Dickinson's Misery (38 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

Precisely because women are sheltered from “business and politics” they may “retrieve” the spirit of the age; precisely because of the antithetical relation of “feminine genius” to “profit” and the consolidation of “power” it becomes an ideal (even sacred) sign for artistic profit and cultural power. We might recall here William Dean Howells's later remark on Dickinson: “this poetry is as characteristic of our life as our business enterprise, our political turmoil, our demagogism, our millionarism.”

24

The woman poet is the perfect vehicle for cultural transference. We recall that Higginson put the logic succinctly in an 1871 essay on Sappho: “The aspirations of modern life culminate, like the greatest of modern poems, in the elevation of womanhood.

Die ewige Weibliche zieht uns hinan.

”

25

Given Griswold's earlier remarks in the same preface on the several ways in which “we are in danger” of crediting as genius a woman's poetry that may be “only the exuberance of âfeelings unemployed,'” and given that Higginson's essay on Sappho consists almost entirely of an elaborate defense of Sappho's art from charges of suicidal self-pity and lesbianism, it is not hard to see that the period's discomfiture with feminine lyric sentimental excess was only one half of a dimorphism, or two distinct forms of the same parts. Those parts fused at one level into the figure of a woman poet who was dangerously and deceptively testimonial; at the other, they combined to form the flower of civilization, of tradition. The value of the latter was guaranteed by the “unhealthy” presence of the former.

In the terms of the Dickinson lines with which we began, the period's nagging question was how to turn the indelible pattern of feminized personal suffering into “the Goods / of Day” (Bowles's “priceless gifts to the world of literature and art”). In Dickinson's lines, the charm and delight (to use Arnold's words) of Morning's artistic representation cannot be extricated from the determining pain of personal experience; the subject of Dickinson's poem cannot, as Bowles would have it, put the distorting affect of the “first intensity” of grief behind her. Instead, midnight collapses into dawn, suffering into representation, morbid reaction into diurnal action, and self into text: “Misery, how fair.” The line that hovers grammatically

over Dickinson's lines derives part of its rhetorical force from its very Dickinsonian condensation of two aspects of the cultural situation of nineteenth-century women's sentimental lyric, a situation that still informs modern critical reading.

HIS

C

HASM

”

The attempt to lift subjective representation free of the perspectival limitations of the merely personal, to lift it away from the tangle of gendered and sexualized interest, to elevate it from the basis of a primitive or natural to the transcendence of an aesthetically crafted performance is also the desire to extricate first-person expression from the referential claims of singular bodies. Again and again, Griswold's, Hamilton's, Arnold's, and Bowles's accounts of the vexed relation between personal and literary identity circle back to the question of bodily identity and its discontents. Karen Sanchez-Eppler has argued that “the extent to which the condition of the human body designates identity is a question of [antebellum] American culture and consciousness as well as politics, and so it is a question whose answers can be sought not only in political speeches but also in a variety of more ostensibly aesthetic forms, from sentimental fiction and personal narratives to those conventionally most ahistorical of texts, lyric poems.”

26

The “question,” as Sanchez-Eppler sees it, is embedded in abolitionist and feminist rhetoric of the period, but also in the “radical privacy” of Dickinson's lyrics, which “lay bare the contradictory connections between embodiment and representation.”

27

In view of our entrance into the conversation surrounding such contradictory connections in the sentimental lyric, we might extend Sanchez-Eppler's view to include the scope of the identity politics at stake in both the writing and reading of the lyric, and especially to include what I will argue is sentimental poetry's stress on an unrepresentable embodiment, on a historicity threatened by the elevating aims of figuration. Thus the “misery” in “the literature of misery” may be a symptom less of the experiences of “poor, lonely and unhappy” women than of the rhetorical difficulty of pointing to an experience (or an identity) before it becomes a metaphor. On this view, the “ahistorical” situation of the lyricâits association with extreme privacy as well as it aspiration to the more than merely

