Diamond in the Rough (18 page)

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

As I mentioned earlier, one of the artists who really taught me the most about relating to an audience, and about being a performer and a songwriter, was Greg Brown, one of the first artists I ever opened for, back at Passim. I’d always loved his tune “One Cool Remove” and liked the idea of doing it with my friend Mary Chapin Carpenter. I also covered the Band, Jimmy Webb, and “Killin’ the Blues”—that has-no-rhymes gem by Roly Salley from my days with Buddy—and a great song called “Window to the World” by a Tennessee band called the Questionnaires, led by Tom Littlefield. Tom and I co-wrote a song called “Trouble” that I would record on my next album.

This was a full, joyous time in my life. Simon and I got married in 1993 in the desert out at Twentynine Palms in Joshua Tree National Park. I’d now made three records. Tours were launched for both

Fat City

and

Cover Girl,

and Simon managed and did sound for them. I’d finally gotten used to that aspect of my job; in fact, I was more than used to it—I was loving it. Larry Klein, Steuart Smith, and I formed a trio for the road, and it was the best band I ever had.

We called ourselves the Masters of Rhythm and Taste, and we were a lean, mean outfit. I’d never felt so at home musically. There was just enough sound, and every note and beat counted; there was no fat to trim, no drums to sing over—Steuart said we were wearing drummer repellent. The essence of each song had to be captured by just the three of us, and to my ears we sounded fuller than an entire orchestra. There was magic and mojo among me and Steuart and Larry, both onstage and off. We were friends and bandmates, a perfect little microcosm of artistic and social heaven. I was with Simon, so the likelihood of road-induced hanky-panky was nil. The three of us were tightly bonded through our love of music, of course—and a thoroughly sick sense of humor.

The aforementioned Rudy Ray Moore

Zodiac

tape was required listening on the bus, post-show. I can’t even quote it here—it’s just too blue—but it decompressed us and set the stage for whatever movie we might decide to watch. And watch repeatedly. Steuart and Larry were fans of

The Bad Lieutenant,

a Harvey Keitel film so depraved it was barely watchable. I preferred a PBS special called

The Donner Party,

a perky documentary about cannibalism. Thereafter Steuart referred to our backstage cold cuts as “Donner party platters.” While watching

Alien,

Steuart had the bright idea of slowing the film down frame by frame just at the moment the creature shoots out of the egg and attaches itself to John Hurt’s face. He claimed that it was all done with raw chicken.

Steuart was extremely picky about movies; his guru was

New Yorker

film critic Pauline Kael. We all loved Martin Scorsese.

Raging Bull

and

Goodfellas

were staples on the bus. (I met Ray Liotta one time and asked him to please say, “Karen,” just once. He did.) I brought

The Last Waltz

and

Casino. Casino

might not have been as perfect as some other Scorsese films, but it has that great Scorsese rhythm along with a killer sound track. About a quarter of the way through it one night on the bus, Steuey, who’d had a little wine, stood up, slammed down his glass, and muttered, as he stomped back to his bunk, “It’s sloppy, it’s mean-spirited, and it’s

shit.

” It may have been when Joe Pesci stabbed a guy in the neck with a fountain pen.

About midpoint during our show every night, Larry and Steuart would go offstage so I could do a couple of songs by myself. I had a standard joke that I would tell about their having to leave the stage to be treated by the medical staff because they were drug addicts. I explained that I was a responsible employer and wouldn’t force them to go out on the street to satisfy their habit. One night while I was saying this, Steuart rode a bicycle behind me across the stage.

Before we went on each night, Larry would pull me aside. He would solemnly take my hand, turn it over, and put his finger in my palm. “Shawny-Shawn-Shawn. Here,” he began, “here is the audience. You must put them here. And then”—and as he said this, he would subtly tilt my hand from side to side—“you must play with them. You must always give them something,” he would say, “but do not give them everything.” At a small club in Italy, we once did a thankless, awkward show where only members of the press were invited. Most of them didn’t speak English, and I wager most of them didn’t want to be there. I was tired, and I was not in the mood. When we went on, I stood very still and closed my eyes, never opening them once throughout the entire performance, giving probably the most lackluster show ever. Backstage afterward, Larry threw up his hands in mock despair and wailed, “But you must give them

something

!”

