Controversy Creates Cash (39 page)

Read Controversy Creates Cash Online

Authors: Eric Bischoff

Wrestling isn’t a science. When you send a wrestler out and say,

“Okay, you have ten minutes to get your match in,” sometimes they get it to within thirty seconds. Sometimes they go five minutes over.

At a Pay-Per-View where there’s eight or nine matches, if four or five go significantly over, you end up going into your main event short of time.

The main event is the reason that most people buy the Pay-Per-View, and it’s usually supposed to go twenty or twenty-five minutes. So you’re faced with a tough situation. If the match ends when it’s supposed to end—say after only seven minutes—it leaves a very bad taste in the mouths of the consumers. On the other hand, if you go over, you run the very real risk of losing your satellite time. Unless you’ve made prior arrangements, you go off the bird when your time is up.

I don’t remember exactly what happened at

Halloween Havoc,

300

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

but I assume that the earlier matches ran over significantly. At some point, we realized we had a problem, and we scrambled. We got hold of the Pay-Per-View companies and explained what was going on, asking for more satellite time. For the most part, we were given reason to believe that we had the additional time.

The Pay-Per-View industry wasn’t as sophisticated back then as it is now. For whatever reason, while some of our customers ended up getting the signal, the majority did not. Most of the people who had bought the Pay-Per-View never saw the finish.

Bad Choices

We had basically two choices.

One was to find a way to use the fact that the show was blacked out in a storyline. That was a very, very bad choice, because we’d be basically taking our customers’ money, not delivering what we promised, and then telling them that we did it on purpose for a storyline.

Bad to worse situation. Not an option.

The other choice was to replay the finish on

Nitro.

This way everybody who bought the Pay-Per-View could see it.

When that was presented to me as an option, I thought,

Well, at

least everyone gets what they paid for.

It seemed to be the most reasonable thing to do. I made the decision—or I should say, I recommended to the Turner committee running things above me—to run the finish on

Nitro,

and we did.

The problem with that—and frankly, I didn’t anticipate it—was that not only did the people who bought the Pay-Per-View see the ending, everyone who

didn’t

buy the Pay-Per-View saw it as well.

Those who paid their $29.95 or whatever said, “Hey, why should we pay for it when everyone else is getting it for free?” The argument wasn’t entirely valid, because the Pay-Per-View included a lot more than that final match. But disgruntled viewers made their point in a mass letter-writing campaign, e-mails, and phone calls.

UNRAVELING

301

Unfortunately, there was no way to put the ending back out there just for them. Refunding the money wasn’t an option either.

Typically, 60 percent of the Pay-Per-View fee went to the provider.

WCW got only 40 percent. If we were forced to refund the fee, we’d be giving back more than twice what we’d received. It was a

big

number.

The collective committees that ran WCW at the time went,

“What a disaster.” It reinforced their desire to get rid of WCW, and helped strengthen the various committees’ stranglehold over us.

The Pay-Per-View was my responsibility, and running over was my mistake. But did we do the best we could do under the circumstances? Absolutely.

The match had a 10.2 share during that quarter hour of

Nitro,

a tremendous rating, but no one cracked champagne over that one.

Out of the Tower

Among other mistakes that affected WCW that year was the relocation of WCW’s headquarters away from the CNN Towers and the rest of Turner Broadcasting. But it was a mistake that I, and everyone else at WCW, had no part in.

When Turner acquired the new NHL franchise for the Thrash-ers, space had to be found for the team’s headquarters. Harvey Schiller, who was on the fifteenth floor, wanted it close to him. The organization was kind of a crown jewel for Harvey. The only option was to move it to the floor below him—where we were.

We were told to find office space outside the CNN Center.

That kind of thing ordinarily doesn’t bother me. I can work out of the back of my car as long as I have all the tools I need. But I think a lot of people felt it was a slap in the face. Employees who had survived the redheaded-stepchild era, who’d been embarrassed just to walk through the CNN Center with a WCW ID badge, felt it was a real insult. They’d lived through the bad times and could be openly proud of their association with a division that was making 302

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

money and generating positive press from the likes of the

Wall

Street Journal.

Now they were rewarded by being told they weren’t important enough to be in the building.

Morale took another nosedive.

In retrospect, moving furthered the idea that we didn’t belong in Turner Broadcasting. When you lose direct communication with your peers and no longer have easy access to them, they consciously or subconsciously perceive you to be less than them. It has a variety of impacts.

Add to that, the place we moved to was a cesspool. It was a former factory and warehouse in one of the worst parts of town—

which says a lot, because there are a lot of worst parts of town in Atlanta. There were no windows, and the carpet smelled like mold.

We made the best of it. We cleaned it up and painted the walls, but it was not the kind of place where you showed up for work every morning and said, “Oh, man, am I glad to be a part of this.” You’d say, “Man, this place still smells like sewage.”

Angles

If Jesse Can Do It

Having lived in Minnesota as long as I did, I found it odd that Jesse Ventura, who’s kind of an outspoken, apolitical figure in every sense, could somehow get elected there. I think a lot of it was mostly his timing. The political dysfunction of Minnesota coincided with the popularity of professional wrestling, and he happened to be the right guy in the right place at the right time. Our success turned Jesse into a cult hero among a large part of the voting population of Minnesota. Jesse was smart enough to figure out a way to tap into that and exploit it while people who were more focused on traditional voting blocs had neutralized themselves.

Shortly after the election in November 1998, Hulk Hogan de-UNRAVELING

303

clared he was going to run for president. It was fun to laugh about, but it was so transparent and unoriginal that it didn’t have any legs.