personal

âis exactly the problem for writers of sentimental verse. It is also, as I have argued in previous chapters, a central problem for Dickinson. Not only does her exposure of “the contradictory connections between embodiment and representation” affiliate her work with the currents of mid-nineteenth-century discourses on identity, but Dickinson's emphasis

on the material trace of written (and unwritten) intention may itself be traced past the modern idealization of Dickinson's lyric voice to a moment at which the gendered (that is, bodily) cost of such an idealization was very much at issue. Thus my contention in the previous chapter that “the materiality of writing ends by substantiating the claims of a body historically subject to the inversions (and perversions) of reading” may now be placed within a lyric discourse that brought specific pressures to bear on such claims.

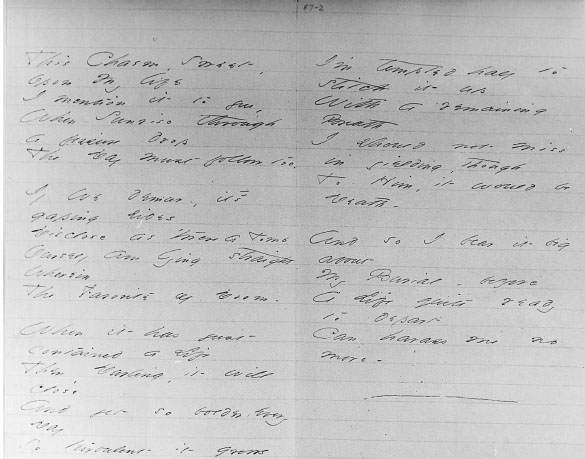

Consider some lines that seem to enfold within themselves the central writerly strategies of feminized lyric sentimentalism at the same time that they address the readerly anxieties in which those strategies were located. The lines appear to have been written around 1865, exist in manuscript (

fig. 35

) only in one of the unbound sets (6b), were first published in 1945, and are now known as Poem 1061 in the Franklin edition:

This Chasm, Sweet, upon my life

I mention it to you,

When Sunrise through a fissure drop

The Day must follow too.

If we demur, it's gaping sides

Disclose as âtwere a Tomb

Ourself am lying straight wherein

The Favorite of Doomâ

When it has just contained a Life

Then, Darling, it will close

And yet so bolder every Day

So turbulent it grows

I'm tempted half to stitch it up

With a remaining Breath

I should not miss in yielding, though

To Him, it would be Deathâ

And so I bear it big about

My Burialâbefore

A Life quite ready to depart

Can harass me no moreâ

The close relation between these lines and the lines that begin “On the World you colored” is immediately apparent: both texts are directly addressed, both make the figure of address complicit in a past scene of suffering now intimately associated with the scene of writing, and both collapse the misery of one into the misery of the other. Yet while in “On the World you colored” the deictic “wrinkled Finger” that implicitly points to a referent that the subject cannot explicitly articulate concludes the poem, the lines above begin in such a moment of pure deixis, of sheer pointing. And whereas “On the World you colored” projects the consubstantial fusion of past and present, self and other, suffering and its representation onto the landscape, “This Chasm” proceeds from its “mention” of painful experience to the progress of its internalization, its

incorporation

by a subject who, like a sentimental lyric, can disclose her meaning only by performing itâthat is, by being read. The textual subjection of this subject is, then, by the last line, both a testimony to the authenticity of her pain and an acknowledgment that lyric testimony will inevitably be read as only the figurative performance (rather than the historical experience) of that referent. The self-become-tomb-become-poem finally introjects an entire literature of miseryâand an entire legacy of readingâinto itself.

Figure 35. Emily Dickinson, around 1865. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 87-1, 87-2).

The sort of sentimental reading that such a subject invites may explain why most twentieth-century critics steered clear of these lines. When Gilbert and Gubar considered “This Chasm” briefly in their consideration of Dickinson's work as “versified autobiography,” they registered their discomfort with its invitation by deciding that the poem “parodies the saccharine love poetry that ladies were expected to write.”

