Controversy Creates Cash (23 page)

Read Controversy Creates Cash Online

Authors: Eric Bischoff

172

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

looked like a wino sleeping on a park bench. I said to myself,

This is

insane. This guy is running around, badmouthing Hogan, badmouthing

the company, and walking around like one big dark cloud. I’m paying

an entire production crew to suck air because this idiot is taking a nap

in the middle of the day.

It dawned me that I no longer wanted to do business with Jesse Ventura. The fact that all he did was bitch and moan when I woke

---------------

him up confirmed it.

-------------

------------

------------

------ ---------------

-------

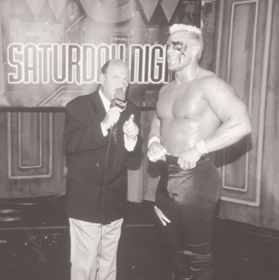

That’s Steve Austin on the far left, not yet stone cold.

PRIME TIME

173

I didn’t fire him, because he had a contract. I just quit using him and let his contract run out. I thought he was cancer.

Stone Cold Gone

Steve Austin was another guy I fired roughly around the same time.

The truth is, the best thing I ever did for Steve Austin was to fire him—though I assure you, my idea at the time wasn’t to set him on the road to becoming a megastar.

Steve went through a lot, mentally and physically, during that time, and he came out of it—well, you know where he came out: he became one of the most famous wrestlers of all time. That says a lot about him as a performer, and even more about him as a man. My firing him—no matter whether I was justified or not—added a lot of fuel to an already competitive guy, but what he achieved was completely his own.

A lot of ink has been spilled over what happened—all of it wrong, at least from my perspective. Here’s the real story.

Steve wasn’t Stone Cold Steve Austin then. He hadn’t developed or probably even thought of that character. But he was a pretty important wrestler in the WCW universe before Hogan came in. He’d been a tag team partner with the late Brian Pillman, and wrestled solo as “Stunning” Steve Austin, taking WCW’s U.S.

title in 1993.

When the word first broke that Hogan was coming to WCW, Steve came to me with a storyline that he wanted to work with Hogan. I don’t recall the details now, but I do remember it had something to do with Steve being some kind of relative of Hogan’s—Steve had a little bit of the Hogan hairline at the time.

There was enough meat on the bone that I thought we could work with it. But I also knew that Hogan wanted his first program to be with Ric Flair. So despite the quality of the idea, there was no way it would work at that point.

I didn’t handle the situation as well as I could have. I should 174

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

have said to him, “Hey, Steve, here’s what’s really going on. I like your idea, and maybe we can work on it in the fall or early next year. Let’s keep it in the hopper, and in the meantime, here’s where we’re going and why.”

Had I done that, Steve might have had a better attitude. But I didn’t. I just said something like, “Sure, let me think about it,” or something to that effect, and let it go at that. Knowing Steve the way I know him now, he probably took that as a slap in the face.

Just like Jesse, Steve drifted into the bad-attitude category. Add to that some personal issues and injuries, and you have a guy walking around with a kind of pissed-off taste in his mouth.

Steve’s contract was coming due, and we were negotiating a new one. I think he was making about two hundred or three hundred grand a year at the time. At that point, I wanted to keep Steve on the roster, despite the fact that he was out of action because of an injury.

“I’m Not Home”

Steve lived in Atlanta. Even though he was out with an injury, we wanted him to come in for an interview we were filming at Center Stage in Atlanta. He didn’t show.

Given that there was some disorganization in the WCW at the time, it may have been that he didn’t know he was scheduled for an interview, though I don’t believe that was the case. In any event, I asked Tony Schiavone to give him a call and have him come in so we could do the interview. The idea was to keep the character alive on TV, even though he was out with an injury.

Tony came back and told me that he had talked to Steve’s wife, who said he wasn’t around.

Which would have been okay, except that Tony told me he heard Steve yelling in the background, “Tell that son of a bitch I’m not home, and you don’t know where I am.” When I heard that, in my mind, Steve was gone. That just wasn’t PRIME TIME

175

acceptable. When I got back to the office the next day, I said,

“Okay, send him a letter—we’re done with him.”

I’ve been criticized for not firing Steve in person. Certainly Steve made an issue of it later. But given what Tony had told me, I didn’t feel like I owed him any other type of response. Steve and I have since spoken about this. I have to admit, the way I handled it wasn’t great, though given the same situation I would probably react the same way.

Within months of leaving us in the fall of 1995, Steve wrestled for Extreme Championship Wrestling, better known as ECW. He went from there to WWE, where he evolved into the Stone Cold Steve Austin character. You know the rest.

Of course, given what happened later, leaving the WCW was a blessing in disguise. Steve wouldn’t have been able to become that rattlesnake character in WCW at the time. We had too many guys in front of him. But when he went over to WWE, there wasn’t a lot of talent he had to rise above. Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good—and in Steve’s case, he was lucky

and

good. He was lucky to be in a company that needed him at the right time. He didn’t have to overcome a lot of politics and bs to prove that he was capable of doing what he could do.