Larry’s alter ego was “Señor de la Noche,” which loosely translated means “Lord of the Night.” In a former life, while working with some Latin jazz players in the eighties, he was so christened during all-night cocaine binges. Señor de la Noche would appear to us from time to time, to say in a thick Spanish accent, “I know exactly what you mean, my man.” Or, when particularly nostalgic, he might sigh wistfully, “Ahhh,

la cocaína

—the laaady …” Señor was a bit of a prankster as well, often daring us, for a reward of “two hundred pesos,” to confront total strangers about their clothing or hair or sexual habits, usually in airports when we were forced to abandon our beloved bus and fly. When that was the case, Steuart, who loathed flying, would ingest a concoction he called his “atta-boy cocktail”: a tranquilizer, Ativan, washed down with a martini. Or two. After a long flight from L.A. to Melbourne, Steuart emerged from the plane completely disheveled and asked in all seriousness, with just a hint of panic, “Does anyone else feel upside down?” Señor de la Noche wearily replied, of course, “I know

exactly

what you mean, my man.”

One of the great friends I made in California was David Mirkin, who loves music more than anyone else I know, except maybe Steuart. Dave can tell you not only who sings lead on any Beatles song, he can tell you who breathed where. Dave is divinely funny, ridiculously so, and is responsible for launching my cool factor into the stratosphere by getting me to voice a character on

The Simpsons,

which he executive-produces. I was Rachel Jordan, a Christian rock singer. It was also Dave who got Garry Shandling to come down to my gig one night. Garry asked if I would appear on his series, and that’s how I got on

The Larry Sanders Show.

Meanwhile, despite the fun things I was doing and the good friends I was making, I had to wonder what had possessed me to relocate to California. Yes, of course I loved the flea markets, a shopaholic’s true nirvana, but if you’re from the Midwest, you just can’t feel at home without a good thunderstorm now and then, and they didn’t exist in L.A. And, of course, there was the Northridge earthquake in 1994. Our friend, Danny Ferrington, an ace guitar maker who hails originally from Louisiana and has a voice registering somewhere between those of Minnie Mouse and James Carville, took this opportunity to defend his gas-guzzling SUV, saying, “When the shit hits the fan like this, I can get home!” Meaning he could off-road down Lincoln Drive to his apartment in the Palisades. I did everything wrong during that earthquake. As soon as the house started pitching like a washing machine at 4:00

A.M.

, I ran directly to the back door and panicked. Not recommended. Then I ran to the front door screaming while every car alarm for miles went off. That seismic party, along with the lack of weather in L.A., put me over the edge.

I had a gig in Austin and decided to look for a house there. Simon was on board for the move. Austin was a music town and had great food, no earthquakes, and no shortage of thunderstorms. In no time flat, I found my dream home, really just a

Leave It to Beaver

house but

right across the street

from Lake Austin, with a

boat dock

to boot. I threw my down payment at it, and we loaded up the truck and moved to Scenic Drive—yes, that was the name of my street. Scenic bloody Drive. Oh, Lord, oh, Lord, why in the name of God did I ever sell that house? You don’t sell a house on Scenic Drive; you hold on to it for dear life so you can retire in ten years. Simon went on tour with Richard Thompson, and there I was, sitting in a four-bedroom mortgage. The house on Scenic Drive turned out to be a house of cards.

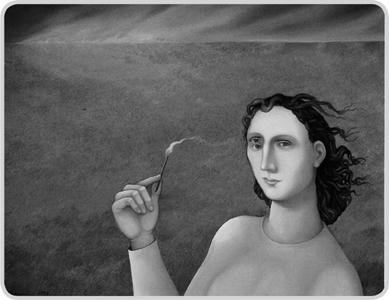

Julie Speed’s

Setting the World on Fire

oil painting

(Photograph courtesy of Julie Speed)

Line ’em up in a row.

Gunshot—ready, set, go.