28

Yet these lines do not feel like a parody; the ironic distance we usually associate with that mode is wholly absent from their headlong plunge into pathos. Rather, the lines' immediate emphasis on the nondiscursive basis of their own discourseâon a “This” that could be demonstrated without linguistic illustration to a “you” intimate enough to see itâengages in savagely foreshortened perspective the contradiction inherent in the nineteenth-century

reception

of lyric testimony. When Gilbert and Gubar asked, “What specifically is the chasm this poem describes?” they neatly marked the semantic territory that separates Dickinson from her modern audience. No nineteenth-century reader would have needed to pose that question; the first line's referential conceit (rather like Hamilton's “agony of self-abasement”) would have been too obvious not to be seen, and its visibility poses the question of parody at another level. The materials the lines work upon are not simply the materials of conventional sentiment, but the discourse positioning that sentiment in relation to the reader: from its first word, the lines dare a reader like Griswold or Bowles or Higginson to detach this subject's pain from her aesthetic claimsâand end by daring him not to do so.

For certainly here there is everything to be endured and nothing to be done. Nothing, that is, but to “mention” what Arnold surely would have called a “class of situation from the representation of which, though accurate, no poetical enjoyment can be derived.” So the first lines apologize by

understating the effect of their own opening: a “Chasm” is hardly something one

mentions,

especially not after having pointed directly to what Bowles would have called the writer's “lacerated bosom.” Not healed and therefore not prepared to “gladden other natures with the overflowings of a healthful life,” the life the chasm interrupts cannot, apparently, help but attest to its interruption; Bowles counseled the new day's power to heal old wounds, but this “Sunrise” has already reversed such a progressive temporality. The disappearance of day “through a fissure” turns the naturalizing logic of Bowles's view against itself, and the poetic logic that “must follow” upon natural reversal must naturally be reversed. In four lines Dickinson turns inside-out not the perspective of the literature of miseryâshe adheres to that with a vengeanceâbut the perspective on the poetry of feminine suffering that would seek to wedge itself between a life and its “proper” representation.

Now the division of the proper, of the self from itself is, as we have seen, perhaps the signature characteristic of the subjectivity Dickinson bequeaths to literary historyâit has, in fact, often been understood as the sign of Dickinson's modernity. Any reader of Dickinson can generate a long list of chasms, fissures, maelstroms, cleavings, self-burials, and horrors that irrevocably divide one part of the “I” from another. Nearly all of the commentary devoted to Dickinson has centered on the question of these self-splittings, and especially on the referent of this schizophrenic subjective representation: sheer grief, lost love, physical and psychic pain, gendered, artistic, and sexual misinterpretation and oppression have all vied as explanations for the missing referent of the crisis. Yet what is not often considered is that whatever the answer might turn out to have been to the riddle of subjective experience the lyrics present, that riddle is most often portrayed as a problem for lyric

reading.

29

We might go so far as to say that the anticipation of that reading is exactly what fractures the subject: she experiences at the level of her person the fate of her representation, and it is a fate consistently figured as a crisis of or for bodily identity, as in these lines from the same set (6b) in which the lines that begin “This Chasm, Sweet ⦔ were copied:

I've dropped my BrainâMy Soul is numbâ

The Veins that used to run

Stop palsiedâ'tis Paralysis

Done perfecter in stoneâ

Vitality is carved and coolâ

My nerve in marble liesâ

A Breathing Woman

Yesterdayâendowed with Paradise.

Not dumbâI had a sort that movedâ

A Sense that smote and stirredâ

Instincts for Danceâa caper partâ

An Aptitude for Birdâ

Who wrought Carrara in me

And chiselled all my tune

Were it a witchcraftâwere it Deathâ

I've still a chance to strain

To Being, somewhereâMotionâBreathâ

Though Centuries beyond,

And every limit a Decadeâ

I'll shiver, satisfied.

(F 1088)