Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (68 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

Ed came on and told the audience an impressive bit of fiction: “The greatest thrill for the Beatles—and we got a big kick out of it—is the fact that they were actually going to meet Mitzi Gaynor tonight on our show.” If his intent was to make the Beatles appear as typical starstruck youth, he succeeded with at least part of the studio audience, who sighed appreciatively. But the idea that the foursome was eager to meet the milquetoast star of light musicals was patently absurd. Still feeling chipper, Ed interrupted himself to check his microphone. “Is this off, too?” he asked, glancing up at the microphone above him. Getting no answer, he muttered “Communists!” which prompted a reflexive laugh from the audience.

The showman presented a taped segment from Miami’s Hialeah Race Track in which a four-person acrobatic troupe named the Nerveless Nocks swayed on one-hundred-foot poles while performing tricks—“One of them almost lost their life doing that,” Ed reported. The live broadcast resumed as Sullivan brought on comic Myron Cohen, whose routine was pure Borscht Belt. (“A priest, a minister, and a rabbi are playing cards …”)

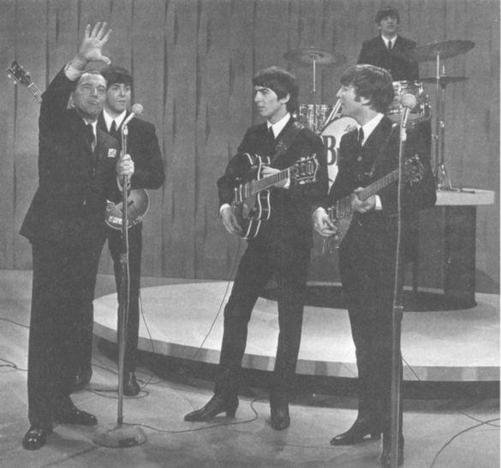

When Ed reintroduced the Beatles for their final set, he attempted a joke based on their song titles. In two weeks, boxer Sonny Liston would face Cassius Clay (soon to change his name to Muhammad Ali). “Sonny Liston, some of these songs could fit you in your fight—one song is ‘From Me to You.’ And another one could fit Cassius, because that song is ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand.’ ” The attempt at humor fell like a dull thud, though the audience offered a polite chuckle. Then: “Ladies and gentlemen,

here are the Beatles!”

The energized quartet launched into an exuberant “I Saw Her Standing There,” in which John had to stoop to reach his too-low mike stand, but it didn’t seem to matter—the band was in rollicking good spirits, bouncing up and down as they strummed. John and Paul howled in unison at the verse’s end to set up a guitar solo by George. They stopped just long enough for Paul to count off—“One! Two! Three!”—before jumping into a fast take of “From Me to You.” To introduce their last number, Paul made his own attempt at humor: “This is one that was recorded by our favorite American group, Sophie Tucker.” The audience didn’t get the cheeky humor; was an eighty-year-old vaudevillian really this rock ’n’ roller’s favorite band? (The joke went over well in England, where audiences understood that Paul meant that the large-sized Tucker was big enough to be called a group.) The crowd’s silent response was interrupted by a single man laughing, very loud, continuing to guffaw through the first guitar strums; it sounded like Sullivan, who doubtless found the notion amusing. Then the band delivered “I Want to Hold Your Hand” as a dose of fun-loving sunshine, galloping through verse and chorus like the tune was happiness itself.

As the audience wailed and cheered, the Beatles walked over to Ed, who told them—and here Ed was addressing older viewers at home: “Richard Rodgers, one of America’s greatest composers, wanted to congratulate you, and tell the four of you that he is one of your most rabid fans. And that goes for me, too. Let’s have a fine hand for these fellows!”

A few days later, Ed and Bob Precht hosted a dinner for the Beatles and the staff, partially as a perk for the staff; their reward for working hard was an opportunity to mingle with the band. The musicians split up to sit at different tables, so all of the fifteen or so staff members had a chance to say hello. Over the course of the evening the crew found the foursome thoroughly charming. One of the secretaries remarked

that Ringo felt a touch of melancholy because, having enjoyed himself so profoundly on his first American trip, he observed, “

This was the best it was ever going to be—it could never get better than this.”

The Beatles on the Sullivan show, February 1964. Sullivan attempted to quiet the crowd, which was hardly possible. (CBS Photo Archive)

Ed had bestowed the Sullivan seal of approval on the new rock ’n’ roll sensation, and that, initially at least, appeared to be a safe bet. Within sixty days the Beatles held the top five spots on the

Billboard

Hot 100, with fourteen of their hits in the top one hundred chart positions, two feats that have never been topped. The band’s third Sullivan appearance on February 23 provided still another ratings jolt, though not as dramatic as the first two evenings. This third Beatles performance was taped the afternoon of their debut, and edited together with a show taped in front of a live audience to present the illusion of a live performance. Ed even recorded introductions suggesting the Beatles were live: “You know, we discussed it today, we’re all gonna miss them. They’re a nice bunch of kids.” (Additionally, in the spring of 1964, Ed flew to London to interview the Beatles on the set of

A Hard Day’s Night

,

and presented this segment during a May broadcast.) The publicity value of the Beatles appearances was incalculable, as legions of reporters and television crews trailed the band’s every move during their first American trip, with all the reports mentioning the Sullivan show. The Beatles broadcasts and the attendant tidal wave of publicity boosted

The Ed Sullivan Show

’s ratings enough to make it the 1963–64 television season’s eighth-ranked show.

