and-white CBS broadcast returned from its first commercial break. Like most of the stage shows Ed had produced since the 1930s, this evening’s program followed the columnist’s rule: to lead with the top item. So the Beatles’ moment had come.