Alphabetical (17 page)

Authors: Michael Rosen

For hundreds of years, non-Greeks have used the individual letters. At university, my essays were marked with the first four, just as people themselves are categorized in Aldous Huxley's

Brave New World

. The Phi Beta Kappa Society has been celebrating excellence in liberal arts and sciences in the US since 1779. You can't talk about the volume of circles without âpi', we have âalpha males', âgamma rays', âriver deltas', ânot one iota', âomega-3 fatty acid' and Omega watches. I learned that Jesus was âalpha and omega'.

Here are the uses of just one of the letters, âlambda' (both forms). Please recite this at high speed:

a)

Â

the von Mangoldt function in number theory

b)

Â

the set of logical axioms in the axiomatic method of logical deduction in first-order logic

c)

Â

the cosmological constant

d)

Â

a type of baryon

e)

Â

a diagonal matrix of eigenvalues in linear algebra

f)

Â

the permeance of a material in electromagnetism

g)

Â

one wavelength of electromagnetic radiation

h)

Â

the decay constant in radioactivity

i)

Â

function expressions in the lambda calculus

j)

Â

a general eigenvalue in linear algebra

k)

Â

the expected number of occurrences in a Poisson distribution in probability

l)

Â

the arrival rate in queueing theory

m)

Â

the average lifetime or rate parameter in an exponential distribution (commonly used across statistics, physics, and engineering)

n)

Â

the failure rate in reliability engineering

o)

Â

the mean or average value (probability and statistics)

p)

Â

the latent heat of fusion

q)

Â

the Lagrange multiplier in the mathematical optimization method, known as the shadow price in economics

r)

Â

the Lebesgue measure denoting the volume or measure of a Lebesgue measurable set

s)

Â

longitude in geodesy

t)

Â

linear density

u)

Â

ecliptic longitude in astrometry

v)

Â

the Liouville function in number theory

w)

Â

the Carmichael function in number theory

x)

Â

a unit of measure of volume equal to one microlitre (1 μL) or one cubic millimetre (1 mm

3

)

y)

Â

the empty string in formal grammar

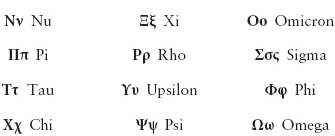

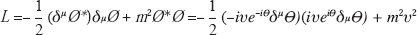

To get an idea of how mathematicians, physicists and engineers handle the Greek alphabet in their abstract thinking, here's a line from Goldstone's boson:

In 1964, I went to Middlesex Hospital Medical School. This came about as a consequence of a notion that had crossed my mind two years previously which went something like this: âI enjoyed doing Biology. What a shame I am now going into the sixth form to study English, French and History without doing any Biology.' I shared this notion with my parents who fell on it like an eagle on a lamb. âWe know what you would like to

do. You would like to be a doctor. Come and talk to our old doctor friend.' Any resemblance that this story has to stereotypes of Jewish parents longing for their offspring to be doctors, lawyers or accountants is purely coincidental. Or not.

The doctor friend explained that at the Middlesex Medical School, they welcomed people with little or no science background on a course called âFirst MB' where they would take you from 0 to 60 mph in Biology, Physics and Chemistry in a year. I could carry on with my English, French and History and then embark on years of science and medical study. So it was, two years later, I came off A-level courses in such things as Chaucer, Conrad, the unification of Italy and Voltaire to be hit by hours of rat dissection, photons and mitochondria. In the Physics lab I met the Greeks. It seemed to me at the time that the Greeks had named or labelled anything of any importance. I don't think I was fully aware at the time that it wasn't the Greeks who did this but the pioneers of scientific discovery. Like Young. And his modulus. Incredibly, we have already met Young in âA for Alphabet'. It was his work that helped Champollion decipher the Rosetta Stone.

Thomas Young was born into a Quaker family in Somerset in 1773. He learned French, Italian, Hebrew, German, Chaldean, Syriac, Samaritan, Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Amharic. He studied medicine, then moved on to studying Physics in Germany. With the help of an inheritance, he set himself up as a physician in London and became a professor of natural philosophy at the Royal Institution. He established the wave theory of light; he gave his name to âYoung's modulus' which enabled engineers to predict strain. He founded the study of the physiology of the eye and described the change of the curvature of the human lens, astigmatism and the eye's reception of colour. He deduced capillary action (water rising up a capillary), and was the first

to define âenergy' in its modern sense. He developed a system for determining children's dosage of medicines and derived a formula for the wave speed of the pulse of blood through arteries. He proposed a universal phonetic language, and introduced the term âIndo-European languages' by comparing the vocabulary of 400 languages. Shockingly, he wasn't entirely successful in cracking the hieroglyphic code on the Rosetta Stone, though Champollion, as we've seen, credited him with having made great progress by correctly finding the sound value of six of the hieroglyphs. Oh yes, and he also developed âYoung temperament' â a method of tuning musical instruments.

