Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (72 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

The band balked, but Ed issued his standard ultimatum: “

Either the song goes, or you go.” The Stones reluctantly acceded. By the time the group played the song for dress rehearsal, the directive had been stressed to lead singer Mick Jagger repeatedly, to the point where he was getting angry. When the CBS Standards and Practices representative arrived, he needed to witness Jagger being told to change the lyric, but he didn’t want to approach the band himself. So the task was given to talent coordinator Vince Calandra, who dutifully walked up onstage and told the singer, once again, that he needed to change the lyric. “

Fuck off, mate,” Jagger said, as Calandra recalled. During the broadcast, the Stones singer performed as requested but briefly rolled his eyes upward to theatrically mime his protest.

As was now expected, Sullivan again this season presented all the latest bands in the suddenly exploding pop-rock scene. The Mamas and the Papas harmonized on “California Dreamin’ ” and the Lovin’ Spoonful, performing in front of a spinning kaleidoscope backdrop, sang “Do You Believe in Magic.” Paul Revere and the Raiders romped through “Kicks,” the Turtles rendered their number one hit “Happy Together,” and the Young Rascals performed “Lonely Too Long.” Many of the groups from the last few years returned, most notably the Beatles, who offered a taped performance of “Penny Lane” and the psychedelic “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

Although rock ’n’ roll was now a central element in the show, it had reached a saturation point. Sullivan and Precht would not allow the new sound to take up yet more program time. If anything, the two producers retreated somewhat from rock in 1966–67, usually booking no more than one band in an evening. This left ample time for traditional acts. Over the course of the season, Jack Benny did stand-up, Henny Youngman tossed out one-liners, and sketch comedy team Wayne and Schuster made three of their fifty-eight appearances. The Woody Herman Orchestra accompanied velvety vocalist Mel Tormé on “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” Bandleader Xavier Cugat, who was a strolling violinist at the Casa Lopez nightclub the night that Ed met Sylvia there, jumped through “Tequila.” The U.S. Marine Silent Drill Team displayed their precision maneuvers, as did the show’s never-ending stream of jugglers, contortionists, and acrobats. The Sullivan show, or so it seemed, could balance its offering for all audiences just as it always had.

The program’s emphasis on high art had lessened greatly—it was not a ratings winner. With rock ’n’ roll now taking up a hefty percentage of airtime, something

had to be cut, and the stage plays and classical musicians so frequent in the 1950s fell victim. Still, there continued to be at least a token nod to fine art. In December, the Berlin Mozart Choir performed, and a month later dancers Edward Villella and Patricia McBride of the New York City Ballet performed a pas de deux from Asafieff’s

Flames of Paris.

Ballerina Sandra Balesti floated through a solo, though her accompaniment was a Rodgers and Hammerstein medley.

From a ratings standpoint, the updated Sullivan show remained a hardy perennial. As the 1966–67 season ended—Sullivan’s nineteenth year on the air—

The Ed Sullivan Show

was television’s thirteenth-ranked program, and continued to win its time slot. It was the longest-running prime-time show, and its ratings verified it was as much an institution as a television show.

Mellow. That was a word that had never been used to describe Ed Sullivan. In the reams of newsprint that the New York press had churned out about the showman since the late 1940s, never once had that descriptive been employed. However, as the mid 1960s turned toward the late 1960s, Ed demonstrated that even Irish whiskey could lose its edge.

“

I remember once I came in to talk with him and he was taking a nap—and I thought, that’s crazy,” recalled comic Joan Rivers, a regular in this period. The naps between dress rehearsal and broadcast—which never happened in earlier years—had

become a weekly occurrence. The personal secretaries who worked with him in these years all remembered him as a kind, gentle man who rarely raised his voice, though they had heard tales of the Sullivan temper. “

He was always very nice to me,” recalled Barbara Gallagher, a production assistant who worked closely with Ed in the mid to late 1960s. “He would tease me—‘Hey legs, how you doing?’ ” She knew he ran a “tight ship” in previous years, yet now “he became more docile, more introspective.” The show seemed to bustle around him, as the veteran crew went about its work like a well-tuned machine, guided by Bob Precht.

Chatting with Joan Rivers, 1966. “If he put his arm around you, you knew you had made it,” recalled Rivers. “The power he had was enormous.” (CBS Photo Archive)

Vinna Foote, a production assistant in the late 1960s, remembered Ed calling her to join him at the neighborhood restaurant he ate at before airtime, ostensibly to make last-minute changes. But he had no changes to make. “

A couple times he had me come over, he just wanted me to have a drink with him.” She declined the drink, but sat and talked with him as he had his customary preshow Dubonnet liquor with Sweet ‘n Low. “He never chased me around or anything—he was lonely, he was a lonely person.”