We dropped it after a few weeks of laughs.

Burying the Hatchet in My Head

The conflict between the WCW and Ric Flair ended in the fall of 1998 with an agreement that brought Ric back to work. As soon as we settled things, we wove the conflict into a storyline arc, generating heat between Flair and myself.

It was natural. Ric Flair was still regarded as the traditional NWA/WCW guy. Viewers saw me as anything but.

Ric had spun the story to make me look like an evil villain and a power-hungry zealot. I was more than happy to take advantage of that. It fit the formula and made a lot of sense. Once we got business out of the way, we were happy to use it to benefit the company. We shook hands, drank a beer, and it was like we had never had a problem.

The storyline built until, at the end of the year, I met Ric for a match for control of the WCW. Ric’s son Reid got involved in the story. He was very young at the time, but he was a really cool kid—

still is. I think he was fourteen at the time, or maybe even younger.

Ric had started him as an amateur wrestler, and he was a big kid for his age.

I got a big kick out of working with him. He’d heard Ric spout off about me, but he didn’t let that bother him, or if he did, it didn’t show. He was polite and a hard worker. It was fun watching him get into the ring for the first time, with ten or fifteen thousand people cheering him on. I think I let him take me down and run me around the ring a little bit. He got a big kick out of it, and I got a big kick out of it.

We had to give the audience something more than just Ric kicking my ass to make the showdown feel special. So after he whipped me, Ric shaved my head.

304

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

I think everyone in the audience would have loved to have been wielding the blade. They were living vicariously through Flair, humiliating me.

As if being shorn wasn’t bad enough, we made a big deal out of my silver roots. I’d started turning gray when I was twenty-five, and by 1989 I was probably eighty-five percent silver. But I’d been dying my hair since 1985, and no one had ever seen me silver on camera.

Preparing for the match, I’d let the roots grow up a quarter of an inch, and when Ric shaved me I literally looked like Pepe Lepew, the Warner Brothers skunk.

Nash and the Book

I think Kevin Nash might have been the one who came up with the storyline. By that point, I’d given him the book. I was pulling back as far as I could creatively.

I’d lost my passion. I was so disillusioned and bitter and betrayed about everything that I didn’t have the desire to wrap my head around stories. In all the pressure of the situation, I couldn’t think of anything that excited me. I knew that meant I couldn’t come up with anything that would excite the audience either. We needed a fresh mind.

Kevin stepped up. He’d always been pretty creative, and he was the best person we had internally for the job. But he wasn’t a booker. With all the strong points he had, he remained a performer first, and thought like one. He also had to work under all of the ridiculous restrictions handed down from above, which made his job even harder.

People criticized Kevin for using the position to get himself over.

I don’t agree with that at all. If a performer is also functioning as the head writer, and the head writer knows that he needs to find a performer whom he can trust for a difficult part, who will he go to first?

UNRAVELING

305

Himself.

It’s unfortunate, but natural. I think Kevin wanted to be a success. There was a lot of discord in WCW at the time, and he knew that if he used himself in a difficult situation, he’d show up and give it one hundred percent, without bitching. That goes a long way when you’re working under that kind of pressure.

Asses in the Seats

The Turning Point That Wasn’t

Since the demise of WCW, people have tried singling out one or two things as the reason that WCW ultimately went under. They look for a simple turning point in the road to disaster.

Just about everything we were allowed to do at the time didn’t work, so it’s pretty easy to go back and look at certain things and form a revisionist point of view that says, See? If they hadn’t done that, this wouldn’t have happened.

One of the most popular—if that’s the right word—of these pseudo turning points is the incident on the January 4

Nitro

when Schiavone told the audience that Mick Foley was about to win the championship on

Raw.

The show had been taped a week before, so we knew what was going to happen.

Giving WWE endings away was something we’d done from the very beginning, though the dirtsheet writers seemed to have forgotten that at the time. They thought it was new, and a sudden fit of pique on my part. There were stories that I was angry with WWE

about some slight, imagined or otherwise. I wasn’t.

People did switch from our program to theirs, at least according to the Nielsen ratings. I don’t think it really mattered a bit. By that point, the tide had turned so significantly that us talking about one match didn’t matter.

306

CONTROVERSY CREATES CASH

-----------------------------

----

----

------ ------------------

-----

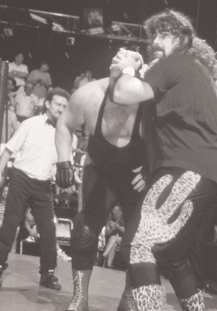

Foley, while at WCW. He’s wrestling as Cactus Jack in ’94.

Mick Foley

Mick Foley and I have a good relationship. At least, I think we do.

Mick may have a different opinion. He came up to me one day after one of his books was published, “Oh, man, I really apologize. I hope you didn’t take anything I wrote personally.” I said, “Mick, I didn’t take it personally because I didn’t read it.” I still haven’t. Probably should. But to my recollection—and granted, it’s been ten or fifteen years ago now—my relationship with Mick Foley was never bad. I liked him, and his family. He has a beautiful wife and what has always seemed to me to be a great relationship with her.

UNRAVELING

307

The biggest issue that Mick and I had when he was in WCW

was his propensity to do things that were dangerous to himself. He felt he needed to do these insane, high-risk stunts in order to advance his character and get to the level he wanted.

When I heard that his ear was ripped off in a ring accident in Europe, I wasn’t surprised. I was disappointed for him. Sorry it had happened. But not surprised.