Diamond in the Rough (20 page)

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

John and I won two Grammy Awards that night. One for Record of the Year. And Song of the Year—that’s for

songwriting.

Bonnie, it just got better.

And

I was carrying around a little something extra that night. Guess who’s coming to dinner? And breakfast and lunch? For the next eighteen years?

The big night, 1998

(Photograph courtesy of Lisa Arzt)

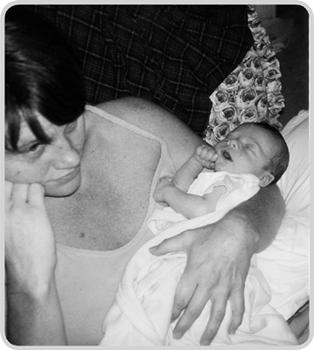

Me and Mario Erwin, baby daddy, 1996

(Photograph courtesy of Alex Erwin)

I believe I have pulled a major coup.

I believe I have boarded up the zoo.

I believe I have dropped the other shoe.

And there’s nothing like you.

In 1996, just as I finished

A Few Small Repairs,

I met Mario Erwin, a freelance photographer–turned–graphics salesman for a local Austin outfit. A mutual friend and her fiancé introduced us at the lake. Mario was going to take us all waterskiing. Although he hailed from Arkansas, he was of Italian descent and had lovely olive skin and big, bright, blue eyes. He was compact and sinewy, like my father, and his style was no-bullshit, wry, sarcastic. I hadn’t dated in about a year, and when I met Mario, I thought,

Well, I could sleep with this guy.

He called the next day and asked if we could go to dinner and did I want to go tomorrow or the following weekend? “The sooner the better,” I said. “We might as well find out if we like each other.”

We liked each other. In fact, Mario announced to me that same week that he liked everything about me—shouldn’t we be an item? It sounded good to me. I was lonesome. This might have been the right time for me to have played the field, but I’ll tell you, that concept eludes me. I don’t get it. Does that make me a serial monogamist? Or just a one-man woman? I even tried to suggest we not be exclusive right at first, sensing that my habit of diving headfirst into romances within minutes might be a problem. But Mario wouldn’t have it. I was flattered, I liked being wanted, and I was only too happy to be tied down. Mario had a boat. I had a dock. After a couple of dates, he put his boat in my dock—and yes, I get the symbolism.

My niece Grace was about a year old by then. I was in love with that child; I even felt partial ownership. And part of me felt lacking. I was the older sister, and Kay had taken the leap into motherhood first. Well, damn it, if she could do it, so could I.

I’d always had a difficult time picturing myself as a mother. I spent a great deal of my life resenting my folks for all their failings as I saw them. Part of me thought I could best them in the parent department, and part of me knew I had set impossibly high standards. I didn’t have pets because I traveled too much. I couldn’t keep a plant alive. I liked that I could spend an entire day if I wanted to just hiding from the world. Before I got sober at age twenty-seven, I was basically surviving. Afterward I began to be comfortable in my own skin. I could viscerally feel myself making up for lost time. I loved choosing what I would eat, loved that I had my own coffeepot, my own bed, my own apartment. I took myself to movies, things like that. Simple pleasures, more peace, fewer voices.

Fast-forward several years down the road. I’d had my fill of what eventually felt like a selfish lifestyle, and I remember thinking that if I were to have balance I was either going to have to have a child or devote myself to a cause. Something in me yearned to give. And meeting Mario and Grace almost simultaneously sent my biological clock into Oh. Ver. Drive. I’d made records, I’d traveled the world, I’d already been married once, and I was forty. It was now or never. When I got off tour at the end of the summer in 1996, Mario presented me with a back porch he had built himself onto the house on Scenic Drive, along with a diamond ring. We got married October 19, 1997, and by Thanksgiving I was pregnant.

Pregnant at Lilith Fair, June 1998

(Photograph courtesy of Lisa Arzt)

On the heels of

A Few Small Repairs,

the record company asked me to do a Christmas record. I couldn’t see my way clear to making sense of the idea until I remembered a book I’d been given when I was eight years old. It was called

Lullabies and Night Songs.

And while they weren’t Christmas songs, I thought I could probably blend those lullabies with lullaby-like Christmas songs, given that Christmas is about a baby being born and all. There was something in the way Alec Wilder voiced these songs for the piano. They reminded me of Aaron Copland. Beautiful and odd. It was summer, and I was eight and a half months pregnant when I recorded

Holiday Songs and Lullabies.

We made it in Austin with my keyboard player, Doug Petty, producing. Doug had owned the same book as a kid. The morning of July 24, 1998, I went into labor, and our daughter was born ten hours later, at 6:00

P.M.

, with “A Whiter Shade of Pale” playing in the background.