Young was clearly tiresomely brilliant at everything. I discovered while I was studying science, including his modulus, that I wasn't brilliant at science.

What I'm about to say is entirely from memory, so excuse me if I've got it wrong. I'm doing it as a way of testing to see if these important features of the known world have survived for fifty years in my head. We were given some springs. We attached one end to a hook and the other to a weight. The weight pulled on the spring so that it stretched. We measured how far. We attached heavier weights to springs. We drew a graph showing how the springs got longer if the weight was heavier.

Now the next bit gets hazy. Something was âsigma'. I think it was the relationship between the weight and the length of the spring. I think we were introduced to another variable: the thickness of the spring's wire. As I write this I am desperately hoping that I've got this right and that feeling is reminding me of how I felt doing First MB. It's a sense that there is a world of precision which reveals characteristics of the real world, but I live in a parallel world that is constantly beset with vagueness and indeterminacy. In an entirely illogical way, I have a sense that the precision world is precise because it uses Greek letters. Greek

letters name precisely observed features. Calculations can be made using these Greek letters which, in the case of that experiment, will enable engineers to calculate how thick the hawsers need to be on a suspension bridge. The Greekness of the letters is an essential part of how I feel about all this. I can hear my scientific brother talking about âsigma', âmu', âtheta' and âlambda' as entities. When he does Maths he can manipulate them in the precision world.

There's an irony here. Non-Greeks have used Greek letters to be scientifically precise and specific, yet the reason why Greek was chosen â and is still being chosen â is cultural. In Roman times, Greek was the language of teachers, and in art the Romans looked to the Greeks as their progenitors. In the medieval period, the two foundation languages were seen to be Latin and Greek, with Greek being the older. Early scientists were assumed to have a level of education which would include knowing the Greek letters. For the writers of fiction and the namers of new substances or new products, the key issue is connotation â that cloud of associations that runs through and around every word we say and write. Using a Greek letter lends the object, being or character a scientific identity. Because so much modern science is beyond the uninitiated, the association is not only with science but also with mystery, something that only true boffin-heads really know and understand. This is ideal for sci-fi, which likes to bundle up science, mysterious power and uniqueness into a single entity.

âBeta' has been enlisted as an acronym for âbeings of extra-terrestrial origin that are an adversary of the human race', in a video game, an organization in the TV series

The Adventures of the Galaxy Rangers

, and as the âBeta Quadrant' (part of the universe in

Star Trek

).

Another form of science fiction is written by the people who

invent the names and write the blurbs for products like the Sigma make of camera. The manufacturers boast that their product can help you to take âthe perfect image', using standards âabove and beyond industry norms', with lenses analysed by âultra-high definition sensors', built with âpremium materials'

So, what you're buying has a founding myth (from âday one', the puff says, referring to a point in time way back in 1961) and it involves âperfect' technology, that is beyond the normal, as it is âultra' and âpremium'. This manages to invoke both science and mystery. A Greek letter is ideal for this kind of sales push. And the results of a successful sales push could be expressed, I'm sure, with some kind of coefficient of expansion which would beg to be expressed with another Greek letter too.

“I

BEG YOUR PARDON

, M

A'AM, BUT

I

THINK YOU DROPPED THIS

?”

⢠SEE âH IS

for H-Aspiration'.

Sound-play with âh' includes âhigh hopes', âhave a happy holiday', âho ho ho', âhooray Henry', the âwhole hog', âcome hell or high water', âhigher and higher', donkeys go âhee-haw' and rap's precursor was âhip-hop'.

N

O OTHER LETTER

has such power in dividing people into opposing camps, whether in terms of how the letter is named or in how people pronounce words with the single letter âh' in them. The way to avoid civil war over these is to accept that what's on offer are âvariants', not rights and wrongs â but then saying this in itself can start wars too. My position is this: we don't have to take instructions or directions on either âaitch' or âhaitch', we can say âaitch'

and

âhaitch' and the sun won't fall out of the sky. Saying either or both doesn't harm anyone, doesn't destroy civilization, doesn't cause damage to property. Just as we can write âjudgement' or âjudgment' and the world goes on turning, so we can say âaitch' or âhaitch'. Even more dangerously and subversively, I'm happy to say that we can âaspirate' our Hs, or not aspirate them, or indeed pronounce them with or without a âglottal stop'.