Controversy Creates Cash (29 page)

Read Controversy Creates Cash Online

Authors: Eric Bischoff

Our nWo third-man scenario made me realize there was another important element to storytelling as well: anticipation.

Most people underestimate the emotional value of anticipation, but I think it’s the most important element of all. When you are a young child, you anticipate the holidays, your birthday, etc. By the time you’re twelve or fourteen years old, you’re anticipating your driver’s license. It’s akin to independence. The amount of anticipation that goes into that sixteenth birthday is immense. Then it’s graduating from high school. Going off to college. Then turning twenty-one. And so on.

THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

221

Does It Have the Elements?

Once I could articulate it for myself, I started preaching the formula to my writers. I called it SARSA: Story, Anticipation, Reality, Surprise, Action.

Not every idea can be equally strong in all five elements, but that’s the goal. “When all five are there in a big way, we can live off that idea for two or three years,” I would tell my writers. “If it has four out of the five, it’s important enough to book into a Pay-Per-View. If it has three out of the five, it might get us through a week or two. If a story doesn’t have at least three of the SARSA elements . . . I don’t want to hear it.” My favorite question when a writer brought an idea to me was,

“Where is it going next week?” I wanted the writers to have an arc—a beginning, middle, and end. We wanted a climax, a payoff for the audience—at a Pay-Per-View, if the story was good enough.

Often I would say,

Tell me what you want to have happen a month

from now and work backward.

The formula worked really well. It became our mantra. I use it myself to this day.

Judging whether a story had SARSA was a gut thing. It couldn’t be an exact science because some of it was subjective; I could kind of feel it when it was right. But another thing I did was check out how things were connecting with the crowds. I had a habit of finding places to hide during the shows, just watching our audiences. As time went on, it got more difficult to do this because I was so involved in the television show, but I could still do it at house shows.

I’d watch the crowd and listen to what they had to say.

Hook and Drag

It wasn’t an accident that the third-man storyline climaxed at a Pay-Per-View. Pay-Per-Views have been critical to the industry’s business model since Vince McMahon took over World Wrestling Federation 222

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

and took it national. Traditionally, Pay-Per-Views have featured the biggest matches of the year.

One of the things that we did on

Nitro

—and I took a lot of criticism for this—was put Pay-Per-View–quality matches on free TV.

The stories that unfolded weekly on television—whether they centered on Ric Flair and Hulk Hogan, Kevin Nash and Roddy Piper, Sting and Randy Savage—always involved the top names. Did that take away from the Pay-Per-Views? I don’t think so.

My theory was, people would pay for the quality of the story, not the talent in the story. I wasn’t afraid to put Pay-Per-View–quality talent on free television—as long as we could provide a Pay-Per-View story the audience felt they

had

to see.

On the other side of that, I used a “hook and drag” strategy: we would take something from the Pay-Per-View and develop it on

Nitro

the following night. Instead of just wiping the slate clean and starting over from scratch after the story climaxed, we wanted to

“hook” them at the Pay-Per-View, and then “drag” them into the next arc, continuing the story. I didn’t want to feel as if I was starting over each and every month, because it was simply too much.

We couldn’t do this on every story, obviously. But the nWo storylines often lent themselves to this strategy.

There was more to the Pay-Per-Views than coming up with “big” stories. The shows had to

feel

different from what was on free TV.

And each Pay-Per-View needed a unique personality. We were also looking for ways to make them sponsorable, the way a major sport-ing event like a NASCAR race might be, so that we would increase the revenue stream.

Hogg Wild

at Sturgis was born from those considerations.

THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

223

Born to Be Wild

Sturgis

I’ve always been a biker at heart. When I was ten or so, I had a five-horsepower minibike I used to ride around the neighborhood. I bought my first motorcycle before I was old enough to drive, and I’ve owned at least one ever since.

Having grown up in the Midwest, I knew about Sturgis, the yearly motorcycle rally in Sturgis, South Dakota, which brings together hundreds of thousands of bikers from all over the country each August. I’d never gone—it was one of those situations where when I had the time I didn’t have the money, and vice versa. But I knew about it, had read about it, and had always wanted to go. The timing just never worked out.

When we increased the Pay-Per-View schedule in 1995 and began looking for new and different ways to give these new Pay-Per-Views an identity, it occurred to me that it would be really cool to put on an event at Sturgis. I knew that there would be anywhere from 400,000 to 750,000 bikers there. More importantly, I knew there was an attitude and a demographic that would really give that August Pay-Per-View its own personality.

Just as I did with Disney and Hulk Hogan, I wanted to co-brand WCW with the biker image. The perception of bikers was that they are pretty edgy, aggressive, beer-drinking, fistfighting kind of guys. I thought that was an attitude that would serve WCW well, given the direction we were going with

Nitro.

Sponsorships

I also saw Sturgis as a chance to connect with sponsors in a way wrestling had never done before. Sponsorship opportunities at certain levels seem obvious: there’s a halo effect that comes with an 224

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

activity that is associated with prestige. Rolex and golf, for example.

But it’s not so obvious on the opposite end of the spectrum, where wrestling—as well as motorcycles, for that matter—is concerned.

Advertisers looked at the sheer eyeballs associated with wrestling and recognized that it’s a powerful way of reaching a mass audience.

But they also looked at the audience—or what they

thought

was the audience—and didn’t want to have their product associated with it.

The way to overcome that in my mind was to change the perception of wrestling. Wrestling will never be golf, but if you look at the wrestling audience and the NASCAR audience, you see a very close relationship. NASCAR had a great deal of success with blue-collar advertisers. Their target audience wasn’t playing golf or wearing Rolexes, but they were making sixty or eighty thousand dollars a year, drinking beer, driving trucks, wearing Levis, and that sort of thing. That was our audience, too.

