Dickinson's Misery (41 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

Or ratherâto shift from an expression of personal preference to a proposal about historyâI do not believe that

modernism

can ever escape from such an equation. By “lyric” I mean the illusion in an artwork of a singular voice or viewpoint, uninterrupted, absolute, laying claim to a world of its own. I mean those metaphors of agency, mastery, and self-centeredness that enforce our acceptance of the work as the expression of a single subject. This impulse is ineradicable, alas, however hard one strand of modernism may have worked, time after time, to undo or make fun of it. Lyric cannot be expunged by modernism, only repressed.

Which is not to say that I have no sympathy with the wish to do the expunging. For lyric in our time is deeply ludicrous.

1

Why so idealize and so renounce the lyric? I have been suggesting that the lyric has come to seem so ideal and so ludicrous because it has been progressively identified with a form of personal abstraction that cannot quite be disowned, and yet cannot quite be embraced by modern critical culture. That is why Dickinson is such a perfect and pathetic figure for it, though that is the last thing she may have wanted to be.

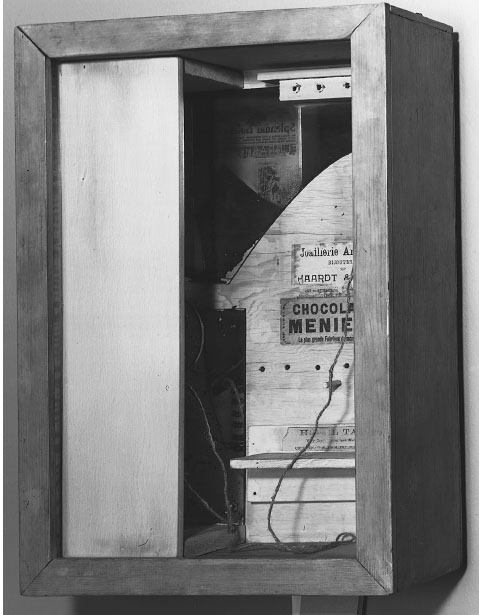

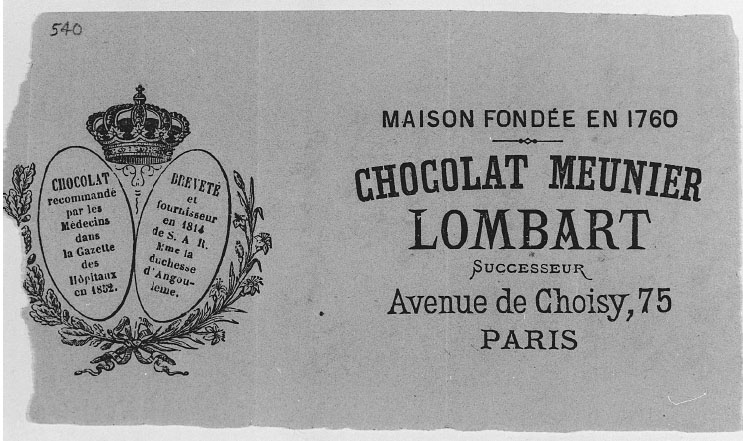

In the 1950s, Joseph Cornell made a series of collage boxes inspired by things he had read by and about Emily Dickinson, and especially by her habit of using domestic scraps and objects as surfaces and enclosures. The most famous of those boxes, “Toward the Blue Peninsula” (1953), represents a pristine cage of isolation, a white box, the traces of a birdcage, white mesh wire, a blue window of lyric possibility. A less often seen box, “Chocolat Menier” (1952) (

fig. 37

), is much more cluttered, since it represents some of the things the absent subject has left behind: a chocolate wrapper, bits of string, a hidden shard of mirror pasted opposite a hidden, suspended metal ring in the cage from which the bird has flown. The chocolate wrapper (

