Diamond in the Rough

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

To Caledonia, Mimi, and Papa

Put your ear down close to your soul and listen hard.

—Anne Sexton

Contents

Who doesn’t have a bit of pyromania in them? There’s something thrilling about making fire—it’s primal, right? As a kid in rural South Dakota, I remember wandering one day out onto a vast, grassy field wielding a pack of matches from my father’s pipe drawer, with the express purpose of burning something. It seemed so inviting to light a fire or two. Almost as good as burning up an ant by letting the sun shine onto it through a magnifying glass. I made small piles of grass, set them ablaze, and stomped them out. Eventually, I couldn’t resist making multiple piles and my tiny fires, with the help of some wind, suddenly turned into one big one. I stomped for all I was worth, but it was no use, I had me a

fire

, and I went running to the house to tell my father, swearing with big wide eyes that I’d just

found

it, I didn’t know how it happened. He didn’t believe me, of course, but as parents will do at times when they know you’ve just gone through a rite of passage, like saying the dog ate your homework, my dad let it go and extinguished the fire.

Having learned nothing from this experience, I went on as an adult to continue setting fires. It’s true. Twice I’ve burned up memorabilia from relationships with fools who have broken up with me. One of them, a long-distance affair, quit me over the phone with the line, “I’ve got cats to feed.” In all fairness, this very short-lived “relationship” was mostly an illusion on my part, born of the simple desire to have a boyfriend. I’d met him at a gig somewhere and was smitten immediately. Adorable in a totally nerdy way, he played this card to great effect by wearing glasses he didn’t need, and I’m a sucker for that professorial–cum–Dennis the Menace look. He’d seen a video of mine and thought I had nice legs. Game on! He didn’t know what he wanted, but I did. Okay, so he still lived with his parents. And he was younger than me. I wanted a boyfriend. My philosophy tends to be that in the absence of a genuine relationship I am only too happy to invent one. Didn’t the simple desire to be with someone, in addition to mutual attraction, make it a fait accompli? Uh, no. There were literal and figurative miles between us, and try as I might, I could not make the thing fly.

In short order I wore him out by demanding attention he couldn’t provide, and he needed to feed the cats, of course. I decided to lay it all to rest by incinerating whatever I could find that reminded me of him. There was virtually nothing to burn—a few photographs and a cashed check I’d written him so he could come see me once. I set out a small cookie tin on the living-room rug of my apartment and lit my funeral pyre.

Just like when I was a kid, there was trouble. My carpet was made of synthetic fibers, and when the heat hit it, it started to melt. The rug was new, a remnant I got cheap at ABC Carpet and Home (the holy grail of decor), the color of the Caribbean, which I felt was a strong choice, especially with my pumpkin velveteen sofa. Very Renaissance. In horror, I caught the unmistakable odor of burning plastic, and with some oven mitts picked up the blazing tin as my rug seared and bubbled. You’d think I’d have learned my lesson, but no.

The next time I set fire to keepsakes from a lover was fairly recently. He drifted from place to place, which was romantic but hardly practical. On top of this there were children (both of us), an ex-wife (his), two ex-husbands (delicate cough), and midlife crises and stalled careers (across the board). But in my never-say-die fashion, I hung on. By God, I wanted a boyfriend. I was entitled to a boyfriend. It’s just as well if they live far away, because I can’t live with anyone. Another subject altogether. Anyhow, two years down that ever-challenging long-distance road—and let’s not forget I tour half the year as well—it was all over.

This having been a longer affair than that other one, I had plenty of things to burn up. Cards, letters, photos, locks of hair (not paper and stinky when burned, FYI). The jewelry I kept. Fortunate enough to have a fireplace this time, I was all set as far as the carpet problem went. The only remedy for my anguish was to torch the offending items. I tossed them into the fireplace, lit a match, and let the healing begin. Of course the flue was shut. Of course I couldn’t open it, since I depend on boyfriends for things like that. The house started to fill up with smoke. It happened to be the morning of my daughter’s eighth birthday, and we were going to have a party, so I frantically threw open all the windows and went running around trying to find fans. It was July, and later, at the party, no one could understand why the house smelled like Christmas.

All my fires backfired. But Sunny’s didn’t. Sunny is the arsonist in what is probably my best-known song, “Sunny Came Home,” and I’ve been asked more than a few times what was she building in her kitchen with her tools, what did she set fire to, and why? First of all, Sunny is me. Everything I write is through me, through my perspective. That realization is what helped me write songs in the first place. There’s nothing under the sun that hasn’t been said before, but no one can say what I have to say except me. Both Sunny and I went through a lot, I suppose, and came out the other side (at least I like to think Sunny was acquitted). She may have gone overboard a tad, but we are both of us survivors. I think it’s safe to say she was pretty pissed and burned the house down. Why? We may never know. But I may be able to offer some clues.

