Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (64 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

In

Birdie

, the world that Ed helped wrought is in full flower. The teens all seem brainwashed, thinking with one mind, seemingly zombified by adulation of their rock ’n’ roll hero. The fresh-faced, clean-cut Birdie, an Elvis clone, wears a gold lamé outfit with gold boots, and his singing causes an entire crowd of teens to actually faint with adoration. The movie’s climactic scene, with Birdie-Elvis on

The Ed Sullivan Show

amid wildly enthusiastic teens, is essentially a replay of the real Elvis debut on Sullivan in 1956—but a fully neutered one. Oddly, the movie is a musical

about rock ’n’ roll but its music isn’t Elvis-like. Instead it’s a kind of jazzed up full-orchestra sound reminiscent of Bobby Darin. Even Birdie onstage at the Sullivan show plays only lightly strummed folk music. Apparently the filmmakers were attempting a balancing act similar to Ed’s: they wanted to attract both a teen and an adult audience, without offending either one.

Birdie

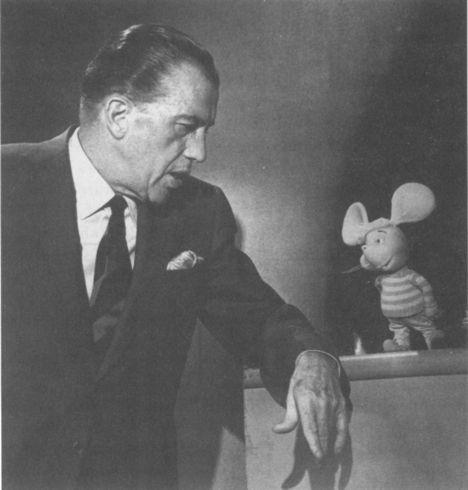

opened in theaters the same month, April 1963, that Topo Gigio debuted on the Sullivan show. A diminutive foam rubber hand puppet, Topo was operated by a team of four Italian puppeteers; he gestured, he danced, his giant ears flopped, his little mouth moved, and he voiced sweet endearments with a loopy Italian accent. Ed, breaking his longstanding rule against taking a lead performance role, developed a routine with Topo. When “The Little Italian Mouse” was a guest, the stage went dark except for a spotlight on Sullivan and the marionette, and the two chatted as confidants, the serious-looking showman leaning in to receive the puppet’s cute replies. They spoke about nothing in particular, yet their tête-à-têtes went on for several minutes. With the Italian puppeteers’ rudimentary English, and Ed’s tendency to fumble his lines, the show’s staff had to be on its toes as the segment veered off script.

Topo revealed an unseen side of Ed. Onstage he operated at a remove, only in rare moments breaking the self-created wall of formality separating him from his audience. But in the Topo segments this wall dissolved. He seemed to lose himself in conversation with the little mouse, chatting intimately with the character as if he were alive. In their affectionate back-and-forth, Ed displayed a vulnerable side of himself that had never been hinted at in his many years of hosting. On its face the Topo—Ed act was a contradiction. Here was Ed, a man whom his critics (and even

friends) had called every variation of stiff, who had cursed and elbowed his way to stardom, burning through an ulcer, yet onstage with Topo he was a sentimental ball of sweetness, being childlike for a live audience of forty million viewers.

With the Italian puppet Topo Gigio in the mid 1960s. The cute puppet was the prop that Sullivan had always wanted to soften his onstage persona. (CBS Photo Archive)

The little mouse was the prop he had always wanted. This was what he sought when he hired Patsy Flick to heckle him in 1948, or booked Will Jordan to mimic him in 1953. Topo opened him up. With the little mouse Ed was anything but Old Stoneface; he was tender and soft. Their segments invariably ended with Topo imploring “Kees-a-me goodnight, Eddie.”