Ed’s forgetfulness and mental confusion were becoming more pronounced. “You knew there was a really sharp guy at home somewhere, but he wasn’t showing it as much,” recalled production assistant Jim Russek. “Because he wasn’t as in the loop as much as he was in earlier years, that was frustrating to him, and he was capable of lashing out at people when he felt out of control.” One Sunday evening, Ed came down from his nap about an hour before showtime, mistakenly thinking it was just minutes before broadcast. “He started screaming, ‘Where the hell is everybody?—We’ve got a show to do!—Why am I the only one standing here?’ ” After a few moments of yelling, Russek explained to him, “Sir, it’s quarter to seven.” After the show Ed and the staff had a laugh about it.

In June 1967, he considered plastic surgery; his baggy eyes were beginning to give him a haggard look. He set up an appointment and went to the doctor’s office, sitting in the waiting room. After a while he got up and took a walk, then decided to skip surgery. Ed would be Ed, unvarnished as always.

That same June, in an interview with

Ladies Home Journal

, he had kind words for, of all people, Walter Winchell. Walter “

invented the Broadway column and wrote it better than anybody else,” Ed said. He conceded something that had long bedeviled him in earlier decades: “Any columnist had to run in his shadow. Me included.… No matter which way I turned, there was Winchell in my way.” Ed even offered an olive branch: “Winchell and I haven’t spoken to each other in years. But I wish we’d continue to be friends.” His assessment of Winchell’s earlier power was accurate, yet the younger Ed Sullivan had been loathe to acknowledge it. Never in his many years of snarling at Walter had he admitted he was envious of the hugely famous columnist.

Several weeks later the former archrivals both happened to be having dinner at Dinty Moore’s restaurant. Ed was dining with Sylvia; Winchell was dining with Dorothy Moore, the executive secretary of the Runyon Fund, a cancer research fund he founded after the death of writer Damon Runyon. Walter, by 1967, had hit bottom. His influential radio show was long gone and his column’s distribution had dwindled to the vanishing point. (In desperation, he began visiting the El Morocco nightclub and handing out mimeographed copies of his column.) Perhaps due to his lessened circumstances, Ed’s kind comments in

Ladies Home Journal

meant all the

more to him. Seeing Ed across the room, Walter got up and said hello. He greeted Sullivan warmly and Ed reciprocated. Suddenly, they were chums. The decades spent cursing at each other, glaring at one another at the Stork, faded away. Walter invited Ed to join the board of the Runyon Fund, which Ed accepted. The two made a date to meet later that week for cocktails at El Morocco. Either by coincidence or invitation, onetime

Graphic

columnist Louis Sobol also showed up at the nightclub. The trio had a photo snapped: three smiling newspapermen, three old friends.

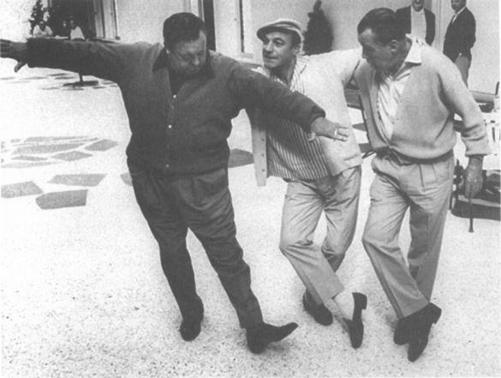

From left, Jackie Gleason, Gene Kelly, Sullivan. When Sullivan visited the set of Jackie Gleason’s TV show in January 1967, the three men goofed through an impromptu tap dance. In the late 1940s, Sullivan introduced Jackie Gleason to the television audience. (Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

In Sullivan’s September 10 broadcast, he introduced Winchell from the audience. Ed, momentarily confused, referred to Walter as a sports star, an introduction meant for football hero Frank Gifford, also in the audience. He then found his place in the cue cards and touted Walter as the “daddy of the Broadway columnists.” (In that same show, featuring the rock group the Young Rascals, the girls in the audience screamed so much that Ed yelled, with a smile, “Quiet or I’ll thrash you!” proving he hadn’t turned into complete butterscotch.)

A year later the Friars honored Sullivan for his twentieth year on the air; at the ceremony Walter sat up on the dais with Ed. In his speech, Winchell spoke glowingly of his former rival: “

As we both grew older, we found that we were citizens of a kingdom more beautiful than Camelot. Not a never-never land, but a very real and magic place called Broadway. Ed Sullivan is as much a part of Broadway as Times

Square, Dinty Moore’s, Toots Shor’s, Lindy’s, Max’s Stage Deli,

Variety.

…” As the evening concluded, Ed shook Walter’s hand and said, “

Walter, don’t ever let thirty-five years separate us again.”

The 1967–68 season opened with a scream. Headlining the September 17 show were The Doors, who in July had hit the charts for the first time—at number one—with “Light My Fire.” If ever a group was guaranteed to draw extra scrutiny from the CBS Standards and Practices department, it was this pioneering psychedelic rock band fronted by Jim Morrison, who wore skintight leather pants and performed as if gripped by a hallucinatory frenzy. He earned the nickname the Lizard King, a phrase from one of his rambling, incantatory poems, for his grand and otherworldly approach to life.