Controversy Creates Cash (18 page)

Read Controversy Creates Cash Online

Authors: Eric Bischoff

HULK HOGAN

133

----------------------------------------

------ -----------------------

--------

- --

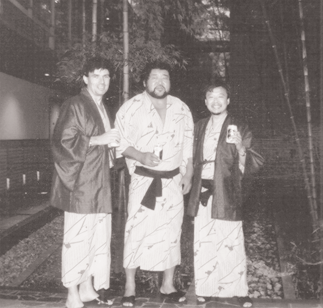

Me, Masa Saito, and Sonny Onoo at a traditional bathhouse.

The major Japanese promotions, All Japan and New Japan, drew fifty or sixty thousand people to their shows. Doing business with them gave us a way to offset our talent budget, which at the time was probably around $15 million. By subcontracting a group of performers for a high fee—“lending” them to the Japanese companies—we offset that cost significantly.

There were other benefits. Sending our wrestlers to Japan and elsewhere gave us an international reputation. Bringing their wrestlers to America—usually part of the exchange deals—did the same.

While WCW had done some business with Japan in the past, I wanted to expand that. I also wanted to mend some fences, since 134

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

there had been disputes between our company and the New Japan promotion prior to my taking over.

It happened that the main American talent liaison with New Japan was an old friend of mine from high school, Brad Rheingans.

Back in our younger days, Brad was a wrestler, and a damn good one—he made the U.S. Olympic team, though unfortunately for him it was the year we boycotted. Brad helped me smooth over past problems, and WCW was able to develop a very strong relationship with New Japan Pro Wrestling.

A Visit to Japan

When I set up a meeting with the New Japan promoters in early 1994, I hired Sonny Onoo—who’d invented and sold Ninja-Star Wars with me years before—as an interpreter and informal business and culture consultant. Sonny grew up in Japan and understood the business culture there. I knew that doing business in Japan for an American is quite extraordinary because of the differences in how we do business. He helped me really understand the Japanese mind-set and negotiating process.

It was also enjoyable to go to Japan. You can go to Europe, South America, even parts of the Middle East, and it will feel somewhat familiar. But when you go to Japan, you can’t even read the traffic signs. You don’t have the slightest clue what people are saying.

The arena shows were inspiring. Sixty or seventy thousand people were watching wrestling. At the time, we were lucky if we could draw eight or ten thousand. I began studying and thinking about what was going on around me, trying to find elements I could bring back to WCW.

In Japan, a big dome show would typically receive major coverage in the sports pages and other media. Wrestling was treated like a legitimate sport, unlike here in the United States. Could you imagine seeing front-page coverage of a WCW or WWE Pay-Per-View in the

New

York Times

or

USA Today?

That sort of thing was routine in Japan.

HULK HOGAN

135

There was no way I could change that. That train left the station a long time before I got there.

The Japanese audiences also believed that the things happening in the ring were real. I couldn’t change that back in the United States either—there was no way I could take audiences back to 1940 or 1950. But there was a psychology to the Japanese style that

could

be brought back and applied to our creative formula. Americans might not be willing to believe that everything about the match was real, but there might be a point where they were willing to suspend their disbelief—much as they would when going to see a play or movie and got caught up in the moment. If they were

allowed

to believe,

just for a moment or two,

they would enjoy the show more completely. And that would be the key to success.

Between Fact and Fiction

I realized then that pro wrestling needed to find a balance between showbiz and mystery—between the over-the-top entertainment that I believed in, and purely athletic contests where the ending does not appear to be predetermined. I wanted to find that sweet spot, where the audience believed—or at least responded as if they believed—that what they were seeing was real. Not the match necessarily, but the situation surrounding it.

I couldn’t articulate it at the time, but I was thinking about trying to find a way to heighten people’s suspension of disbelief. I needed to find a way to make what happened in the ring seem more believable, in terms of emotions if not facts. Suspension of disbelief had been ignored for so long in lieu of the other elements that go into pro wrestling that it was the one thing we could work on to heighten people’s interest.

I knew we could never make the audience believe wrestling was real, but I knew we could do things that would make the audience go,

Wow. I know all that other stuff isn’t real, but this, this must

be real.

136

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

If we could do

one

thing in the course of a two-hour broadcast that people thought was real, even if it was only for a moment, that made them suspend their disbelief, consciously or subconsciously, we would be more successful.

I started asking a lot of questions and watching the way the Japanese did it. I knew full well I couldn’t import Japanese style. I was thinking more about attitude and philosophy. That could be imported to the United States.

On the Air

The Best Option

Even though I tried to cut back on my on-the-air appearances as my executive role increased, I soon found myself spending even more time than ever in front of the cameras. Quite frankly, I was the best option we had. Not that I thought I was that good—just the best option under the circumstances.

I became the play-by-play guy for the WCW Saturday-night show because I knew more about where we wanted to go and what we wanted to achieve storyline-wise than anybody else. It was easy for me to sell the direction of the match.

Everything I did, I did to change the perception of the brand.

That required changing what people saw and heard on television, including the announcers. But my options were pretty limited. Our main announcer at that point was Tony Schiavone. Honestly, I wasn’t that comfortable with Tony Schiavone because he was associated with the regional stigma we were trying to escape. He also had a radio face. That wasn’t the image we were trying to project.

