Diamond in the Rough (9 page)

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

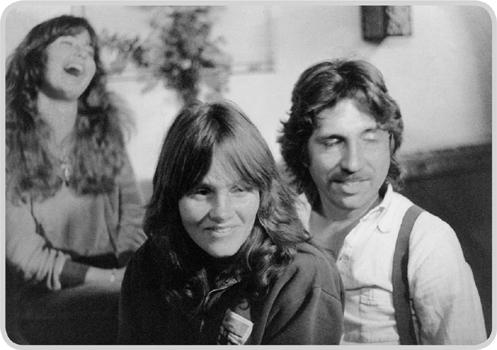

At a bar with Mom and Dad, 1978

(Photograph courtesy of Marti Cruthers)

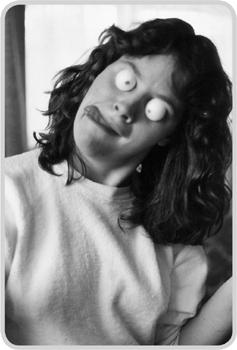

I gained sixty pounds in three months and looked like a whale. I was twenty-two and fat and drunk and living with my parents, a far cry from the girl who just a few years back had seemed so full of promise. To top it all off, I got a job taking care of rats in the university vivarium—the place where they kept animals for experimentation. I needed money to get myself out of town to go somewhere, anywhere. I would wake up in the morning and put on the only things that fit—a pair of ratty sweatpants and my dad’s T-shirt, and head out to clean up rodent shit. It was a low point, to be sure. But something was coming alive in me, because I would sneak off from rat duty and write little tidbits of lyrics. These weren’t the musings of a teenager attempting to imitate a hero. I had grown up a bit and had something to say about it.

No one ever said it was easy.

I’ve always been along for the ride,

Thinking there would always be

Someone to take the wheel for me,

But I was helpless sitting passenger side …

Not exactly brilliant, but it was

me

speaking, reflecting, trying to get at something. It was new. But it would be many years before I started to believe I could really write.

Like I said, fat and drunk, 1979

I am weaving like a drunkard, like a balloon up in the air.

I am needing a puncture and someone to point me somewhere.

Having cleaned up enough rat shit to last a lifetime, I finally had enough money saved to try leaving home again. This was the real thing, do or die. My old boyfriend, Jim Bruno, had moved to Berkeley and loved it. Armed with my guitar, my protective layer of fat, and a daily ration of alcohol, I headed out for the San Francisco Bay area in the spring of 1979.

I moved into a large, rambling, run-down house in Berkeley with Jimmy and a few other misfits, in an attic room with a skylight. Many were the nights that I drank a six-pack of Coors and crawled out onto the roof from where I could see out across the bay to the lights of San Francisco. I remember precious little about my yearlong stint in the Bay Area, because I was drunk most of the time. I call it my lost weekend.

Most of my roommates were Deadheads. They didn’t drink Coors; they ate watermelon laced with acid. Let me say right now, with all apologies, that I never dialed in the Grateful Dead. You either get it or you don’t, and I am not among the converted. To me my roommates were what I imagined vintage San Franciscans to be, all Haight-Ashbury and free love and you better wear some flowers in your hair. One morning I was in the kitchen and one of my roommates, Julie, a lanky, wire-rimmed, long-stringy-haired, peasant-skirted, pit-hair-baring, sandal-wearing gal, stumbled in. As I was pouring myself a glass of orange juice, she said, “Hey, man, can I have a hit of your smoothie?”—assuming, naturally, that it was spiked with something.

The first order of business was getting a job, naturally, but that took some time, and in the interim I developed a ritual. After recovering from my morning hangover, I would scan the classifieds and make feeble attempts toward employment. Then something divine happened.

The documentary about the Who,

The Kids Are Alright,

came to the local cinema. I went to see it one afternoon and fell head over heels in love with the band. My musical leanings had veered from a well-balanced overview, and due to my unbending allegiance to the Beatles I ignored what I thought to be lesser bands like the Stones, the Kinks, Led Zeppelin, and the Who, among others. I went again the next day. And the next, and the next. Some days I just sat in the theater waiting for the next show and saw it twice. I have no idea how many times I saw that movie but it was

a lot.

At night when I was going to sleep, I fantasized about meeting them, just as I’d done with the Fab Four when I was nine. I was twenty-three! Never mind. I was in love. Yes, of course I’d seen Woodstock, but I’d passed over them in favor of Crosby, Stills & Nash and Joan Baez. Now I finally got it. Only four guys and three instruments. One guitar player—and what a guitar player. Pete, Pete, Pete. There he was in his white jumpsuit, lovingly bent over his ax with bloody fingers, or windmilling and leaping for all he was worth, like a punk ballerina. Oh, I wanted to be him. Let’s not even mention his songwriting. The mind boggles. And of course Roger, god of six-pack abs and mike-whirling finesse; the stoic, solid John Entwistle on bass; and the one-in-a-million carnival ride of a drummer, Keith Moon. But finally the sad day came when I got a job, and my secret afternoons with

The Kids Are Alright

had to end.

