Controversy Creates Cash (31 page)

Read Controversy Creates Cash Online

Authors: Eric Bischoff

I hate golf. And anyway, most times when you’re running or playing golf or whatever, you’re still thinking about your business.

But if you’re learning to fly, you can’t afford to think about anything else. You’ll likely die.

I’d always been fascinated by airplanes—and maybe subconsciously, a little scared. The Detroit metro airport was located not far from the cemetery where my grandfather was buried. Occasionally, on Sunday mornings my grandmother and I would get on a bus and go to visit his grave. Then she’d take me to watch the airplanes take off and land. That probably started my fascination with flying.

And from the time I was a teenager, I had recurring nightmares where I’d be in an airplane and something catastrophic would happen while I was on approach. I’d be hung up in power lines or run out of gas, or something else would make me crash. I looked at it as a challenge—the only way I’m ever going to overcome this fear or nightmare is to do it.

I became passionate about flying, and still am to this day. Learn-236

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

ing to fly, getting my pilot’s license, my own plane, and then my in -

strument rating, were very intense and very effective as a release.

The Next Phase

Merging Our Futures

The FCC approved Time Warner’s purchase of Turner Broadcasting in September 1996, roughly a year after it had first been announced.

WCW was a tiny part of a company that cost Time Warner an estimated $7.5 to $8 billion in stock.

The merger didn’t seem to affect me or WCW. Ted Turner still headed Turner Broadcasting, and the people I answered to remained the same. From my perspective, nothing had changed.

Or so it seemed.

I’d never been part of a corporate merger before, so I talked to someone early on about what to expect. He told me, Well, at first, you won’t notice it too much. Then, somewhere in that first year, you’ll notice that you’re getting new rules and procedures that will subtly change the way you do business. By the end of the second year, going into the third year, you won’t recognize the company you work for anymore.

Sure enough, by early 1997 people were telling me what I could and couldn’t do. They all had good excuses, but that had never happened before. All of a sudden there were legal considerations about what could air and restrictions on whom I could hire. In and of themselves, they seemed innocuous at the time. But eventually, they began to add up.

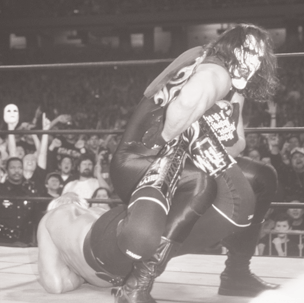

The Scary Sting

A lot of

Nitro

in 1997 was about Sting—even though he never wrestled.

A lot of our wrestlers didn’t like the nWo storyline. It was the THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

237

first time they had ever seen heels cleaning the arenas with the babyfaces. The wrestlers kept wondering when they were going to get their comeback. But seeing the way the angle was going and how the audiences were responding, I wasn’t anxious to let the babyfaces get their comeback too quickly. I wanted to milk it for as long as I could milk it. This was very disconcerting for a lot of the wrestlers who were used to a traditional formula.

On the other hand, once nWo started working, some of the non-nWo guys realized they needed to revamp their character. Sting was one of them. He’d been that highly animated character, with a plat-inum flattop, face paint, sequins, and all of that. He needed to up-date himself, get more of an edge. So we started exploring different options for that character.

Scott Hall came up with something he called “the scary Sting.” He wanted Sting’s character to have a little mystery about him, and danger. We never discussed it, but my guess is that Scott had seen the movie

The Crow

shortly before, because the connections between the lead character in the movie and what he suggested for Sting seem so obvious. They were both avengers, both mysterious, both out to right wrongs.

Sting embraced it. His character became an avenger, literally watching from the rafters, waiting for the right time to strike. The more the nWo succeeded in routing the WCW, the more he brooded.

An Evolution

Much like a lot of other things we had done that were not necessarily preplanned, we watched it evolve. Every week it became more and more apparent to me that we were onto something.

Every week that went by where Sting didn’t tell us what was on his mind, or why he was dressed in black—the more he didn’t tell us, the more powerful and interesting he became as a character. I just let it roll.

238

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

--------------------------------------

--------- ----------------------

-

-----

-

All too often then—and even more so now—we in the wrestling business don’t have the patience to let things build. We don’t have the luxury of time to let a story or character build. But I took the chance with this. Much as I did with the nWo, I let it grow without forcing it in any direction. After a few months, it became clear that this was something we could sustain. It was powerful enough that it was no longer a question of whether we could keep it going, but of how did we want to pay it off?

I decided I wanted to pay it off with a Hogan versus Sting. We’d never seen that match. Now it made perfect sense.

Hogan was an anti-WCW character. The old-line fans didn’t ap-THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

239

preciate Hogan as a babyface, and liked him even less as a heel.

Sting represented the last hope for the true, hard-core WCW fan.

By April or May of 1997, we’d decided to let it build toward

Starcade

in December. Then it became a question of keeping it fresh. That’s why we came up with things like Sting rappeling down from the rafters and showing up with a vulture. All those crazy things we did, from Sting masks on the wrestlers to fake Stings in the audience, came from asking ourselves how we could make it different.

We got a better reaction from Sting doing nothing than we had from most wrestlers wrestling each week.

On Top of the World, but

Not Quite Ready

Souled Out

Souled Out,

the Pay-Per-View devoted solely to nWo we aired in January 1997, was another attempt at giving a Pay-Per-View a different feel. At the same time, I hoped to explore and possibly lay the groundwork for separating WCW into two separate brands: the mainstream or older WCW brand and the rebel nWo.