During our first few months in Austin, I sat with a bunch of guitars and notebooks in my “writing room,” which was actually just a bedroom upstairs overlooking the water. I’d gaze out at the lake, trying to take in my good luck. I’d never had a writing room before. Shouldn’t I be prolific and brilliant now that I did? It was no use. When I write, I like to empty my mind and focus in on a feeling or a rhythm or a melody. But my head was spinning. Why, oh, why had I moved away from New York, a hotbed of edge and sophistication and artiness where a weird South Dakota girl like me seemed downright normal? What was I doing in a neighborhood living among doctors and lawyers with no Korean delis, no Two Boots Pizza, no MoMA? Where I had to

drive

to get anywhere? How could I have left my crazy friends, Stokes and Kim? Oh, I stared at that lake and came up empty. I was neck-deep in the biggest commitment I’d ever undertaken, becoming a homeowner. Wedding vows were cake compared to this. There was nothing to do but write about it: “Go jump in the lake, / Go ride up the hill, / Get out of this house.” Yes, the starting point for my next album was inspired by buyer’s remorse, and it would take down my marriage.

It’s rather glib of me to blame the failure of my relationship with Simon on a house, but the bottom line is that I wasn’t ready for either of them, the husband or the house, and it certainly wasn’t the first time, nor would it be the last, that I ran from commitment.

We’d had our troubles even in California. Simon liked his pot, and I wasn’t woman enough to just let him. It irritated me when he became stoned and got dry mouth and talked slowly and acted spacey and giggled over nothing. One night at a party in L.A., he wandered off for a while, and I knew it was demon pot that got him. Sure enough, he returned to where I was sitting in the garden, and I was grossed out. Seeing my boyfriends in altered states threatened me; I wanted to be able to relate to them at all times. Of course I could have attempted a little sense memory from back in my druggie days, but I didn’t. I was annoyed, and Simon agreed to leave the party and call it a night. As I drove us home, I felt a little sheepish for coming down on him and suggested we rent a movie. He agreed apprehensively, not sure if he liked me, but then slowly his whole face lit up. Still foggy and silly from the reefer, he exclaimed, “Oh! Could we get a comedy?” We got Monty Python, a stoned Englishman’s nirvana.

But we’d had lovely times, too. In the L.A. days, Simon rewrote the words to the Crowded House song “Weather with You”:

Walkin’ round the room in my favorite sweater

At 209 Rennie Avenue.

It’s the same gear, but everything’s different.

We got a garden and a bar-b-que.

Kay is cookin’ in our kitchen,

Jane’s Addiction on the radio,

Caesar salad at the Souplantation,

Simon and Larry say, “Oh, nooo.”

My sister, Kay, had lived not far down the road from us in Venice. She worked as a sound tech on films. We became addicted to the Souplantation, an all-you-can-eat cornucopia of salads and soups. We would stuff ourselves there and went so often that Simon began to dread dinnertime. Twice we went to Australia to visit Simon’s son, Tom. Fond, fond memories. Simon was a love. He still is. Just last summer Callie and I took him and Tom out on Lake Austin for the day.

But back then I felt trapped and completely out of my depth at the prospect of committing to forever and building true intimacy. I found that living with someone wasn’t something I could put my best self into. I felt suffocated. I didn’t like sharing or compromising. Simply put, I was childish. The thrill of the chase and getting married had worn off, and, of course, some real issues came to light, both his and mine. I found myself unwilling and unable to work them out, and so between the husband and the house, I kept the house and fled the man by asking Simon to move out. We had been married two years.

It was back to the writing room, or the drawing room, or even the rubber room perhaps. At any rate, I hadn’t made a record of original material in almost four years. The folks at Passim would surely not approve. It was time.

I had written a few fragments of music and lyrics and had finished two whole songs, “If I Were Brave” and “New Thing Now.” But I needed help to write more material, and it occurred to me that maybe enough water had gone under the bridge for John and me to take a stab at writing again. We hadn’t worked together in five years and probably hadn’t spoken in three, which allowed me to get some distance and move on both personally and musically. I called him one day in 1994, and the next thing I knew, he had flown down to Austin to meet with me.