Diamond in the Rough (7 page)

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

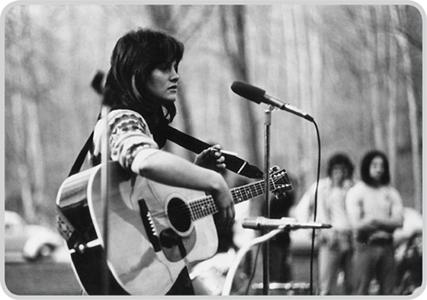

Eighteen years old, 1974

(Photograph courtesy of Jim Bruno)

I wasn’t born, I got spat out on a wall,

And nobody knew my name.

The sun hatched me out, cradle and all,

On the corner of First and Insane.

I couldn’t wait to get out of The House. I took summer school for two summers straight in order to graduate from CCHS a year earlier than my friends, to graduate in Rollie’s class. We had a fantasy of living on a remote shore in Australia after he got a degree in marine biology, and attending SIU together was a good start. In 1973, at the age of seventeen, I packed myself up and flew the coop with Rollie to the Thompson Point dorms, which were all of maybe three miles from Norwood Drive.

It was kind of a case of the emperor’s new clothes. I was hell-bent for leather on becoming independent, but I really didn’t have a clue about what to do next. The only reason I attended college at all was spite—I’d been told so many times by my high-school teachers how hard college would be that I had to prove a point, I suppose. I took refuge in required freshman courses like earth science and algebra, and as far as I could tell, they weren’t any different from high-school classes except that they were way bigger and the teachers gave less of a damn.

One of my electives was modern dance. Don’t ask me why, because I’m one of the least graceful people on the planet, and our first assignment was to make up a solo piece about something we did in our everyday lives. I painfully recall trying to “be” a shower; let’s just leave it at that. Truly, I was a buffoon with regard to the whole undertaking of SIU, now that I had a choice in the matter. I had absolutely zero interest in studying anything that I can now, in hindsight, imagine I might have enjoyed. Music theory, no thanks. Philosophy, poetry, religion, art history, even the drama department didn’t feel right, and here’s the reason: My sense of balance was built on pretty thin ice, and without the confines of home, which afforded me something to rebel against, I was lost and extremely insecure. I’d never thought realistically about my vocation—it seemed to me that the world of academia, so revered by my family (my father had his Ph.D. by then, and Geoff was at Harvard on scholarship), was a drag, and I just always figured I’d do something “fun” like acting or painting or singing. Well, I was a mediocre actress and an even worse artist.

However. I could sing. And where does one go to sing in a college town that likes to party? Right down to Illinois Avenue, the “strip,” to any dive that would hire me. My first official paying gig was at a bar called the American Tap, an old house converted into a bar. Colonial decor. For thirty dollars I played four forty-five-minute sets consisting of songs by Joni Mitchell, Paul Simon, James Taylor, Carole King, Bonnie Raitt, Judy Collins, CSN&Y, Jackson Browne, Judee Sill, and, of course, the Beatles. I loved it. I felt like I was doing what I was meant to do. I entered my sophomore year at SIU but rarely attended class. Too embarrassed to drop out formally, I just let it go.

Either I was playing somewhere or I was sitting in with someone else who was, more often than not, getting drunk in the process. I let Rollie go, too, and started dating a local musician named Jimmy Bruno. We lived the nightlife, closing down the bars and heading to whatever party ensued after that. Then we’d end up at Denny’s for a predawn patty melt to soak up all the beer we’d consumed. With the money I was making, I bought a turquoise-and-coral bracelet, a pattern that continues to this day—I love jewelry and clothes and shoes. I may have mentioned that my mother is partially to blame. I share her love of fashion but, alas, not her sense of frugality. I make the money, I spend the money. I have a wardrobe my daughter envies, which is just as well, since it will constitute the bulk of her inheritance.

I started attracting a local following and thought I was hot stuff. We had a strong music community in Carbondale, and as I got better, I performed at other clubs in town. There was Gatsby’s, a basement joint next to a pool hall whose owner sported a bad comb-over. Gatsby’s had a proper stage, free popcorn, and the coldest draft beer in town. Up the street a couple of blocks was Das Fass, a German beer house of sorts, decorated with steins and wooden kegs. Das Fass had an outdoor stage, an indoor stage, and a downstairs room that resembled a bunker, where I played solo for a while, until I got the bug for company and more sound.

I decided to broaden my horizons and add more players to my little scene. Jimmy could play the bass, and he’d made friends with a drummer named Dennis Conroy who had been in a group called the Cryin’ Shames. Dennis also played the tablas, which are hand drums originally from India. Let me just say right here that tablas are a bad idea. They have a distinct ring when played, and the ring can and needs to be tuned for each song key, which requires the pounding, up or down, of small wooden blocks on the side of the drum to adjust the tone. And Dennis was a perfectionist. Who would ever have thought that endless amounts of time could be spent between songs waiting for the drummer to tune? I took a major leap and went electric, hiring Jim’s friend Jack O’Boyle on lead guitar, which ultimately meant putting Dennis on a real drum kit, effectively ending the infernal tuning of the tablas. We were the Shawn Colvin Band. Rock ’n’ roll!