I was hired by a stained-glass store in Oakland as a salesperson. I learned how to cut and handle glass, but not without a few minor accidents that put me closer to emulating dear Pete at his bloody best. I made fast friends with a woman named Shelley Arrowwood. She was amused by the way I put down our insane boss and decided that

this

kid was all right.

Shelley had taken on her last name when she grew tired of changing it every time she got married, which was fairly often, so she legally became “Arrowwood,” nature lover to the core, for good and always. I called her “Arrowhead,” and she called me “Shufflefoot McQueen”—I’m not sure why, although I think it had something to do with the fact that I shuffled like a downtrodden subordinate every time our drill-sergeant boss commanded me to make coffee, muttering under my breath as I inched toward the coffeemaker.

We had a quick, easy, shorthand of a friendship, and I spent lots of time with her and her then-spouse, Richard. Shelley was a football-loving, hard-drinking, foul-mouthed little thing, and Richard was a refined and professorial die-hard feminist. One night as we were watching TV, an ad came on for what was then a revolutionary development in sanitary napkins—the three adhesive strips. Richard took this in and suddenly erupted in outrage. “Jesus! Look at what they put you through! This is unbelievable!” Shelley and I stared at him blankly for a minute until we finally understood—Richard, in his hypervigilance to root out the atrocities done to women, was under the impression that one took the sticky part of the pad and applied it directly to the crotch. Ouch.

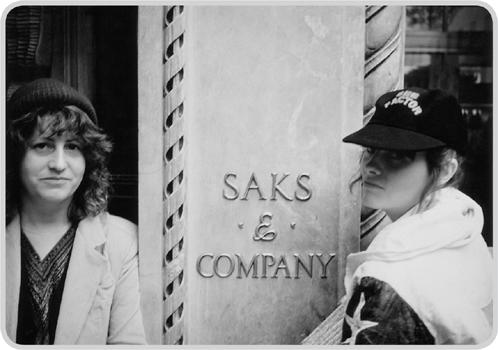

Shelley

Musically I was keeping things strictly acoustic—no more bands for me—and found a home at Laval’s Subterranean in Berkeley, yet another basement bar. Jim was still writing songs, and I was finally getting a clue that doing original music might be a good idea. I did a lot of his tunes, plus material by Tom Waits, Bruce Springsteen, and Bob Dylan. Covering songs by men was a good trick I had discovered—sometimes the simple fact that a woman was singing the song would give it another dimension. It was during this period that I taught myself to play “The Heart of Saturday Night” by Waits and “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go” by Dylan. For the first time, I felt that there was something special going on with my interpretations, and ultimately both those songs made it onto my third record,

Cover Girl.

Me and Jim Bruno, Berkeley, 1979

(Photograph courtesy of John Palme)

Although I still didn’t write my own songs, it’s worth noting that I was always fooling around on the guitar, and from time to time I would compose little ideas here and there:

I’ve been sleeping fair,

Lately I could swear I’m thinking

Clearer and clearer,

And I’ve been working hard,

Looking at my punch card and

My mirror, my mirror …

I went back to this tidbit years later and finished it, called it “Ricochet in Time,” and included it on my first record,

Steady On.

It’s a song I still love to perform, because it describes being a musician on the road. In fact, it means a lot more to me now than it did when I wrote it.

I don’t know how long I might have stayed in the Bay Area, but a year after I moved there, fate intervened when I got a phone call that set the wheels in motion to significantly change the rest of my life, both personally and professionally. The Big Apple beckoned.

The Buddy Miller Band—Karl Himmel, Buddy, me,

Larry Campbell, and Lincoln Schleifer—NYC, 1980

You’re shining, I can see you.

You’re smiling. That’s enough.

I’m holding on to you

Like a diamond in the rough.

New York City, just like I pictured it. I had visited there exactly once, and it had made me dizzy with its immensity. I would never have possessed the nerve to move to Manhattan without a single connection, but Buddy Miller tracked me down in California and asked if I would join his band. I knew Buddy from my days in Austin, and he’d gone up to New York to hop onto the bandwagon of what became known as the great country scare of the 1980s, what with urban cowboys, Gilley’s, electric-bull riding, and two-stepping. All the things I’d already seen and heard in Austin were now trendy in New York, and Bud went there to see what could be done about enlightening the Yankees to a bit of homegrown, honestly-come-by, grassroots, serious-assed country music. Never mind that Buddy was a Jew from New Jersey. God didn’t get the right memo about Bud.

I was to replace Julie Griffin, one of the deepest, purest singers and songwriters ever. She was Buddy’s girlfriend at the time (and is now his wife) but had had enough of bars and bands and brawls and vans and boys and smoke and sawdust and beer, and she went back home to Texas. I accepted the job and moved to New York in November of 1980.

Buddy must have been really bereft when Julie left the band. After all, he left to join her less than a year later. He never showed it, though. Our band was close, but we didn’t confide in each other. Our private lives were private, or as private as they could be while we were living out of a van together. I knew that Bud liked Chinese-Cuban food and had the most extensive record collection of any of us. I knew he could sing and play the guitar like a maniac, there being a complete disconnect between this gentle soul and this ferocious player.