Ed grew to love the little character. He enjoyed the act so much he eventually wore it out; his staff was relieved when he finally quit. He booked Topo an astounding fifty times; only one other act received more bookings (Canadian comedy team Wayne and Schuster, fifty-eight times). Sullivan became so identified with Topo that sometimes as he walked the streets of New York a truck driver would yell out “Kees-a-me goodnight, Eddie!”

It’s likely that part of Ed’s motivation for developing the Topo character was the competition from Disney. With the animator’s show offering the younger set a universe of fantasy and delight, spotlighting the little mouse may have helped parents keep the channel turned to CBS. If Sullivan’s plan was to turn Topo into an irresistible character, he succeeded. The foam rubber puppet became a star in his own right, spawning a legion of little Topo figurines and dolls. The United Nations named him their official “spokesmouse.” In 1965, United film studios released a movie starring the diminutive puppet (in which Topo attempts a trip to the moon), and acquired the rights to make one Topo film a year for the next four years.

In late May 1963, Ed and Sylvia were invited to Manhattan’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel to attend a birthday party for President John Kennedy. The event was a glittering dinner and variety show for six hundred members of the President’s Club, each of whom donated at least $1,000 to the Democratic National Committee. Along with the president and his wife, many of the members of his administration were there: Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, United Nations representative Adlai Stevenson, and Under Secretary of State Averell Harriman.

Ed adored the Kennedys. Other presidents would invite him to the White House; he and Sylvia attended two state dinners hosted by President Johnson, and President Nixon invited the couple to help celebrate Duke Ellington’s seventieth birthday. But these occasions never seemed to matter to him as much as a chance to rub shoulders with the Kennedys. He contributed to JFK’s presidential campaign, and sent a regular stream of birthday notes and letters of encouragement to members of the Kennedy clan. Sullivan was a friend of patriarch Joe Kennedy, who had been a lion of café society in the 1930s; Ed had lauded him in his column for decades. The two men corresponded, and in one letter Ed suggested that musical theater artists Oscar Hammerstein and Moss Hart write speeches for President Kennedy—an idea that Joe Kennedy liked, though it never happened. The elder Kennedy attended Ed and Sylvia’s thirtieth anniversary party in April 1960, and for the event he wrote the couple an affectionate letter that concluded, “

All the Kennedys send you and your family our love.”

Joe Kennedy also sent Sylvia a note in October of that year as the presidential election neared, making reference to Richard Nixon’s problems with makeup in the

recent presidential debates. “

Dear Sylvia, I had read that piece about makeup. I agree with you—how many more excuses can they find? Incidentally, things are getting better every day. Sincerely, Joe.” In April 1962, Ed sent a letter to Joe Kennedy in which he enthused, “

I think that your brilliant young son has wrapped up another term in the White House as a result of his quick and determined handling of Steel.… Poor Nixon is in a helluva spot. Now he can write another book and add an additional ‘crisis.’ ”

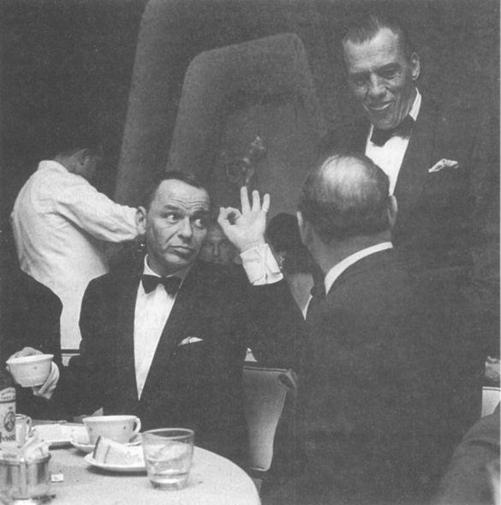

Old Blue Eyes and Old Stoneface, at the Eden Roc nightclub, Florida, 1964. The longtime friendship between the two men boiled over into a bitter squabble in the mid 1950s, though Sinatra later made a peace overture. (Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

President Kennedy, in March 1961, sent a short letter to Sullivan agreeing to tape a promotional message Ed had requested, for an event that encouraged international understanding. The letter from Kennedy was typed and addressed “Dear Mr. Sullivan” but the president scratched out “Mr. Sullivan” and wrote in “Ed.” “

The idea for your International Assembly sounds most interesting and it is certainly a much-needed

effort in the field of international communications,” Kennedy wrote. “I would be happy to prepare a taped message for your first Assembly.”