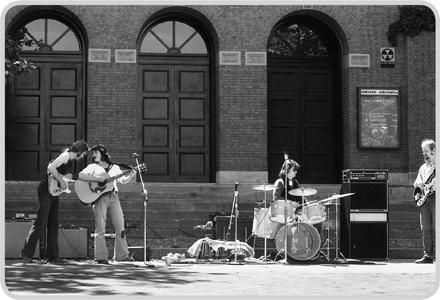

Shawn Colvin Band—Jack O’Boyle, me, Dennis Conroy,

and Brian Sandstrom—SIU campus, 1975

Our repertoire consisted of the same material I’d done by myself, with the addition of some Bob Marley, a few of Jim’s songs, and a lot of the new incarnation of Fleetwood Mac. At this point wardrobe was becoming key, and between Joni Mitchell and Stevie Nicks I was getting my look down. One New Year’s Eve, I was booked to play Das Fass, and all I could think about was what to wear. On the cover of

For the Roses

by Joni Mitchell, which had come out a few years back, she was wearing a green velvet tunic with matching green velvet pants that were tucked into a pair of tall, blond Frye boots. I managed to find the boots, but the velvet situation was more challenging. Being Barb Colvin’s daughter, I had some sewing chops and went on down to Fashion Fabrics, where the only green velvet available was a bright Kelly green, not at all like Joni’s sage green outfit. What to do? I went with brown, deciding that Joni’s vibe on

For the Roses

was decidedly organic, donned the boots, and was set.

All decked out, I went to do my gig, and between the first and second sets I got so drunk I actually could not play. This had never happened before. Looking back now, I can see it’s clear that my behavior was certainly alcoholic in nature, although I wouldn’t be able to make that determination for another ten years.

Although I’d had anxiety my whole life, I’d always found ways to manage it, but I was at an age, nineteen, when, biologically, depression can really kick in. And although I felt at home onstage, emotionally I was starting to unravel. Drinking wasn’t enough to keep me grounded. Neither was singing or my guitar at the foot of the bed. For one thing, making a living as a musician was just not done as far as I could tell. I knew lots of people, including my parents, who loved music and had talent for it, but none of them made it a profession except for the father of my childhood friend Ruth, who was our church organist in Vermillion. I was pretty sure I wasn’t going that route, but I didn’t know where I

was

going. I felt fraudulent.

That summer I’d been smoking a lot of pot, almost daily, which was just nasty stuff for me. It made me trippy and paranoid, but my older and therefore wiser boyfriend, Jim, was big on it, so we smoked. One night in August 1975, we got stoned and saw

Nashville,

a quintessential Robert Altman movie in which the heroine, a famous singer played by Ronee Blakley, gets shot. If pot makes you trippy, you most likely don’t want to be smoking and going to one of the typical seventies-era Altman films, brilliant though they may be, and this is particularly true if the singer heroine gets shot and you have visions of yourself as a singer heroine. When we left the theater, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the most pervasive sense of doom and terror. In an effort to feel safe, I made Jim take me to my parents’ house. But they didn’t know what was wrong either.

That attack subsided, but never completely, and I had the nearly constant feeling during the next few months that something terrible was going to happen, a visceral sense that even the ground I was walking on wasn’t to be trusted as stable. At times the panic would begin to rise and I’d have to leave wherever I was and run outside to breathe.

The bottom completely fell out that October when I happened to see a TV show about John Kennedy and the Bay of Pigs, called

The Missiles of October.

All that free-floating terror got sucked into a vortex of concentrated, specific horror: nuclear war. I became sure it was imminent. I couldn’t eat or sleep, and I saw signs of the impending holocaust everywhere. For example, at that time a Simon & Garfunkel song called “My Little Town” was quite popular, and there was a lyric in it that repeated over and over: “Nothing but the dead and dying / Back in my little town.” One morning I turned on the radio and those were the words I heard. I was sure it was a sign. It’s one of the things that can happen when the brain chemistry goes hinky, and extreme anxiety is often a component of depression. My brain can get stuck, and terrible, catastrophic thoughts loop around in my head, rooting me to the spot, waves of icy terror shooting down my limbs.

My parents tried their best to comfort me. I was extremely needy. I would call on them at all hours, when I felt like I was just going to lose my mind. At any given time—and it was fairly constant by this point—the terror was paralyzing. Their house felt like the safest place I could be. If I could get there, I could take up residence on the family-room couch, where I would sit for hours, but I couldn’t always get to their house. I recall being at my apartment once, and I was unable to get from my room to my car. I was too scared. I called home, and my dad answered. There weren’t any cell phones then—can you imagine? I mean, the last time I went to the ER, I took an ambulance and texted my friend Robin the entire time. (As I grew older, I learned to take my panic when necessary to the ER, but when I was nineteen, my parents

were

the ER.) I called my father, and he walked me theoretically out of the kitchen and to the front door. The plan was to get to the car just outside. We hung up. I got stuck in the kitchen. I couldn’t move. I didn’t understand how. I called back. This time I actually walked to the front door, but I had to walk back into the kitchen to hang up. I got stuck again. I called back. I remember talking to him and staring at my stacks of record albums on the shelves, the comfort of music a distant memory.

What the hell was going on? No one knew. I felt hideous. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep. I was immobilized. Finally my parents took me to a psychiatrist, who first killed the anxiety with a tranquilizer so rad that I didn’t care if the world blew up right then and there. Next he started me on Elavil, an antidepressant in the tricyclic family that is now old-school, but I’ll be damned if it didn’t work

exactly

in the time predicted—three weeks. Three weeks that I spent getting blurred vision and dry mouth and listening constantly to

The Hissing of Summer Lawns,

Joni Mitchell’s new record. It was 1975. One morning I woke up and the dread was gone. Gone. I was better.

I should have stayed on medication from then on, but one of the frustrating things about depressed people—and there are many, lest you think we don’t know—is that feeling better tends to convince us that there was nothing wrong in the first place. Like childbirth—you forget. But it’s unlike childbirth in that you want to deny that anything ever happened, so after a few months I stopped taking the Elavil with seemingly little consequence, but as I look back at the ensuing years of alcoholism, it seems likely that I was, at least in part, just trying to medicate the depression.