Controversy Creates Cash (27 page)

Read Controversy Creates Cash Online

Authors: Eric Bischoff

Rey’s argument was, “Wait a minute, in Mexico, that’s who I am.”

“Yeah, but you’re not in Mexico anymore, so guess what? You’re going to lose the mask.”

I actually tried to be more diplomatic than that, but it came down to push comes to shove. I had to stand my ground. He lost the mask in a Hair versus Mask match at

Superbrawl IX,

when Mysterio & Konan were defeated by Nash & Hall.

But losing the mask was hard on Rey. He didn’t really embrace it. These days, he wrestles with it on in WWE.

Booking

By this time, Kevin Sullivan was our lead booker. Ric Flair hadn’t worked out, and gradually Kevin assumed a bigger role in the committee in charge of the wrestling storylines.

Dusty Rhodes had brought Kevin in as an assistant booker, a kind of balance to his talents. Dusty knew that he was really good building up babyfaces. He also knew that to have a good babyface, you need effective heels. Kevin was one of the few bookers or wrestlers out there who really understood real heat and heels. Kevin was a little wacky, and some of his ideas were way, way out there, but he knew what it took to create real heat, and not just a Pavlovian response, which was what we had been doing up until that point—and quite frankly, what I see mostly today.

204

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

With the start of

Nitro,

I took a much greater role in booking. I felt I understood what the show needed, and had learned or absorbed enough to make it happen. The top third or so of the card was under my direction. Kevin and the rest of the booking committee took care of everything else.

Hogan as Heel

At the beginning of 1996, I began thinking a lot about Hulk Hogan as a character. His character, from my point of view, had played itself out.

I wasn’t as dependant on Hogan as I was in 1994. Our contract required him to be used a certain number of days a year, and gave him a fixed amount for each Pay-Per-View. That was already in the budget and wouldn’t be changed, one way or another. We’d already gotten our value from him, positioning our brand as a good advertising opportunity. I think we only had another three or four dates left in his contract.

But Hogan was a tremendous performer, and it made sense to try and do something more with him than just pencil him in. He was an enormous resource—if we could tap it.

The more I thought I about it, the more I came back to one idea. Hulk Hogan was one of the all-time great babyface characters.

What would the impact be if he turned heel?

Handled correctly, it would be huge.

By this time I had a good relationship with Hogan on a personal level. So I called him and said, “Hulkster, what are you doing next Tuesday? I’d like to come down to Florida and run some ideas by you.”

“Sure, brother. Come on down.”

So I flew down to Tampa, rented a car, and went over to his mansion on the beach. We sat down, had a beer, shot the shit for a while, and got caught up. Everything was great.

PRIME TIME

205

Then I walked him through the idea that he might turn heel.

He stroked his Fu Manchu. He rested his chin on his hand and continued to stroke his Fu Manchu for what seemed like twenty minutes. Then he said, “Well, brother, until you’ve walked a mile in my red and yellow boots, you’ll never really understand.” And with that, he looked at his watch and said, “I’m sorry, I’ve got to go pick my kids up at school.”

He showed me to the door.

-----------------------------------------

------------ -----------------------

-----

-

7

The Revolution

Takes Hold

The War Within

Germination

Nitro

revolutionized the pro wrestling business in many ways, changing the target audience, adding realistic storylines, creating more reality-based characters, emphasizing surprise as an important element to every show, and taking viewers backstage as part of the storytelling process—many of the things we take for granted today were done first on

Nitro

.

And if there was one angle that epitomized that revolution, that summed it up and embodied it better than all others, it was nWo—

the New World Order.

Actually, the New World Order was a lot more than a simple storyline. It was a cult, a virus, a revolution. It was reality TV before reality TV was invented, or at least popularized. When the nWo wrestlers attacked WCW, they took the audience’s real-life emotions and turned them into wrestling weapons. The audience re-208

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

warded us with some of the highest ratings cable programs have ever received.

Scott Hall

The seed of the idea was planted when I heard Scott Hall was interested in coming over to WCW.

Scott had worked with Verne Gagne in the AWA, teaming up with Curt Hennig. He’d left before I got there, but I knew his character. Scott had also been in the WCW for a short period while I was there. From there he went over to WWE, where I’d watched him as Razor Ramon. He was a tremendous performer, but he also had a reputation for stirring the pot behind the scenes.

Scott was friends with Diamond Dallas Page, who lived near me and who would occasionally stop by on a Saturday afternoon for a beer. One Saturday, Page came by and we started shooting the shit.

He said, “Hey, I’ve been talking to Scott Hall and Kevin Nash.

They’re interested in making a move.”

Nash, then known as Diesel, had also wrestled in WCW for a brief time before going over to WWE. While he usually played a heel, he had held the championship title for about a year, from late 1994 to 1995. He and Nash were good friends.

Page said they were miserable. They weren’t happy with the politics, their pay—you name it.

By the way, that was no reflection on anything that was going on in WWE—at the time, I don’t think anything could have made those two happy.

Anyway, they made it clear that they’d be willing to make a jump. Not knowing what the situation really was and whether I could trust them, I used Page as a go-between. The pitch was, “You come over here and you’ll get a guaranteed paycheck, and you’ll work less.”

THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

209

Compensation

As well as we were doing in 1996, WCW still did not have a great licensing and marketing business. In WWE someone like Nash or Hall could make considerable money from their cut of the licensing and merchandise. We didn’t have that, which was one reason we had to continue guaranteeing contracts. In some cases, the amount was actually less than the performer might have made in WWE, but the fact that it was guaranteed meant a lot. We wanted to eventually build to the point where we could change our compensation plan to something along the revenue-sharing lines; we just weren’t there yet.

Of course, at the time the WWE compensation plan really was: you got paid whatever Vince McMahon decided to pay you that day.

The fact that we were on the road a lot less—we had no plans to go beyond 180 days, while the WWE was on the road 250—was also a big draw. If you’re a performer, you’re thinking, I can make X

working with WWE, but I’m on the road all the time, not spending any time with my family, and I’m breaking down. I can make X plus 10 percent and go to work for WCW and work half the time.

What would you do?

A lot of the guys who came over to WCW were attracted by the schedule, not the money. Most of the guys thought that if they stuck with WWE, they’d make more money in the long run, because of the revenue-sharing. But our lighter schedule was a real draw.

Despite what the WWE would like people to think—and despite what the dirtsheet writers loved to say—I didn’t steal these guys. Any time talent went from WCW to WWE, nobody said Vince McMahon stole them. Whether it was Kevin Nash or Scott Hall or Vader or Ric Flair, it wasn’t stealing if they left WCW. It was only grand larceny when someone left WWE for WCW—especially during this period.

Anyway, we ended up doing a deal with Scott Hall, and very shortly afterward, with Kevin Nash. I knew having them together represented a terrific creative possibility—but I had no idea what it was.

210

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

Disrespect

I looked at Scott and Kevin and said, “What’s my story with these guys?”

The word had already leaked out that they were coming over. It had to, since they had to give notice. So I couldn’t surprise anyone with it, the way I had with Lex Luger.

There was, however, anticipation, and the fact that both had been with the WCW before becoming stars in WWE. So I decided to build on that.

Scott came over on May 27, 1996. I picked him up at his hotel.

We were in Macon, Georgia, for the show.

I wanted to get into his head and find out where he was at. I’d heard a lot of negative things about Scott, that he was a shit dis-turber, very problematic, very manipulative. Scott’s chemical history was also pretty well known to just about everyone in the business. I knew I wasn’t getting a solid corporate citizen.

The morale in our locker room was fairly high. For the first time, these guys were on the winning team. I’m not saying everybody was happy with every little thing, but for the most part the morale was good. I knew that. I also knew what a guy like Scott Hall could do if he was disgruntled. I had enough politics going on with Hogan and Flair.

On the drive to the show, I made it clear to Scott that if he was going to come in and turn the place upside down, I wasn’t going to tolerate it.

Scott, to his credit, was very humble and assured me that wasn’t the case. He meant it, at the time anyway.

I didn’t share my plans with him, even then.

When we got there, I wrote his interview for him. I wanted people to say,

Holy shit, this must be real, because I’ve never seen anything

like this before.

And I remember thinking,

God, I hope this guy can

pull this off.

My idea was for Scott to come down in the middle of a match, in a way that appeared to be spontaneous and unannounced. He’d THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

211

walk down from the audience, grab a microphone, create a disturbance, and spout off. He was a rebel, pissed off, coming back to WCW with a chip on his shoulder.

The chip was that he had been disrespected at WCW. The company had held both him and Kevin back, and now they wanted re-venge. They were the Outsiders. They had reached a level of stardom at WWE and decided to come back because they’d been disrespected.

That was the storyline, and Scott laid it out in his promo. He told the audience that he’d been disrespected and intended to fix that by kicking butt. He was coming back next week with his big friend—Nash, though his name wasn’t mentioned—and they intended on taking no prisoners. He looked angry, and the audience responded as if he really was.

The beauty of the promo—if I may pat myself on the back—

were the questions it raised. Who was coming with him? What would they do? How? What would the consequences be? What’s their agenda?

That wasn’t by accident. I’d figured out that the best way to tell a story was to get the audience to ask themselves, What’s going to happen next?

If they wanted to know, they had to tune in and find out.

An Amazing Bump

Kevin Nash answered some of the questions the next week, just by showing up. Viewers were wondering how far we were going to take things, and the answer was,

Further than they thought.

And I almost didn’t survive it.

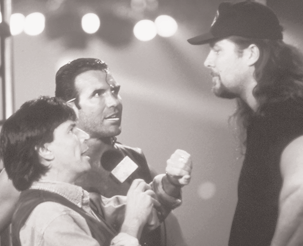

The bit began when, at

The Great American Bash

in Baltimore in my role as

Nitro

announcer, I stood on the stage and introduced Scott Hall.

“All right,” I said in my most sardonic voice, “where’s your big buddy?”

212

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

----------------------------------

------ ------------------

--------

--

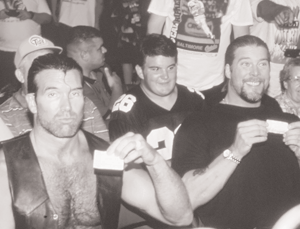

After they were banned from WCW events, Hall and Nash brought tickets, just so they could be thrown out.

Kevin Nash came out and yapped at the crowd. Scott punched me in the stomach to double me over, then Kevin hit me with a powerbomb.