In later years, Ed contributed to the Kennedy Library, and received letters of thanks from Ted Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Jacqueline Kennedy. Ted Kennedy’s wife Joan sent Ed a thank-you note in July 1964 with an added postscript: “

P.S. Ted and I watch your wonderful show every week and enjoy it so much.”

Given his feelings of affection for the Kennedys, it was no surprise that Ed found the birthday party for President Kennedy in late May 1963 to be a magical evening. He called it one of the “

unforgettable moments” in his many years of outings with Sylvia. Despite its elegance, there was a touch of informality to the evening—the ballroom contained no dais or head table, and the president circulated through the crowd, reportedly shaking hands with almost all the guests. The Waldorf-Astoria had been transformed for the event. A top Broadway lighting specialist, Abe Feder, designed a display to make the hotel’s lobby resemble a palace entryway. The stage was set up as a theater in the round, built around a “Circle of Life” display in the ballroom’s floor. In his keynote speech, Kennedy described the Democrats as “

the party of hope,” and, referencing the many Broadway and Hollywood attendees, said that it was natural that performers “should find themselves at home in the party of hope.”

Although Ed was often tapped to emcee high-profile events, for this evening he was invited as a performer. The program’s variety show was produced by Alan Jay Lerner, who wrote the book and lyrics to the Broadway shows

My Fair Lady

and

Camelot

; Ed had done a tribute show dedicated to Lerner two year earlier. Ann-Margret, who had appeared with Ed in

Bye Bye Birdie

, sang “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home,” and Jimmy Durante, who Ed had known since his speakeasy days in the 1920s, donned a Kennedy wig and crooned “Start Off Each Day with a Smile.” Bob Newhart, a Sullivan regular, performed a stand-up routine satirizing television and the tobacco industry. For the finale, Mitch Miller entered with an eleven-man chorus singing “Together.” Ed was part of the chorus, along with Henry Fonda, Eddie Fisher, Robert Preston, Van Johnson, Peter Lawford, Mel Ferrer, Tony Randall, Donald O’Connor, David Susskind, and Bobby Darin. Henry Fonda surprised everyone by launching into a quick-step tap dance, later confiding to Ed, “

I used to be a member of Chorus Equity.” Following the chorus onstage was Louis Armstrong, singing “When the Saints Go Marching In,” after which Audrey Hepburn sang “Happy Birthday.”

However festive, the party at the Waldorf-Astoria was to be the president’s last birthday. When the charismatic Kennedy was assassinated while touring Dallas in a motorcade seven months later, it threw the country into a shocked state of mourning. For days, television coverage of the tragedy was nonstop; the Sullivan show on November 24, just two days after the event, was preempted. Earlier that day, Jack Ruby had shot and killed Kennedy’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, as he was being transported to a nearby jail.

The following week, Sullivan grappled with how to put on a variety show in a period of national mourning. After extended discussion, he decided to host a show with no comedy. Then, just days later, he reversed himself. He had negotiated with impresario Sol Hurok, who had brought Russia’s Obratsov Puppet Theatre to the United States, for the rights to present a full-hour program of the puppets. A show for the kids seemed appropriate.

The Obratsov puppet show was a lighthearted affair, though Ed appeared to take no joy in it. At the beginning of the hour, with his always-grave face now looking almost funereal, he announced that he was presenting the puppet program as a tonic for “

the nightmare week we’ve been through.” The look on his face that evening was like a headline: the country had fallen into a deep grief, an innate somberness that it seemed nothing could revive. As the calendar inched toward 1964, the gray national mood felt as if it would stretch into the foreseeable future. Was there nothing that could lift America’s spirits?