Dickinson's Misery (39 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

Here, as in “This Chasm, Sweet â¦,” an unnatural occurrence inevitably or “naturally” eventuates in the subject's metamorphosisâher transubstantiationâinto “dumb” matter, the artifactual object of her own regard. The comic corporeality of the first line challenges the reader to imagine a “Brain” rather than, say, a

mind

registering the shock of transformation or “Paralysis” from “Breathing Woman” to memento mori. Further, the third stanza identifies the talents of the formerly embodied self as those of the poet, or of performative lyric agency: “Not dumbâI had a sort that movedâ / A Sense that smote and stirredâ / Instincts for Danceâa caper partâ / An Aptitude for Birdâ.” The fourth stanza then asks the question the reader might be expected to ask, the one readers of Dickinson always do ask:

What happened? Who or what effected the change?

And, as so often in Dickinson's lines, the answer is deferred toward a future readerly resurrection in which the “I” may “strain // To Being, somewhere â¦,” though “MotionâBreath” may “Centuries beyond” merely “shiver” beneath the text's rigidified, now differently embodied surface. When Dickinson first wrote to Higginson, she began, we recall, with what must have seemed to her future editor a “half-cracked” question: “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” (L 260); upon his immediate reply as to whether he thought “it breathed,” she then thanked him “for the surgery,” explaining “I could not weigh myselfâMyself” (L 261). Already, in this inaugural literary correspondence, the dissecting hand of the critic has intervened between “myself” and “Myself.” The question Dickinson posed to Higginson remains the one her readers keep never answering: can the reception of a lyric weigh the subject within the artifact? Where might “Motion” and “Breath” remain after they have been removed from “a sort that moved”?

The pathos of that question may gain a certain resonance, I have argued, in the post-Higginsonian (that is, post-nineteenth-century) history of the reception of Dickinson's progressively idealized and abstracted lyric voice, but it has another reverberation within the discourse of nineteenth-century sentimental lyric. In one popular poem on the subject of such poetry, for example, the type of lyric agency that Dickinson condensed into “An Aptitude for Bird” took the familiar form of the nightingale's song. “The Poet,” by the well-known writer Elizabeth Oakes Smith (whose poetic character of Eva in her long narrative verse “The Sinless Child” [1842] probably informed Longfellow's best-selling “Evangeline” in 1847 as well as Stowe's enormously influential “little Eva” in 1851) opens with two epigraphs: “It is the belief of the vulgar that when the nightingale sings, she leans her breast upon a thorn,” and then “

NON VOX SED VOTUM

” (not a voice but a vow). The poem as a whole goes on to elaborate the relationship between the two halves of both epigraphs: between incorporeal voice and the body's silent “vow,” between misery and its utterance, poetic voice and the testimony of pain, a received literary identity and the antithetical experience it lifts into metaphor:

Sing, singâPoet, sing!

With the thorn beneath thy breast,

Robbing thee of all thy rest;

Hidden thorn forever thine,

Therefore dost thou sit and twine

Lays of sorrowingâ

Lays that wake a mighty gladness,

Spite of all their mournful sadness.

Sing, singâPoet, sing!

It doth ease thee of thy sorrowâ

“Darkling” singing till the morrow;

Never weary of thy trust,

Hoping, loving as thou must,

Let thy music ring;

Noble cheer it doth impart,

Strength of will and strength of heart.

Sing, singâPoet sing!

Thou art made a human voice;

Wherefore shouldst thou not rejoice

That the tears of thy mute brother

Bearing pangs he may not smother,

Through thee are flowingâ

For his dim, unuttered grief

Through thy song hath found relief?

Sing, singâPoet, sing!

Join the music of the stars,

Wheeling on their sounding cars;

Each responsive in its place

To the choral hymn of spaceâ

Lift, oh lift thy wingâ

And the thorn beneath thy breast

Though it pierce, shall give thee rest.