We took her home after only one night in the hospital—I was anxious to be a “real” mother. On

A Few Small Repairs,

I had a song called “If I Were Brave” where I asked, “Would I be saved, if I were brave and had a baby?” Well, yes and no. There is no rescue as I once imagined it, no secret answer, no one safe place. I think it’s the being brave that saves us, maybe. Is it brave to have a baby? Oh, without a doubt.

When did I know that postpartum depression had set in? I was overwhelmed, teary, completely thrown by this stranger in my house who required my constant attention, up to and including latching itself onto part of my body for nourishment. Does anyone talk about this, really? It isn’t that I didn’t love her or couldn’t bond with her. I felt deep empathy and responsibility for her and cared with all my heart. But I was awfully scared and unfamiliar with everything that was asked of me as the mother of a newborn. Life as I knew it was over—it was that simple. There were no off hours or holidays with which to be completely selfish. As one of my sister’s friends said, “You’ll never sleep the same way again.” Nothing would ever be the same again. My body and even my face looked different. The sky, the trees, the very air I breathed seemed to change.

A month after the baby was born, which seemed like an eternity, I got to go out with my sister. It was my first outing since the birth. Neil Finn of Crowded House was in town. We tracked down Neil and his wife, Sharon, at a restaurant. I must’ve looked like a deer in the headlights, because Sharon took my hand and told me that Neil’s brother, Tim, had just become a father. “Oh, wonderful, how are they doing?” I asked with false gaiety. “They’re shattered,” she said, and I felt the utmost gratitude and relief. Someone told the truth. A newborn baby is a terrifying thing to own. It seems to me only those with the most superior emotional upbringings or those who are just blessed with the gift of nurturing can make the transition into parenthood easily.

Callie at two days old, July 26, 1998

(Photograph courtesy of Mario Erwin)

And the colic—oh, the colic. My sister came over one day early on and gave me the official diagnosis. The baby cried a lot. I could soothe her, but only if I balled her up in the sling, put my little finger in her mouth to suck on, and walked. And I don’t mean around the house. I had to go outside. It was August in Austin. I might as well still have been pregnant, given her proximity to my body. The sweat would pour down my face and mix with the tears as I racked up the miles in our neighborhood. She would stop crying, and I would trudge along like a soldier. She would have no part of a baby carriage or a stationary swing or a vibrating seat or a cradle. She wanted back in, basically, and I didn’t blame her. I wanted her back in, too. We weren’t ready for this. She didn’t nap for long stretches, and she ate like a horse. At least that’s one thing I knew I was doing right—she was getting fat. I was just

staying

fat. Deep down I wondered if I had made a mistake. I had buyer’s remorse again. I like loopholes and return clauses and escape hatches. She didn’t come with any of those. I had wanted her more than anything, but when she really became mine, I freaked out. I didn’t know how to live in service to anyone else. I had lived for myself up until then. I did what I wanted, got what I wanted. And I knew there was something fundamentally empty about the way I was living. When push came to shove, though, now that the deed was done, I was dubious. Mario had had kids before. He told me that he used to look at me before she was born, all glowing with pregnancy and promise, and think,

She hasn’t got a clue.

He was right.

I adjusted. What could I do? I became her mother. I named her Caledonia, because I wanted to call her Cal—after Calpurnia in

To Kill a Mockingbird,

after Cal in

East of Eden,

after the song “Caldonia.” She became Callie. I barely worked for her first year, and we got to know each other. She was mine, and I was not going to fuck it up. She breast-fed until she was two and a half, and the only thing that finally put an end to it was the day she held my nipple like a cigar between her back teeth à la Groucho Marx, looked up at me, grinned, and said, “There’s a hair on it.” I weaned her that day. Her first word was “Dada.” Mario took it upon himself to peer into her face and repeat, “Dadadadadadada,” ad nauseam, and it worked, by God.

Her daddy taught me how to burp her—I patted her gently while she fussed after a feeding, and he, having had two other children, grabbed her, threw her over his shoulder, and gave her back a few good whacks. She belched immediately and was happy as a clam. Her daddy fed her, changed her, bathed her, read to her, took her to the park, put her to bed. He gave her language she still uses: “I’m confuzzled,” she’ll say, or, when not quite up to snuff, “I’ve got dibucus of the blowhorn today.” When I ask her to pick up her stuff, she says, “Make me, punk.” That’s her dad.

He shops with her and tells her what colors he thinks suit her, and this means the world to her, coming as it does from “a boy.” “I’m in love with that little girl,” Mario told me when she was days old. She is my first and only, but Mario has been around that block. Callie can’t throw him like she can throw me. He’s quick to see the drama and laugh her through it. She calls him “Sir Talksalot.”