And that was the audience at Sturgis. Some people who hadn’t been there were afraid of it, because of what they’d heard about the motorcycle clubs. But that wasn’t really what it was all about. I’ve been to Sturgis now maybe ten times, and I’ve never seen so much as a fistfight. Despite the perception, the reality is, you have a bunch of middle-aged guys trying to relive a little bit of their youth.

I’m not saying that there isn’t a darker side of the event—and I’m sure law enforcement could point that out—but for the most part, it’s just like a state fair for guys who like motorcycles.

I realized that “motorcycle culture” was already part of the mainstream. People saw it as edgy, which made it attractive. This was a couple of years before

Monster Garage

and

American Chop-pers,

two wildly successful cable shows. I saw the motorcycle phenomenon coming before a lot of other people did. I wanted to be the first one to plant my television “flag” in Sturgis.

I realized it might take a few years before the sponsorship deals opened up. And from an economic point of view, Sturgis didn’t make a lot of sense, because we weren’t going to get a gate. We couldn’t charge for tickets. I also knew that, because of the very na-THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

225

ture of an outdoor event, our production costs would be much higher than normal. Travel was also going to be a problem, because Sturgis is in the middle of nowhere. Hotels book up two years in advance, and rental cars are nonexistent; there are a lot of things that make producing an event at Sturgis difficult. But I thought in the long run, if we were able to maintain our presence there, as an annual event, the money that we would not make in traditional ticket sales would be more than offset by attracting advertisers and sponsors in the long run.

Of course, there were critics, and the whole idea of doing a Pay-Per-View at Sturgis was questioned by people supposedly “in the know” who were writing in dirtsheets and on the Internet.

That didn’t bother me one bit. Anytime I did anything out of the box, the dirtsheets and some of the hard-core wrestling fans gave me flack. But I knew that none of these people had their heads inside the entertainment industry. The only thing they understood was what they had grown up with.

On the Road

The idea of the Pay-Per-View was an easy idea to sell to WCW, especially to a lot of the talent. Sting, Big Bubba Rogers, Diamond Dallas Page, the Steiner Brothers, Madusa—there were probably ten or twelve of us who all had Harleys and liked to ride.

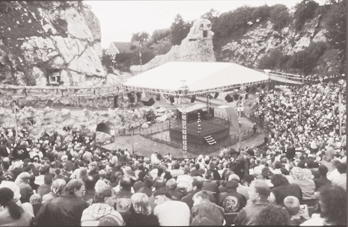

I couldn’t just show up with a ring and hope I could put on a wrestling event, so I went to the city of Sturgis, hoping to get support. I met with the city council and members of the rally committee responsible for putting on the event. They really rolled out the red carpet for us and made it easy to bring our monster of a production there. We arranged to construct an outdoor arena a block off Main Street.

Someone came up with the idea of shipping our bikes to the Mall of America, and then riding to the event. We’d film the ride across country, using it as part of the Pay-Per-View and for promotion.

226

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

And so we did. We had a press event at the mall, then jumped on our bikes and headed out. There were ten or twelve motorcycles, a couple of motor homes, a pickup, trailers, a truck with all sorts of miscellaneous parts in case someone broke down. We had crew members, mechanics, family—I brought my wife and my kids with me. It was a real adventure. The weather was hot and miserable, we got lost once or twice, and we ate a pound of bugs at eighty miles an hour. But at the end of the night we’d pull up at a hotel, meet at the bar, and just have a good time. It was quite the experience.

We came together in a way that you just don’t get in the course of your normal everyday business. A bond developed between Sting and me, the Stemers, Madusa, and the rest of the crew, thanks to this trip.

By the time we pulled into Sturgis, most of the outdoor arena was already set up. When I looked at it, I was really proud of what David Crockett and the rest of the crew had done.

---------------------------------

----------- ----------------

-----

-

Sturgis.

THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

227

The afternoon before the show, a tremendous storm struck. We got hail that was probably an inch or an inch and a half in diameter, forty- or fifty-mile-an-hour winds, and a torrential downpour of rain. I was standing there looking up at all the rigging for the lights, and I thought,

Oh my God, all of this is going to come crashing down

around me.

Fortunately, nothing came down.

Like the farmers say, if you don’t like the weather in South Dakota, stick around for twenty minutes and it’ll change. Sure enough, in twenty minutes, the storm was over. We went on to have a great show the next day.

There were no seats at ringside. We let anyone who wanted to ride their bikes right up to the ring. So we were surrounded by hundreds, if not thousands, of Harleys. When wrestlers were announced, guys revved their bikes, so you had this enormous roar as each event got under way. Pretty bad-ass.

Different, definitely different.

Dealing with Hogan

Not too long after Sturgis, Hogan and I were together in Denver when someone called him and said, “Hey, Vince McMahon is in town, and he’d like to talk with you.” Our contract with Hogan was coming up for renewal, and it was pretty obvious what McMahon wanted to talk about. Hogan looked at me and said, “I can’t believe it. Vince McMahon is here and wants to talk to me about a deal.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to go talk to him and hear what he has to say. But don’t worry; I’m not going to do a deal with this guy.” I wasn’t worried, but I was concerned. Hogan’s heel turn had made him especially valuable to us.

In my opinion, the nWo would never have been the nWo without Kevin Hall and Scott Nash. Their attitude and personae were unique to the wrestling business and fit the architecture of the con-228

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

cept as if it was meant to be. That said, without the Hogan turn and the impact that had, the overall chemistry and angle wouldn’t have lasted as long as it did.