30

According to convention, Oakes Smith's apostrophic refrain urges the nightingale-Poet to turn her suffering into songâand in each stanza the rationale for doing so is the vicarious pleasure her “Lays of sorrowing” may bring. If we recall once again Shelley's definition of the poet as “a nightingale, who sits in darkness and sings to cheer its own solitude with sweet sounds,” we might also recall that “his auditors are as men entranced by the melody of an unseen musician, who feel that they are moved and softened, yet know not whence or why.” Oakes Smith emphasizes the source (the “whence or why”) of this romantic affect and, in her echo of Keats's signature adjectival adverb from stanza six of the Nightingale Ode (“Darkling I listen ⦔), she also emphasizes that the affective transference characteristic of romantic poetics has its feminized or “vulgar” origin. “The Thorn beneath thy breast” is the source of the nightingale's song, but it is not her pain that she expresses; the “hidden thorn” is instead progressively removed through each stanza from the “mighty gladness,” the “noble cheer,” the “relief” it gives to “thy mute brother,” and ultimately joins “the choral hymn of space” in an elevated constellation that transcends the pathetic corporeality of the bird's “lacerated bosom.”

Yet while that figural progression constitutes the logic of the ode's counsel to the nightingale, it does not account for the logic of the poem itself: this is not the lyric the nightingale sings; its theme is instead the “vow” of the martyred body that enables the imaginary version of lyric song that the nightingale

would

produce. It is a view, as it were, behind the wings of poetic production. As Oakes Smith wrote in 1851 in her feminist treatise

Woman and Her Needs,

pain is the proper subject for women's poetry because it has been used to define women

as

subjects: “suffering to a woman occupies the place of labor to a man.”

31

If suffering was taken to constitute women's “natural” or proper literary identity, in other words, Oakes Smith suggested that women turn that inheritance into capital.

32

When Dickinson begins the lines “This Chasm, Sweet” by pointing deictically to a wound that both motivates the poem and for which the subject

of the poem herself is the only evidence, she participates in what Foucault would call a nineteenth-century lyric episteme in which the body is called upon to validate the representational claims made in its name, but from which that very representation severs it.

33

Like Oakes Smith's “The Poet,” Dickinson's lines insist on the invisible “vow” or promise that guarantees the sympathetic power of voiceâbut in “This Chasm” it is the mute body and not the voice that defines the subject. In effect, each quatrain works to close the gap between medium and message opened by “the belief of the vulgar” that Oakes Smith's poem exemplified, and they do so, as in “I've dropped my Brain,” by identifying the “Vitality” of the subject with an uncanny “Life” and afterlife of the lyric text. Yet “identifying” does not feel like the right verb for what emerges as a competition between this “I” and the “Chasm” which, in the second and third stanzas, threatens to contain “a Life” in much the same way that “A Breathing Woman” is contained by her “chiselled” figuration in “I've dropped my Brain.” The second stanza casts the threat in the idiom of carpe diem lyric, and specifically of Marvell's “To His Coy Mistress,” in which the poet consigns the demur object of his desire to a “marble Vault” if she refuses his advances.

34

The reversal of the sun's logic thus allows for more than one kind of lyric reversal in Dickinson's lines, and the appealingly sinister humor with which “Ourself” becomes “The Favorite of Doom” is reminiscent of the parodic subjective confusion occasioned by Hamilton's reiteration of her “true” or “natural” literary identity. Marvell's “fine and private place” has become the open secret disclosed in Dickinson's lines: the consequences of her desire now seem to make her the property of an agency bent on her subjection.

On a rhetorical level, what has happened between the first and second stanzas is that the pure deixis of the poem's opening “This” has turned into metaphor in the sixth line's “as âtwere.” Once given a name, the metaphor takes over, shifting from the metonymic “upon” of the first line to a near-substitution for the “I” that almost becomes the metaphor's tenor. Almost. Just at the moment when, in the third stanza, the “bolder” and “turbulent” intention of the vehicle closes upon its living captive, another intention asserts itself. The temptation “to stitch it up” rather than be fastened by the figure of the Tomb promises some releaseâif not of the self, then of an “I” grammatically distinct from “Him,” no longer vicariously identified as an “Ourself.” The “MotionâBreathâ” temporally deferred and syntactically excluded in “I've dropped my Brain” becomes the envelope of “This Chasm,” and the “I” nearly subjugated by lyric desire instead ends by enclosing it. This “stitch” of “Breath” rather exactly poises her text between the body and its material impression. The conceit of pregnancy in the final stanza resurrects the feminized, unrepresentable

because overrepresented body of the woman writing in the perverse terms of “genuineness” Griswold prescribed for “female poets”: the “power to originate [or] even, in any proper sense, to reproduce” may not, after all, define Dickinson's “genius.” What may come closest to defining it is the way in which “a Life” remains in her writing in excess of the figures of that writing, the way in which her practice contained without becoming the lyric stuff of which she made it and out of which it was to be made.