figs. 38a

,

38b

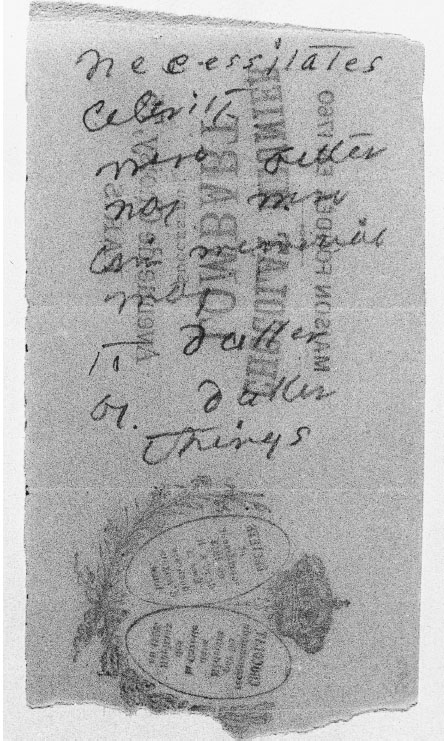

) on which Dickinson wrote some lines that have never been published as a poem was reported to Cornell by Jay Leyda, who catalogued it for the archive in Amherst; Cornell never read the lines themselves or saw the thin yellow wrapper in the archive, and he did not reproduce the lines on the back of the package of this expensive imported item newly available in New England in the 1870s (and made by the first industrial chocolate manufacturer and exporter in France). The lines or words or note or fragment,

Figure 37. Joseph Cornell,

Chocolat Menier.

1952, mixed media construction (17 1/4 Ã 12 Ã 5 inches). Grey Art Gallery, New York University Art Collection, Anonymous gift, 1966. Courtesy of the NYU Art Colletion.

Figure 38a. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 540).

Figure 38b. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 540).

necessitates

celerity

were better

nay were

im memorial

may

to duller

by duller

things

are inscrutable, since everything that would explain them is missing.

2

What is missing is in turn what lyricizes the notion of the unread lines, or the private circumstances of an imaginary inscription on mass-produced print. Cornell frames what cannot be published, and in doing so turns toward its public the twentieth-century abstraction of the lyric, an idea of expression more telling than the poem that was never there.

B

EFOREHAND

1

. In a letter to Mrs. C. S. Mack in 1891, Dickinson's sister Lavinia wrote, “I found (a week after her death) a box (locked) containing seven hundred wonderful poems, carefully copied” (17 February 1891; cited by Thomas H. Johnson in his introduction to

The Poems

[J xxxix]). This citation is one source for my narrative, though the tone and several of the details are drawn from Millicent Todd Bingham's sensationally partisan account of the “discovery” and publication of the poems in

Ancestors' Brocades.

Evidently, Dickinson's sister did burn many of her extant papers though there is nothing in the will directing her to do so. That Lavinia thought that the destiny of the poems was to appear “in Print,” as she put it, is clear from her many letters to the poems' first editors, Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson, and to the publisher, Thomas Niles of Roberts Brothers. Since these letters, the journals of Loomis Todd (in the Yale University Library) and the notes of Higginson (in the Boston Public Library) offer various versions of the manuscripts' recovery, my narrative is intentionally selective. A lucid narrative of the manuscripts' recovery and edition is offered by R. W. Franklin in his introduction to his edition of

The Poems of Emily Dickinson.

Susan Dickinson, the recipient of the greatest number of Dickinson's addressed manuscripts, did not write her own version of the story of the manuscripts' recovery, but her daughter, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, gives another wonderfully partisan account of that family's matrilineal transmission of the manuscripts in the introduction to

The Single Hound.

For that family's history of manuscript transmission, see Martha Nell Smith's and Ellen Louise Hart's introduction to

Open Me Carefully

. My account is a pastiche of these sources, and it is liberally influenced by my own experience of “discovering” the diversity of Dickinson's less carefully copied manuscripts (which may or may not have been in the locked box).

2

. J. V. Cunningham, “Sorting Out: The Case of Emily Dickinson,” in

The Collected Essays,

354.

3

. Norman Bryson,

Looking at the Overlooked,

140.

4

. See Robert Weisbuch,

Emily Dickinson's Poetry,

19; Jay Leyda,

The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson,

1:xxi; Geoffrey Hartman,

Criticism in the Wilderness,

129.

5

. For the 1980 reading, see Margaret Homans,

Women Writers and Poetic Identity,

194. Homans goes on to critique the strictly metaphorical interpretation that results when the lines are printed out of context, but she reads the lines lyrically nonetheless, and builds an argument about the relation between prose and poetry based on them: “Because the rhyming lines seem to grow spontaneously out of prose, they appear (whether or not Dickinson contrived the effect) to represent the untutored origins of poetry, as if poetry originated in imitation of nature” (195).

