Controversy Creates Cash (12 page)

Read Controversy Creates Cash Online

Authors: Eric Bischoff

84

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

I didn’t come from the old NWA territory, and I certainly hadn’t been around long enough to “pay my dues.” I didn’t lace up the boots—I wasn’t a wrestler. I was a young upstart. Plus, I was part of a regime that replaced people who, whatever the realities inside the company, had long histories in the business.

All of that helped make me instantly unpopular with the dirtsheets and the Internet community, which was still in its infancy at the time. No matter what I did, no matter how positive the outcome, the reaction was negative.

As far as the wrestlers themselves went, I had different relationships with different guys. To a lot of the old-time guys, I was an outsider, not a wrestler, and they resented that. But I had good relationships with some veterans. One of them, at least at first, was Ric Flair.

Ric came back to WCW in 1993 while I was executive producer. I went over to Techwood, the original Turner office building in Atlanta, with the other WCW department heads for a kumbaya moment where everyone welcomed Ric back. I wasn’t part of the decision to bring Ric back; no one asked me for my opinion or input. But that was the beginning of my relationship with Ric—

shaking his hand and congratulating him.

Firing People

One of the big misconceptions that’s been created is that Eric Bischoff went around firing a lot of people as soon as he got a management job. Nothing is further from the truth. The truth is, I should have fired a lot of people, but I didn’t.

If you go back and look at the people who claim they were fired by Eric Bischoff, there are some holes there.

Jim Ross is a good example. I had no more influence in the decision to let Jim go than the receptionist did. The truth is, the company didn’t fire him—Jim decided he wanted out after the change in management.

RUNNING THE SHOW

85

-------------------------------------------

------ ---------------------------

----

----

--

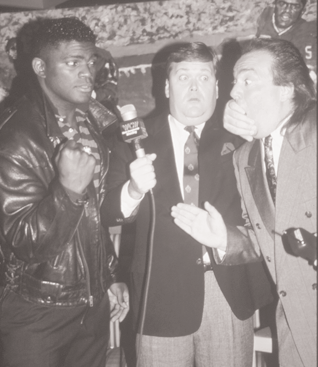

Jim Ross between Lawrence Taylor (L) and Paul Heyman.

Jim Ross

A lot of the changes that followed Bill Watts’s departure came about because of an internal audit by the international consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton, which had been reviewing WCW before Watts’s infamous racial remark. Besides all of the management and internal human resources problems—and there were

a lot

—the audit looked at the programs WCW was putting on.

86

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

Besides being WCW’s lead announcer, Jim was also vice president of wrestling operations. This meant Jim oversaw the production department, the announcers, and live event booking. He worked closely with Watts on talent issues and television booking.

In short, Jim was tied so closely to Watts that he got thrown out with the bathwater.

I want to make it clear: I didn’t like working for Jim Ross at the time. Jim Ross was—I won’t say a tyrant, but he was a miserable human being. A lot of that had to do with the fact that he reported to Bill Watts and had to take a lot of Watts’s shit. Jim had to support Bill Watts’s decisions, whether he agreed with them or not. He had to be his hatchet man. Jim took responsibility for a lot of what Bill Watts chose to do. It was a miserable position to be in.

One of things I respect about Jim Ross is that he’s an incredibly hardworking, loyal person. If the guy above him says, “This is what I want to do,” he goes and does it with one hundred percent effort.

With respect to Bill Watts, that put Jim in a very difficult position.

A Kick in the Balls

Bill Shaw moved Jim out of wrestling operations and put him into sales and syndication. Jim took that as a real kick in the balls. He looked at it as a demotion. Jim didn’t have to take a cut in pay, and there were no changes to his contract, but it must have been hard on his pride.

A few days later, I was appointed the new executive producer of WCW programming.

Jim took that as an even

bigger

kick in the balls. Here’s Eric Bischoff, a guy who’s barely been in the business long enough to have a cup of coffee, a guy who worked for him, probably three levels below him, now that I think about it, coming in and giving him orders.

Jim Ross, because he was so miserable, contacted Vince. It be-RUNNING THE SHOW

87

came obvious to Jim that McMahon would hire him. So Jim called Bill Shaw and asked if Bill would let him out of his contract.

At that point, I did get involved. Bill Shaw came to me and asked, Eric, what should we do? Should we just hold on to him and keep him away from Vince? Force him to work out his contract in sales?

I said—and not as any big favor to Jim, just as the right thing to do—

“Why keep a guy here when we’ve been surrounded by negativity

and bad morale and political infighting? Why would we want to keep a

guy here when he’s miserable? Let him move on with his life.”

I told Bill Shaw to let him out of his contract so he could go work where he wanted. That’s the real truth. I didn’t fire him at all.

I helped Jim get what he wanted.

Getting Himself Over

But Jim got himself over by claiming that I fired him, and that WCW was being run by a bunch of unqualified idiots. Jim would run around and say in his good-ol’-boy drawl, “I got fired because of that damn Eric Bischoff.”

I don’t know how Jim reconciled what had been going on under Bill Watts—a group of Cub Scouts would have done a better job running WCW than Watts had done. But criticizing me endeared him to a lot of people. People looked at me as this young kid who had come out of nowhere and was wielding

all

this power and abus-ing

all

these people who’d been in the business for so long and had contributed

soooo

much and had a legacy in the wrestling business yada yada yada. I was totally disrespecting them.

Right.

A lot of people got themselves over that way, and Jim Ross was one of the first.

Part of it was probably that he was hurting. And maybe he thought in his mind that I was pulling all the strings behind the scene, but I wasn’t.