There really wasn’t anybody available outside the company either. Wrestling play-by-play guys don’t get nearly the credit that they should. It’s a difficult art form. You have to operate under tremendous stress and pressure, and there just aren’t that many HULK HOGAN

137

people available to do the job. It’s not like basketball or football or NASCAR where there are a lot of good announcers.

But Tony

was

a great play-by-play guy, which was why he stayed on air. He also happened to be one of the better producers I’ve ever worked with. Viewers saw him only as a personality, but he was working his butt off behind the camera. He was a detail-oriented person, calm under pressure, thorough and dependable. He had a work ethic second to none.

And by the way, he was a better play-by-play guy than I was. I just didn’t have the baggage he did.

I didn’t think of myself as a character. I would never have imagined that I was. If someone would have told me in 1994 what I was about to do in 1995, I would have laughed in their face.

Hogan vs. Flair

Hogan versus Flair was our focus in 1994. Their matches headlined our Pay-Per-Views, and remain among the most talked-about contests in wrestling history.

The first Hulk Hogan/Ric Flair Pay-Per-View in July 1994 at

Bash at the Beach

went well. A lot of that had to do with Ric Flair.

Ric was very gracious when it came to the creative side of things.

He did everything in his power to make Hogan feel comfortable.

There was nothing selfish or self-serving about Flair’s approach.

Flair won the second showdown at a

Clash of the Champions

special we did that August in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. But he didn’t get the title because he won without a pin or submission, upping the stakes for their Pay-Per-View that fall at

Halloween Havoc.

That bothered Ric a lot. I think he hoped to get the title with a clean win. He probably believed that since he did the job for Hogan in July, putting him over and establishing him, there should have been an automatic quid pro quo to return the favor. But I don’t think that any of us seriously considered taking the title off Hogan that quickly.

138

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

It goes against any kind of long-term planning and logic to flip belts back and forth. You bring in Hulk Hogan, create all this hoopla, use him to get a lot of media attention, position him to be the guy who is going to move your brand forward, and then beat him sixty days after he gets there?

No.

Long-Term Thinking

That was one of the problems that I had with the short-term, month-to-month booking mentality, even when Ric had the book.

People didn’t think long-term. No one, except myself, Hulk Hogan, Bill Shaw, and probably Ted Turner, understood what it meant to have Hulk Hogan as our franchise player.

Ric looked at it from a performer’s point of view—hey, I did the favor for you, you do it for me, and we’ll have a rubber match, best two out of three.

The time between the August and October Pay-Per-Views saw my relationship with Ric Flair begin to spiral downward. Flair and Hogan’s relationship also took a hit. The suggestion that Ric “retire” was partly to blame, even though everyone knew he wasn’t really going to retire.

We had to figure out some way of increasing the stakes for the

Halloween Havoc

Pay-Per-View. One of the obvious elements that we could integrate into the story was the premise that if Ric Flair lost, he had to retire.

Let me say it again: Ric wasn’t going to

really

retire. I don’t recall specifically, but I probably suggested he go away for a while, take some time off, and take advantage of the “absence makes the heart grow fonder” factor. When you’ve played your character out for a long time, sometimes the smartest thing you can do for a character is to take it off television and bring it back three months later when it feels fresh again. But Ric didn’t want to do it, and it became one of the more difficult scenarios that I had to manage.

HULK HOGAN

139

Flair’s Holdup

One of the things that made the angle more believable was the fact that Ric was in his mid-forties, which for most normal performers is knocking on retirement’s door. Ric had his insecurities about that, which was only natural. Add to those the insecurities that he had relating to Hogan—the fact that Hogan came in and became the franchise player, to a degree displacing Flair as the franchise player—and you can understand how Ric became extremely insecure about his position.

I think Ric initially looked at bringing Hulk Hogan in as a big opportunity for himself and the company. Hogan made Ric’s job as a booker easier. As a performer, if Ric was able to have matches with Hogan—even if he didn’t win—he would benefit. But the rub came when Hogan wasn’t interested in returning the favor by giving Flair the win in their next match. That’s when Ric realized this was all about Hulk Hogan, and Ric Flair was a secondary talent. That was hard on Ric’s ego. And that’s understandable.

I don’t think Ric thought that we were going to make him really retire. But he used the situation to negotiate a long-term contract for himself, using the

Halloween Havoc

match to, in effect, hold us up.

New Contract or No Match

Ric wanted a long-term deal. He agreed to go in the direction we wanted to go, provided we went in the direction

he

wanted. Which meant a multiyear extension.

Before

the Hogan match, before his contract was due.

Ric wasn’t necessarily interested in leveraging the situation for money. He was never really greedy when it came to money. I think he saw the situation as a way to get security, and that’s what he wanted.

However, the way he went about it made me lose some respect for Ric. I understand holding out to maximize your leverage, but I personally would never do that myself. He played it to the hilt, right 140

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

up to the very last minute. Even after we verbally agreed to terms, Bill Shaw actually had to bring a contract with him from Atlanta so Ric could sign it and could go on with the show.

Your Job Is to Perform

I come from a point of view where, if I’m an employee or an independent contractor and I take your money in exchange for my services, unless there is something written into that contract that gives me the ability to dictate how-where-when you’re going to use my services, then my job is to show up and do what you ask me to do. I always had a problem with wrestlers who felt they should be able to take my money and then force a situation where I had to engage them in a conversation about how and when and why I wanted to use them.

That’s not to say that I don’t want to share ideas or exchange concepts or improve a scenario, but at the end of the day, the job of a performer is to perform. Decisions about using the performer are made by the person writing the check.