Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (78 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

Still, despite his deepening depression, Sullivan might surprise his grandson with flashes of his former spirit. On one occasion during these months, Rob was walking Ed home late in the evening, going up Park Avenue toward the Delmonico, when he spotted two figures walking toward them who were obviously prostitutes, dressed in tight miniskirts and high heels. Rob felt a twinge of anxiety as they approached, thinking, “I hope they don’t recognize him and start to engage him in conversation—he’s frail, and sad, and I want to spare him any inconvenience.” But as the ladies neared, it was Ed himself who decided to say hello, bellowing out

“Hello, girls, how are you?”

The women were momentarily startled, then seemed to realize who he was, at which point Rob guided his grandfather by the elbow toward home.

In May 1974, Sullivan was hospitalized for a problem related to his long-standing ulcer condition. He was released at the end of the month with instructions to come back for daily visits. However, he began skipping visits, making it in perhaps once a week. That summer, having spent very little time in churches throughout his life, Ed was seen praying at St. Malachy’s Church in midtown.

On September 6, an X-ray revealed bad news. Sullivan’s doctor checked him into Lenox Hill hospital and called his family, who decided not to tell him the full nature

of his illness. Ed had inoperable cancer of the esophagus, and his doctor told his family that he wasn’t expected to live much longer. “

We had consulted with his doctors and it was felt that if he were told the truth, it would severely dampen his spirits and make him totally depressed,” Bob Precht said. “It was best he didn’t know. Right up until the day he died, his spirits were fine and he believed he was going to get well.”

He spent five weeks in the hospital. Bob and Betty visited regularly, and Carmine Santullo was there constantly. On September 28, his seventy-third birthday, he was given two parties: one by the nurses, relishing their celebrity guest; the other by his family, at which he ate cake and ice cream and talked about looking forward to getting back to work. In fact he hadn’t left work. He continued to write his column from his hospital bed, piecing together

Little Old New York

from press releases delivered by Carmine.

On the afternoon of October 13 his doctor called the Prechts; Ed’s condition had worsened dramatically. They immediately drove to the hospital, sitting at his bedside while he lay unconscious. At 7:30

P.M.

, when Carmine arrived, they left. Carmine sat with him through the evening as Ed remained unconscious.

It was a Sunday night. Since 1948 he had lived for Sunday nights, and now he was dying on one. But not until the show was over. Shortly after 10

P.M.

, as the evening’s program would have been finished, and Sylvia would have been picking him up for dinner at Danny’s Hideaway, he stopped breathing.

The funeral, on October 16, was a celebrity affair. Held on a rainy autumnal day, with some three thousand people crowded into and right outside of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the event drew both mourners and those seeking a glimpse of the famous. The crowd outside, most carrying black umbrellas, watched a long line of limousines deliver entertainment, sports, and political figures to the front door. Cardinal Cooke led the service, and the attendees included Mayor Abe Beame, former Mayor John Lindsay, Attorney General Louis Lefkowitz, restaurateur Toots Shor, boxer Jack Dempsey, vaudevillian Peg Leg Bates, comedian Rodney Dangerfield, and Metropolitan Opera star Rise Stevens. Classical pianist Van Cliburn praised Sullivan for his “

faithfulness to the serious arts.” CBS head Bill Paley called the showman “

an American landmark.” Walter Cronkite, who first met Sullivan before World War II, said, “

Ed had a remarkable quality of toughness in pursuing what he saw as right. He was an Irish grabber and I think that’s admirable.”

Ed had updated his will in March 1973. He left virtually all of his estate to Betty, with $10,000 going to Carmine, and a smaller amount left to his siblings. He noted in his will that he made no bequest to charity because he had done so much for charitable concerns during his life. He was buried next to Sylvia in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.

The day after he died, the

Daily News

printed Ed’s last column, which he had written in his final days at Lenox Hill hospital. He composed that edition’s

Little Old New York

much as he had written the column for the last forty-two years, using a series of ellipses to connect disparate items, one bit flowing into another, a stylistic invention

he borrowed from Walter Winchell in the early 1930s. Because he believed he would soon leave the hospital, the column was its usual all-inclusive mix, spotlighting events across myriad fields:

“Bennett Cerf’s widow, Phyllis, partied [

sic

] Sinatra after Garden blockbuster … Mia Farrow okay after appendectomy … Richard Zanuck and Linda Harrison derailed … French President Giscard d’Estaing holds press conference on 24th to outline France’s policy in foreign affairs … Dionne Warwick packing Chicago’s Mill Run theater…