88

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

Tangled Mess of Political BS

Before Bill Shaw there were no lines of communication between WCW and Turner execs. Things got filtered through various parties.

Take Jeff Carr. Jeff was, I think, the vice president of programming at TBS at the time. He was a real wrestling fan—almost too much of a wrestling fan. He thought more like a wrestling fan than a programming executive sometimes.

This cut both ways. Jeff was a big supporter of WCW many times when executives in CNN’s North Tower—where all the top brass worked—had questions or even suggestions about WCW.

Rather than walk across the atrium and come talk to us, they would talk to Jeff Carr because,

Well, Jeff Carr’s a wrestling fan and he

works at TBS, therefore he’s the best person to talk to.

Unfortunately this was problematic. Jeff might have been a wrestling fan, but he wasn’t running WCW and wasn’t familiar with what we needed or were trying to accomplish.

Another link—or maybe

supposed

link—to Ted Turner was a guy by the name of Jim Barnett. Jim was a longtime promoter who’d been part owner of Georgia Championship Wrestling and had a long history in Chicago dating to the early days of televised wrestling. He’d also had some experience working for Vince. He was recognized at Turner as a guy who knew the wrestling business.

Legend had it that Ted Turner relied on him quite a bit when he decided to buy WCW. It was a legend that Barnett propagated.

Rest his soul, but Jim was one of the most political people I’ve met in my life. He was a great old guy, and it was hard to dislike him, but he was a lot more of a politician than he was an expert on modern wrestling.

No one at WCW really knew how much Ted Turner talked to Jim, or even if he had relied on his advice when Ted decided to buy WCW. But I can assure you that Jim let everyone know that he had Ted Turner’s ear. And Jim Barnett played that for all it was worth.

RUNNING THE SHOW

89

Jim was essentially a consultant who was there to voice his opinion on anything that anyone needed an opinion on. He had an official title—I think when I was there, he was in charge of international—

but he was really there just to say what he thought of things.

Mind you, the franchises Barnett had been associated with had been sold or put out of business years before, left behind in the wake of Vince McMahon’s wrestling revolution. But to the executives at Turner, Jim was an invaluable resource.

It was laughable, but you have to put yourself in Turner Broadcasting’s shoes. The company didn’t have anyone they could rely on who was a seasoned wrestling executive, someone with a corporate memory, if you will. Jim Barnett had a lot of wrestling experience, he knew the players, and he knew the culture. That’s why he was there—so the Turner people could get their basic questions answered.

Straightening Things Out

As likable and well-intentioned as the Jeff Carr and Jim Barnetts of the world were, these informal and circuitous lines of communications hindered the organization. And there were plenty of other people who were neither as likable nor as well-intentioned toward WCW. Their agendas, at best, were personal, aimed at making themselves look good, no matter what the cost.

Bill Shaw, though, really engaged. He was one of the first executives from the North Tower who spent time in the WCW offices and made an attempt to learn firsthand what was going on. He developed his own opinions instead of depending on consultants and people who were supposed to be knowledgeable.

Bill attended meetings, spent time on the sales calls, went to arena shows, attended television tapings—he really got in and tried to understand the business. Once that happened, it minimized a lot of the communications problems. People in the North Tower 90

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

stopped making decisions that affected us based on things that had filtered through the tortuous lines of communication.

It soon became evident that anyone who needed to get to Ted would do so through Bill Shaw and no one else. This had a significant impact on the politics within WCW. All of a sudden, people at midlevel management no longer jockeyed for position. The politics and all the BS that went with it ended.

Righting the Ship

Hemorrhaging Money

In 1993, WCW was a $24 million company that was losing $10 million a year. There was a tremendous amount of pressure on all of us to turn that around.

The one thing we didn’t contemplate was laying anyone off. The cumulative effect of the Watts era had taken its toll, and Turner wasn’t anxious to go on a whole-scale firing spree. They wanted to figure out how to shore up the business instead of hacking and slashing staff.

We discussed what to do from all different perspectives. Although I wasn’t in charge of the other departments, I was happy to speak my mind.

Coming from Minnesota and being an outsider, I wasn’t really familiar with the history of WCW and the NWA. I didn’t know much about the old promotions’ legacies, which everyone else thought were so important. In my mind, if they

really

were important, the company wouldn’t have had financial problems to begin with. Maybe in retrospect I should not have disregarded the history and traditions of the NWA/WCW quite as much as I did.

What I was most concerned with was giving our company a national rather than regional feel. We were competing for national ad-RUNNING THE SHOW

91

vertisers, the M&M Mars Candies of the world, the toy manufacturers and big retailers. Focusing on regional personalities and histories didn’t ring my bell. I didn’t think that would help convince advertisers and audiences that WCW was a legitimate alternative to World Wrestling Federation.

Heresy

Bob Dhue and I started butting heads early. Some of the things Bob wanted to do made absolutely no sense. For example, his solution to increase revenues in the live events side of the business was to produce more shows. So instead of doing, say, one hundred and fifty shows a year, he wanted to do two hundred and fifty.

Well, the problem with that is, it doesn’t scale properly. If you’re losing money every time you go out the door, why would you want to step out the door another hundred times? Until the perception of the product changed, increasing the live event schedule would only increase our losses.

My position was, let’s just cut live events all together. Let’s go out the door twenty-four times a year or whatever we need to make television and Pay-Per-Views, and that’s it. While we wouldn’t be making any money from live events, we’d be losing less. A

lot

less.

That was completely contrary to everything everyone “knew” about the wrestling business. It was as about heretical as you could get. Back in the old days of the territories, the associations kept the guys on the road every week. That’s how wrestling was supposed to work. The focus was on live events.