6

. Mabel Loomis Todd, ed.,

Letters of Emily Dickinson

; Martha Dickinson Bianchi, ed.,

The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson

; Mabel Loomis Todd, ed.,

Letters of Emily Dickinson

; Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Ward, eds.,

The Letters of Emily Dickinson

.

7

. See Charles Taylor,

Modern Social Imaginaries

, for the abstraction of the social imaginary. According to Taylor, “the social imaginary is not a set of ideas; rather it is what enables, through making sense of, the practices of a society” (2). Taylor follows Cornelius Castoriadis, who uses the term to refer to “the final articulations the society in question has imposed on the world, on itself, and on its needs, the organizing patterns that are the conditions for the representability of everything that the society can give to itself” (

The Imaginary Institution of Society,

143). He also follows (as do I) the work of Benedict Anderson in

Imagined Communities

. On this logic, the lyric would be one such organizing pattern that takes distinctive shape in nineteenth-century print culture and shapes the growth of American literary criticism in the twentieth century.

8

. Alistair Fowler puts the observation most succinctly when he warns that “lyric” in literary theory from Cicero through Dryden is “not to be confused with the modern term” (

Kinds of Literature,

220). We will return in the next two chapters to the lyricization of postromantic poetryâand especially to the lyricization of Dickinson's writing as modern poetry. The phenomenon is aptly characterized by Glenn Most in an essay on ancient Greek lyricists:

Some of us ⦠may wonder what other kind of poetry there is besides the lyric. For a number of reasons it has become possible in modern times to identify poetry itself, in its truest or most essential form, with the lyricâ¦. This is not to say that satires or poems for affairs of state have altogether ceased to be written; but these tend to be relegated to a secondary rank, whereas the essence of poetry is often located instead in a lyric impulse.

See Most, “Greek Lyric Poets,” 76. As we shall see, the “number of reasons” to which Most alludes remain to be historically enumerated more carefully. The problem, of course, is how to do that. W. R. Johnson solved the problem in

The Idea of the Lyric

: by claiming that the lyric is transhistorical, a transcendent idea. M. H. Abrams made a start for a more historical approach to the nineteenth century in his “The Lyric as Poetic Norm” in

The Mirror and the Lamp,

84â88, but surprisingly few scholars have extended his scant comments there. As we shall see, among those who have done so are Douglas Patey, whose “âAesthetics' and the Rise of Lyric in the Eighteenth Century” is invaluable for its history of the lyric's ascendancy to “truest or most essential form”; Seth Lerer, “The Genre of the Grave and the Origins of the Middle English Lyric”; Mark Jeffreys, whose “Songs and Inscriptions: Brevity and the Idea of Lyric” makes a start for the difference between Renaissance genres and modern lyic ideas; and Stuart Curran,

Poetic Form and British Romanticism.

9

. Susan Stewart, “Notes on Distressed Genres,” in

Crimes of Writing,

p. 67. It should be said that not only does Stewart not include the lyric as a “distressed genre,” but she considers distressed genres opposed to avant-garde genres, since “the avant garde is characterized by a struggle against generic constraints” while “the distressed genre is characterized by a struggle against history” (92). Thus implicitly for Stewart the distressed genre would be reactionary and the avant-garde resistance to genre progressive. In

chapter 2

, we will return to Stewart's characterization

of the lyric as both antigeneric (or avant-garde) and antihistorical (or distressed).

10

. Gerard Genette,

The Architext,

2. Genette's rereading of what he eloquently describes as the

lectio facilior

of finding the lyric where it was not in Plato and Aristotle should revise many accounts of modern poetics. Especially suggestive is Genette's conclusion that “modes and themes, intersecting, jointly include and determine genres” (73).

11

. Mark Jeffreys, “Ideologies of Lyric: A Problem of Genre in Contemporary Anglophone Poetics,” 200. Jeffreys's essay is particularly valuable for its exposition of the ways in which “the recent struggle to clear away New Critical poetics and to make room for a postmodernist poetics” (203) has often made the mistake of aligning the lyric itself (whatever that is, and Jeffreys is quite aware that generic definition is the question) with a reactionary critical ideology. For an earlier suggestive discussion of the problems entailed by the modern critical elevation of the lyric (and especially the critical abstraction of the romantic lyric), see Marjorie Perloff,

Poetic License.