ND BORE HER SAFE AWAY

”

Dickinson did and did not do what the poetesses in the print public sphere did so well: she did hypostatize the figure of the generic, suffering woman, but she did not abstract that figure into a personification that became the property of that sphereâor at least it did not become such an abstraction until well after the era of sentimental identification had passed.

35

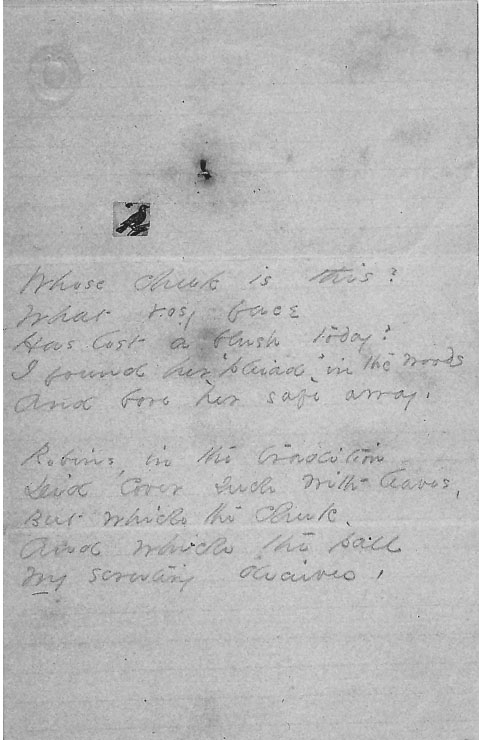

Instead, she folded that public personification, as she folded other poetic genres, into texts that often point away from rather than toward their subject. A page she sent to Susan in early 1859, for example (

fig. 36

; H B186), carries some lines that, printed as a lyric for the first time in the twentieth century (by Martha Dickinson Bianchi in

Emily Dickinson Face to Face

in 1932), are not very interesting:

Whose cheek is this?

What rosy face

Has lost a blush today?

I found herââpleiad'âin the woods

And bore her safe awayâ

Robins, in the tradition

Did cover such with leaves,

But which the cheekâ

And which the pall

My scrutiny deceivesâ

(F 48)

Although the flower to which “this” pointed is no longer on the page for the word to point

to,

on the manuscript its imprint is still visible. Visible as well is the small paper bird that Dickinson cut from

The New England Primer.

36

In the

Primer,

the bird is a nightingale, and it (along with another nightingale, from which Dickinson's cutting isolated it) illustrates the letter

N

accompanied by the dimeter couplet, “Nightingales sing / In time of Spring.” Susan would have known that the nightingale, tiny as it is,

was

a nightingale, because it was one of the images that taught her (and everyone else in the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) to read. As we noticed in the third chapter in the valentine to Cowper Dickinson that consisted of cut-outs from the

Primer

and adapted lines from an old ballad, “while seeming to bind the alphabet to orthodoxy,” as Patricia Crain writes, the

Primer

“in fact bound it firmly to everyday life.”

37

In attaching the image of primary, everyday literacy to her lines, Dickinson also framed those lines

as

primary, everyday literacy of and in a particular genre. The frame of that genre is just being made visible in print by the new critics of women's sentimental lyric, but the frame of Dickinson's framing of that genre is invisible in print, though it is itself the creature of print. Dickinson's invocation of the figure of birdsong as the figure of the lyric has become a familiar strain in these pages, and her late nineteenth-century readers' reception of her verse as birdsong attested to the persistence of the trope that would be replaced by the trope of the lyric “speaker” in the twentieth century. The identification of poetesses

with

the nightingale as an image for the figure of the Poetess was about as common as the identification of letters in the

Primer:

Oakes Smith's “The Poet” was an exemplary instance of the countless wounded birds individual poetesses provided to illustrate the alphabet of sentimental lyric literacy.

Figure 36. Emily Dickinson to Susan Gilbert Dickinson, 1859. The string that held the flower and the flower's stain are still visible to the right above the nightingale. By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.