President Ford’s ex-press sec’y, J.F. TerHorst, guest speaker at Nat’l Academy of TV luncheon at Plaza on Thursday … Hal (“Candide”) Prince’s backers got another $217,500 from his three hits: “Fiddler,” “Cabaret,” and “Night Music”…David Frost and Lady Jane Wellesley a London duet … Nirvana Discotheque, a $250,000 shipwreck, to reopen as Nirvana East restaurant … The Jimmy (Stage Deli) Richters’ fifth ann’y … Cardinal Cooke presents special awards to couples married 50 years, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Jan. 12 …”

The tidbits flowed continuously, seemingly without end, providing something for everyone in a rapidly moving one-column parade. Ed was gone, but

Little Old New York

, as it always had, kept bustling on.

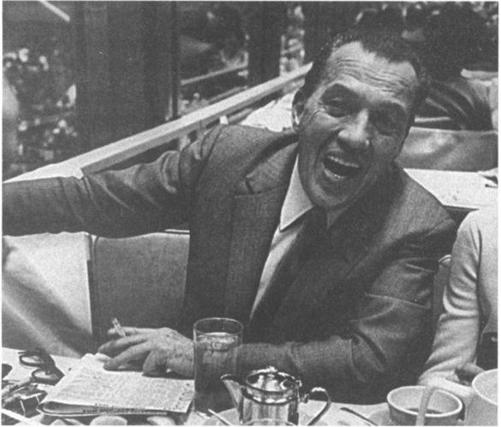

At Yonkers Raceway, 1967. (Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Epilogue

F

AME IS WHAT

E

DWARD

V

INCENT

S

ULLIVAN DESIRED

, and fame is what he achieved. In his lifetime, there were few public figures who spent as many hours in as many American living rooms as Ed Sullivan. He was known, and in many cases revered, by the tens of millions of almost ritualistic viewers who gathered each Sunday to watch his weekly circus. He is forever memorialized as the monochromatic purveyor of a wildly polychromatic mélange, a graven-faced emcee who turned hosting a lively showcase of high and low art into a remarkably sober task. That this compressed icon of Ed Sullivan bore only nominal resemblance to the flesh-and-blood Ed Sullivan is of little import. Certainly, the vituperative, epithet-hurling Stork Club habitué, the Fidel Castro interviewer and earnest blacklisted the rock ’n’ roll patron saint and strict moralist, the producer who was tyrannical and sentimental, shrewd and irrational, petty and generous, was only glimpsed at moments on screen. But no matter. He is stored for the millennia with his name atop the marquee, as he so hungered for.

Reruns and retrospectives of

The Ed Sullivan Show

—his beloved creation that he placed at the center of his life—have continued to fuel that fame. The show has never fully gone off the air. After cancellation of its original run in 1971, it became a bottomless source of clips, the ultimate trove for television and documentary producers. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Ed was seen swinging his right arm and pointing to any number of acts. In 1980, a “Best of Sullivan” series appeared in syndication, broadcasting edited thirty-minute versions of the one-hour show periodically throughout the decade.

The showman’s return to major network success came on February 17, 1991, in a broadcast, appropriately, on CBS on Sunday night. The program was produced by Andrew Solt, a television and film producer who had often mined the Sullivan show for clips, and who bought the complete library from the Sullivan family in 1990. Called

The Very Best of Ed Sullivan

, the two-hour show was a decisive ratings victory for the network. It was the second-highest-rated program for the week, and helped CBS win the February sweeps for the first time since 1985. The network commissioned three more retrospectives, each of which was a Nielsen booster.

Solt also produced a series of one hundred thirty half-hour Sullivan shows, which went into syndication in various outlets, including

Ed Sullivan’s Rock ’n’ Roll Classics

, played on the cable channel VH1, and a “Best of” program shown on the TV Land cable channel. PBS stations began airing Sullivan shows in 2001, typically on Saturday nights, broadcasting them regularly until 2004. Additionally, Solt produced a series of DVDs, including

The Best of Broadway Musicals, Unforgettable Performances

, and

Rock ’n’ Roll Forever.

Bootleg copies of the show do a healthy trade: Sullivania is sold continuously on eBay, further distributing not just show tapes but also photos of Ed with performers, ticket stubs, and, occasionally, odd items like a plaque awarded to the showman in the late 1960s.