By late 1996 or early 1997, I decided to try to create two separate wrestling brands, nWo and WCW. Each would have its own roster of wrestlers and, eventually, its own show. That way, I could have my own war. Everyone had always fantasized about an event pitting WWE and WCW wrestlers—a Super Bowl, if you will. That was never going to happen. But I thought that, by creating two brands, I would get as close as possible.

By now we were so far ahead of WWE that they were not even really competition, at least not in my mind. I was a little full of myself, to say the least, but there was nothing coming out of WWE

240

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

that led me to believe that they were going to be able to regroup at this point and challenge us.

And yet I knew competition was the key to our success. Us versus them was the formula that had gotten us to the top of the ratings.

First, it was

Nitro

versus

Raw.

Now it was WCW as seen by the true-blue WCW fan, and nWo. I decided I had to maintain the audience’s belief that nWo represented one style of wrestling, and WCW represented another. The clashes of those cultures and philosophies would sustain a tremendous story arc.

Because of that,

Souled Out

was designed to be the nWo’s version of what a Pay-Per-View should look like. Everything about it was designed to reflect the renegade, counterculture anarchy that defined nWo. It had a stark, industrial feel, and we tried to do things in keeping with that. Instead of coming to the arena in limousines, for example, we rode in on garbage trucks.

The interesting story there is that it was about twenty-five degrees below zero when we filmed the trip in. It was snowing, bitterly cold, but we wanted to shoot it at night in downtown Cedar Rapids, and the only chance we had was the Saturday before the Pay-Per-View. It was cold as shit. Brutal. But it did set the tone.

Then there was the beauty contest. Everybody else celebrates beautiful women. We wanted to celebrate—uh, not so beautiful women.

Sometimes on different college campuses around the country, guys will have contests to see who can bring home the ugliest chick.

And that’s where the idea came from. We wanted to find the nasti-est, gnarliest white trash we could possibly find. The women were in on it. We told them what we were doing. We said, “We’re looking for some real women, wink, wink.” A couple of them weighed two hundred and fifty, three hundred pounds.

As the leader of nWo, I was the one who got to pick the winner, crown her, and swap spit with her. At that moment, my wife sat back and said, “Oh, my God.”

The buy rate on the Pay-Per-View was only .47, a drop off from THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

241

December’s

Starcade,

which had hit .95. (The buy rate measures the percentage of possible cable subscribers who opt to pay for the program.) I won’t deny that I would have loved higher numbers.

On the other hand, I don’t think our expectations were all that high, and the lower number was not a tremendous disappointment.

This was the first time out for this Pay-Per-View, and anytime you’re launching a new show, you can’t expect the numbers to be stellar. The card—I forget the exact matches now—was okay, but it wasn’t of the caliber we had at

Starcade.

Even so, the numbers told me that we hadn’t built the nWo up yet to the point where it could sustain its own weekly show. I felt that as strong as the concept had been up to this point, we didn’t quite have the infrastructure in terms of story and talent to sustain it. And the buzz was starting to weaken.

Don’t get me wrong, the audience was still into it. We were still selling out arenas. We were still kicking ass on television. But we weren’t ready. I put off the idea of dividing WCW into two separate brands. The idea was good, but I had to slow the horse a little.

ECW & Paul Heyman

To hear Paul Heyman tell it, I was obsessed with his company, Extreme Championship Wrestling, around this time. According to some alleged histories of wrestling, both Vince McMahon and I took our best ideas from ECW. But the truth is, I didn’t pay much attention to ECW at all. I couldn’t even get it on cable where I lived.

ECW was a unique little company, with a nice little niche catering to so-called hard-core wrestling fans, but it was not the little niche that was interesting to me as a fan or, more importantly, one that had any sort of application to WCW.

I’m not sure what to say about Paul. He could be a chapter to himself. I first met him when he worked for Verne Gagne. Didn’t like him then; didn’t trust him then.

Creatively, I have a lot of respect for Paul. He’s got a very solid 242

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

and unique creative perspective. But he’s got serious integrity issues that I have a hard time overlooking.

Big Bad Eric

Trying to keep ECW afloat with very little money—it eventually went bankrupt—Paul needed to get his people to work under pretty ridiculous conditions. He needed people who were willing to go to the extreme to execute the vision he had for ECW. Most of all, Paul needed people who would show up to work when they weren’t getting paychecks.

One of the ways he did this was by painting a picture of how big bad Eric Bischoff and the almighty Ted Turner organization were doing everything they could to keep ECW down.

I didn’t give a flying fuck about Paul Heyman or ECW. Every once in a while, I’d get a call from someone who’d say, “Hey, I haven’t got a check from Paul Heyman in three months. He keeps telling me the check is in the mail, but it’s not. I need to work. Will you hire me?”

I’d take a look at the situation, and maybe I’d hire them. That’s all there ever was to it. Nothing sinister, nothing dark and evil. It was just business.

Paul would then turn the situation around. “There he is again, stealing our talent, trying to keep us down. They’re afraid of us.

We’ve got them on the run.”

Nothing was farther from the truth.

But the Internet community and dirtsheets hung on it.

We were doing 5s and 6s on TNT; he was doing .5s on what was then the Nashville Network. We were putting fifteen, twenty, twenty-five thousand people in arenas all over the country: he was putting eleven hundred idiots in a bingo hall. His Pay-Per-View drew nothing. There was no reason to believe that we were on the same playing field competitively. But it worked for Paul. Or at least, he thought it did.

THE REVOLUTION TAKES HOLD

243

I remember one wrestler who wanted to come to WCW. Paul couldn’t afford to pay him. The guy knew it. Paul knew it. Paul had some ridiculously loose contract that wouldn’t have held up in court. Knowing Paul, he may have written it himself after the guy told him he was leaving ECW; I’m not sure.