They gave me Dilaudid. They had to give me something. I was on a gurney in South Austin Hospital with a kidney stone, a broken heart, and an unrelenting, treatment-resistant depression. At least they had something for the kidney stone. Dilaudid, or pharmaceutical heroin. It was good stuff. One shot of it wasn’t enough to kill the pain, so they gave me two. Being a recovering alcoholic and drug addict, I now understood with new clarity why it had been such a blessing that I’d never tried heroin. Not only did the Dilaudid take away the physical pain, it made me euphoric. What depression? What heartbreak? I was high, of course.

Still, I held on to the possibility that maybe the Dilaudid would allow me to turn a corner and launch me into a state of emotional well-being as if by magic. Like the old theory that hypothesized if one got hit on the head and developed amnesia, then perhaps another blow to the head would reverse it. Like the way we attempt to fix the television’s lousy reception by banging our fist on top of it.

Maybe this last kick while I was down, after being dumped, after sinking into the black hole, maybe this would be my salvation. Maybe the agony from the kidney stone and the sweet relief of the Dilaudid were a metaphor for the absolute bottom of the pit I’d been in, maybe the Dilaudid would miraculously heal my heart, fill it up and over, nudge the neurotransmitters in my brain back into rhythm, jolt them out of their amnesia, make them remember how to work again, so that when I woke up the next day, my very being would be rebooted. Restored to its original settings.

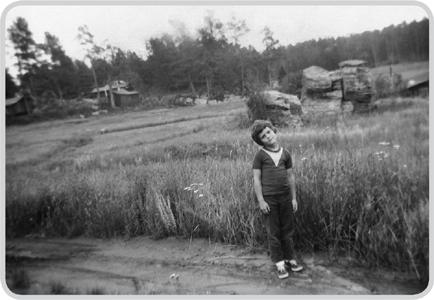

South Dakota, 1960

It’s like ten miles of two-lane

On a South Dakota wheat plain.

I was born on the prairie, in southeastern South Dakota. If you want wide-open spaces to throw your imagination at, the Great Plains are the place to be. When I was ten, my father decided we should live out in the country (as opposed to Vermillion, our bustling town of six thousand back then), and I used to walk the fields out there for literally hours in my Beatle boots and my mother’s black leather jacket and pretend I was a Beatle. I guess I see my life as pretty much starting when I heard the Beatles. It was in this house I listened to “Not a Second Time” over and over on my record player until my father begged me to stop. Even then I was sophisticated enough to go for the deep tracks.

I had a very, very best friend named Ruth Noble, and we were misfits together, considering ourselves a little superior in our quirkiness. We didn’t care about dolls or horses; we liked puzzles and junior church choir and Mr. Wizard. Her older sister, Jane, was the keeper of the Beatles albums, so Ruth’s house was better, but you couldn’t just grab a record and play it. Permission was required, and often denied, and I always had one eye out for Jane and the possibility of listening to the Beatles. I just lived for it.

It wasn’t as though we were immune to the pop-idol syndrome—those moptops were awfully cute. But it was the new sound that got to me. Up till then I had heard only church music and my parents’ record collection, which consisted of things like the Kingston Trio, Pete Seeger, and sound tracks for

Porgy and Bess

and

The Sound of Music.

There was a novelty song called “Wolverton Mountain,” which was just insipid and silly, and my folks played it to death. If we could get Top 40 radio, I didn’t know about it. However, we did have television—and we watched Ed Sullivan. Enough said.

So, as a Beatle, I would tromp around the fields as if I owned them, and maybe I did. The plains coaxed my dreams and fantasies with their bleak nothingness. The unending earth and sky were like a blank canvas, inviting any idea to be outlined and filled in. And the storms of the Midwest are like nothing else.

The Wizard of Oz

had it right. You can watch them come in from far away, even see the clear definition of receding blue pushed up against gigantic blackness, and wait for the first wind as the dark clouds pass over, bringing wild rain and thunder and lightning. These storms frightened me as a kid, and I’ll never forget my father, loving them as he did, taking us out on the porch during those fantastic midwestern tempests and telling us about the different storms he remembered, from his youth right up through being in the army. And so I began to love storms, too.

Vermillion was not a town of diversity. I saw only white people for eleven years. We went to school, went to church, rode bikes, and pretended. My daughter goes to theater troupe and therapy (a chip off the old block), while her friends go to soccer practice, voice lessons, and the Shambala Center, and summers consist of all manner of camps. There was none of that. We were not overscheduled, because there was nothing to do. We were not overprotected, because there was nothing to fear. We walked and biked to and from school and the pool and one another’s houses and played tag until we were called in after dark. During the winter we stayed in or sledded down some pitiful hill or skated on the river. Our Main Street sported Jacobsen’s Bakery, the Tip Top Café, and the Piggly Wiggly. To get to our house, you turned right at the bowling alley.