The meeting of these two major entities, the life force of the Beatles with the national institution that was

The Ed Sullivan Show

, produced some kind of cultural fission, an inestimable spark of change, a sense that the season had turned irrevocably. It was all anybody was talking about. If Ed had always dreamed of fame, in these weeks he entered a stratosphere of cultural primacy that even he had never imagined. The showman basked in his glory.

Dissenters, however, sat unhappily in living rooms across America. Their apprehension was only partially voiced by the critics, who reviewed the Beatles’ Sullivan debut as if it were slightly rotten fruit. The

New York Times

reviewer, who compared the Beatles’ haircuts to that of children’s show host Captain Kangaroo, and who referred to Ed as “the chaperone of the year,” observed that, “

In their sophisticated understanding that the life of a fad depends on the performance of the audience, and not on the stage, the Beatles were decidedly effective.” Joining the chorus,

The Washington Post

’s critic opined that the musicians were “

imported hillbillies who look like sheepdogs and sound like alley cats in agony.” Critics, however, were a group that Ed had always succeeded in spite of; it was the home audience he worried about, and he understood that a deep sense of unease hid beneath the mostly bemused reviewers’ barbs.

For some, the Beatles were a novelty; for others, of course, the group was as thrilling as anything they had ever seen. For another segment, however, the fast music, the long hair, the out-of-control teens—it all made them distinctly uncomfortable. “

I was offended by the long hair,” recalled Walter Cronkite, who represented the voice of mainstream America as much as anyone. “Their music did not appeal to me either.” Part of Ed’s nearly flawless sense of the public’s taste was his deep reverence for—even wariness toward—conservative values. He was, after all, helping to create the status quo. He decided which artists and entertainers performed live for his massive national audience, which performers received the hallowed Sullivan imprimatur of acceptability. This was a delicate balancing act since survival meant entertaining everyone while offending no one.

Sullivan’s cautious, stolid nature worked in his favor in this regard. He had never wanted to be a leader, never wanted to take the public where it wasn’t ready to go. To keep the show in a dominant position he had to walk in lockstep, or just a step ahead, with a fickle public. Any move toward change had to be made carefully. His most precious talent was his ability to sense audience desire and to gratify that desire. The Beatles booking demonstrated that Sullivan the producer—the global talent scout—continued to have an unerring nose for ratings gold. But was his audience the unified entity it always had been?

Elvis, seven years earlier, had prompted a major backlash, with angry letter writers decrying what they saw as the singer’s corrupting influence on youth. Yet while Presley turned the pop song into a vehicle for rambunctious sexuality, ultimately he was a nice boy with an “aw shucks” quality, who used his royalties to buy a new

house for his parents. The Beatles were something else. All those teens in near riot—they actually required police to contain them—whatever this was about, it wasn’t about deep reverence for conservative values. When the New York press corps greeting the Beatles at the airport had asked, “Are you part of a social rebellion against the older generation?” it had been a serious question. And social rebellion was not part of what had allowed Sullivan to outlast the competition since 1948.

The Reverend Billy Graham, who had violated his rule against television on the Sabbath to watch the Beatles, seemed to speak for some of Sullivan’s audience. The band was a symptom of “

the uncertainty of the times and the confusion about us,” he said. The problem for those viewers who felt as Graham did was that the show would soon take on a new tone. Spurred by the Beatles ratings spike, by the spring of 1964 Sullivan was booking a plethora of rock acts, changing the program in ways that many found disturbing. “Frequent appearances of rock ’n’ roll groups on

The Ed Sullivan Show

have turned the show into a teenage attraction that creates problems for the producers and the Columbia Broadcasting System,” reported

The New York Times.

The problem was the teenagers themselves. Something had changed; the teens visiting the Sullivan show “

set up an hour-long din that distracts other performers and mars the audio portion of the show.” In response, the show stopped admitting anyone under age 16 unless accompanied by a parent. That was one solution, but a reporter—surely echoing what many parents hoped—suggested another: couldn’t the show just stop booking rock ’n’ roll?

“

That’s a possibility,” Bob Precht said, “but we feel strongly that rock ’n’ roll is part of the entertainment scene. Such groups are selling records like mad. We can’t ignore an important trend in our business. We don’t want to be a rock ’n’ roll show, but there is value in having youngsters watch our show.” In other words,

The Ed Sullivan Show

was trying to have it both ways, to satisfy two audiences—teens and their parents—who now wanted very different things. The “Big Tent” was being stretched further than ever before.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN The Generation Gap

The Generation Gap

H

AVING OPENED

P

ANDORA’S

B

OX WITH THE

B

EATLES

, Ed launched the 1964–65 season with the full fury of twanging guitars and pounding drums. He had featured the new sound in his mix since Elvis’ debut in 1956, but now it was pushed center stage. Almost every show featured a new rock band. Headlining the season opener were The Beach Boys singing “I Get Around” in a set decorated with vintage roadsters. In October, Ed presented a very fresh-faced version of the Rolling Stones who, eyeing the titanic success of the Beatles’ Sullivan debut, were eager to follow. “

We got it into our heads that Ed Sullivan was the thing to do—the only thing worth doing,” said Stones pianist Ian Stewart. The group’s performance of “Time Is on My Side” and “Around and Around” served a dual purpose: it lifted Sullivan’s ratings, and it helped the band sell more than $1 million in concert tickets that fall. Ed, however, was horrified by them. In contrast to the Beatles, who were cheery and had worn matching outfits, the Stones were sulky bad boys and, in Ed’s view, thoroughly unkempt. He declared he would never book them again.