Controversy & Trucks

900 Gossip

In the early and mid-1990s, WCW and WWE used 900 lines as a way of adding revenue and generating interest for the product. Fans would call up the numbers, paying by the minute for inside information that wasn’t available elsewhere. This was before the Internet was really popular, remember, and the lines—some of them independent—were a source of supposed inside information.

176

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

-------------------------------------------

---------- -----------------------

-----

-

“Mean” Gene and Sting.

They were also a source of controversy. In order for the 900

lines to be successful, they had to piss people off. So they were in-herently a problem.

One of the 900-number deals we struck was with Gene Okerlund, the well-known wrestling announcer who’d come over to WCW. The deal let him share in the profits from the line. This meant that he had a self-serving reason to be controversial.

Overall, I didn’t have too big a problem with that, but the talent often did. And sometimes we were criticized by people outside the industry.At one point in 1995 Phil Mushnick wrote a column in the

New

PRIME TIME

177

York Post

ripping Gene—and us—for plugging a story on the death of Jerry Blackwell with a tease along the lines of:

What famous wrestler just

died?

When you called up, you had to listen until the end of the taped message, staying on the line for several minutes, before hearing the details. We drew a fair amount of complaints on that one.

I don’t remember any of the incidents specifically, but there were times when the line threatened to get out of hand. I’ve always had a great relationship with Gene, but nonetheless, you give Gene enough rope and he’ll hang you with it. Wrestlers and the crazy shit they do gave Gene a lot of material. Add to that the “scoops” he was able to create by, if not fabricating them, blowing things out of proportion—well, he rubbed a lot of people the wrong way.

But, at ninety-nine cents or a dollar-fifty a minute, the line and others like it were a great source of cash. And there were so many other things going on that were more important, it was hard to be sensitive to it—even though I fell victim to it myself from time to time.

It was uncomfortable, but at the end of the month I looked at how much money WCW made.

Okay. So I’m a little pissed off. Who cares?

Monster Trucks

Sometimes when you try things that were never done before, you find out why—they’re bad ideas. But I was willing to take that chance.

In our quest to do something different, we hooked up with a monster truck company in 1995. We integrated monster trucks into several skits and shows, including

Halloween Havoc 1995

where we drove—or appeared to drive—a monster truck off a five-story building.

That’s

very

different. But the monster truck–wrestling connection didn’t work.

The monster truck idea was part of a product integration strategy aimed at launching a licensing platform. The opportunity, when we were approached with it, made a tremendous amount of sense.

But I made the mistake of proceeding with the idea before I had a definitive deal signed, sealed, and delivered. As I committed to the

178

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

-------------------------------

---------- ---------------

-----

-

idea, the people I was doing business with became more aggressive in pursuing their terms—they wanted too much from us. So much so that I lost interest pursuing it. The deal was no longer fair.

I learned a little about negotiating and leverage from that. I had taken the people I’d started negotiating with at face value from the beginning, and that was a mistake. They turned out not to be as fair as I thought.

To use a poker analogy—you just don’t commit to the pot without knowing that you have a good hand. I’ll never do that again.

Or at least, I’ll try not to.

Wrestling with Peace

Ironies

Creating

Nitro

was such a major event that it tended to overshadow everything else that WCW did in 1995. But looking back, there were a lot of remarkable things that happened that year. One was our trip to North Korea.

PRIME TIME

179

The wrestling matches that we took part in were aired during the summer of 1995, right before

Nitro

went on the air. But we actually went to Korea in April. While the visit didn’t make much of an impact on WCW, I can still recall it vividly. It was like visiting the far side of the moon.

By early 1995, we had rebuilt our relationship with New Japan.

Antonio Inoki, a former Japanese senator and then chairman of the company, called me and asked for some help contacting Muhammad Ali, whom he had fought in a boxing-versus-wrestling fight in the 1970s. Ali had been recently part of a WCW event, and I was able to get them in touch.

Antonio Inoki is an interesting guy and a bit of an enigma. A successful politician, he served in the Japanese House of Council, which is similar to our senate. But he became involved in a scandal that killed his political career, forcing him to resign from his party leadership post.

He’d been a wrestler before going into politics, and in the mid-1990s he turned to wrestling to resurrect his political career. Inoki proposed to bring Japanese wrestlers to Pyongyang, North Korea’s capital, as part of a peace festival.

Let’s wrap ourselves up in the irony of that for a second:

Wrestling.

World peace.

Okay?

Actually, the idea was not quite as ironic or far-fetched as it sounds. Japan and Korea have always had extremely strained relations, going back just about to the beginning of time, when they would take turns pillaging each other’s country. Things had been especially bad with North Korea ever since the beginning of the Cold War. Just as other sports have sometimes been used to thaw relations between different countries, Inoki hoped that wrestling could help bring the two old enemies together.

And if it worked for Japan and North Korea, he thought, why not add a few American wrestlers to the mix?

180

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

A Love for Travel

When I got the phone call and I was asked if we’d be interested in bringing some of our guys to North Korea, I have to tell you that, on a personal level, I was excited.