Alphabetical (16 page)

Authors: Michael Rosen

Before print, those who could write the letters could also appear as if they owned the law and religion. They could turn pages and, by looking at the signs, they could reveal the difference between good and bad, or what could guide you, entertain you, fine you, terrify you, lock you up, or even take your life. If you couldn't read and write, you couldn't own any of this. When print was invented, new kinds of people elbowed their way into taking possession of it: merchants, tradesmen, teachers, artisans. Lords, masters and leaders could create laws; writers could

compose stories, plays and poems; master printers alone owned the secret skills to get the writing from hand-drawn script to printed page. Only they, really, knew the letteriness of each letter. That's how it stayed for 500 years, from Gutenberg to Letraset. Of course, there were writers, painters, designers and masons who could design letters but, without a printer, they couldn't distribute what they did.

Now, with our digitized, non-sticky Letraset, up on our computer screens, whiteboards, tablets and phones, the alphabet is a much more mutable, flexible tool. Even as teachers are asked to teach the correct way to write, the designers of machines are allowing people to choose what is the correct way to write. For a lot of the time, this may seem as if it's about layout or design, but behind it all lies the fact that the choice of letter (albeit from a fixed range) doesn't have to be made by someone other than you. The smallest building blocks of the shared written language (i.e. print) are more in your hands now than they have ever been. I suspect that this shift in the materials of how the written language reaches us is at the heart of why the language of writing is changing so fast. I explore this further in âT is for Txtspk'.

â¢

THE LETTER-SHAPE

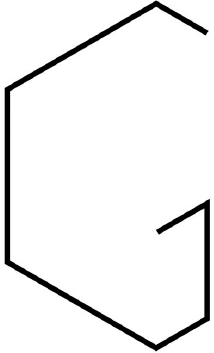

of âG' derives from the Greek letter âzeta' â a letter looking like our capital âI'. It was pronounced âz' which is how the Romans picked it up from the Etruscans. However, they didn't need a continuous âzzz' sound in Latin. Around 250

BCE

the Romans altered its shape to look more like an âE' without the middle horizontal stroke and it was at this point that they decided it wasn't a âzzz' but a âhard g' as in our word âgap' or in the Latin word âagricola' (one of the first words that I learned in Latin which I have put in here for old times' sake). The letter shape then curved to a crescent so that by the time it appears in classic Roman carved inscriptions in the second century

AD

it has the shape of our serif âG'.

There are two lower-case Gs: two storey and single storey. The two-storey âg' comes from the French typeface of the 1500s, Garamond; the sans-serif, single-storey âg' derives from the âCarolingian minuscule' drawn up by Charlemagne's scribes.

PRONUNCIATION OF THE LETTER-NAME

Because we can pronounce âg' in three different ways â the âg' of âgap', the âg' of âcourage', and the âg' that some represent as âzh', which is one of the pronunciations of the last âg' of âgarage' â we have to speculate why we say the âg' of the letter-name as âjee'. In Latin it was âgay', early French made it âjay'. The Great Vowel Shift turned it into âjee' â which is just as well given that âj' is pronounced

âjay'! (See â

J

' for why âG' and âJ' didn't kill each other in a fratricidal quarrel.)

PRONUNCIATION OF THE LETTER

The three pronunciations depend on when and how any given word appears in the language and then what changes people work upon it. When I studied Chaucer, we were alerted to the cool way in which he slots into his English a stream of words of French origin. The experts seem to know that words like âcourage' were pronounced at that time as âcoor-ah-zh-er', rather than modern-day âcurridge'. However, as you will have noticed, we don't write it as âcurridge'.

That â-dge' ending is one of the âtrigraphs' we have in English â meaning three letters indicating one sound.

âG' combines at the beginning of words with all the vowels and vowel ây' as in âgyre', along with âr' as in âgrip', and âl' as in âglad'. It's the closing letter of one of our most popular word endings, â-ing', which is pronounced as âhard g' in some parts of Britain, as a soft nasal combined sound in other parts, and not at all in London or in âold posh' as in âhuntin', shootin' and fishin''. Other ways of putting consonant sounds before âg' give us âbulge' and âsponge'.

We also have several kinds of silent âg': âgnat', âsign', âfight', âdelight' and even Gs that look as if they should be silent but are not, as in âgnu'.

âgnat': | owes its âg' to Old English âgnaett'. |

âsign': | owes its âg' to Old French âsigne' and before that, Latin âsignum'. |

âfight': | owes its âg' to French scribes rendering the guttural âch' sound as âgh'. |

âdelight': | owes its âg' to wise but foolish lexicographers demanding that âdelite' from Old French should look like âfight'. |

âgnu': | owes its âg' to German traveller Georg Forster (1754â1794) giving us âgnoo' from Dutch âgnoe', representing a native southern African word for a âwildebeast', âi-gnu'. |

However, the main reason for all this is to make children (and people for whom English is an additional language) cross, unhappy or both.

We play with the âg' sounds by saying someone is âga-ga'; people used to play with âgew-gaws'; Gigi was famous; you can bet on the âgee-gees' and say âGolly, gee' which is probably to do with âJesus'. We talk of âgo-getters' who may or may not have âget-up-and-go'. Something can âget my goat' and you can âgive it a go'. Some people used to sing: âGing-gang-goolie-goolie-goolie, ging gang goo . . .' The best way to offend a ventriloquist is to say, âGottle a geer'. Some people have âthe gift of the gab'.

A

S IS OFTEN

said, we owe the Greeks big-time.

First â vowels.

The words âfacetious' and âabstemious' have something in common: they contain all the vowels in the order in which they appear in the alphabet.

We are taught to say, âa, e, i, o, u are the vowels' as if this was something correct and significant. However, there are three problems:

1.

Â

If there really is something called a vowel sound, then the letter ây' is an invitation to say at least two: the ây' in âlovely' and the ây' in âfly'. âY' should get an invite to the party.

2.

Â

By far the most common vowel sound in spoken English is the âschwa'. Think how you say the âa' in the word âabout' in the phrase, âI'm about six feet tall.' It's time we had a âschwa' letter. On the basis of the rule that writing changes according to need, one day we will. The phonetic alphabet symbol for it is an upside-down âe'.

3.

Â

We make many more vowel sounds than there are âvowels'.

We represent vowel sounds by using the âvowels' singly, in twos, threes and using consonants as well.

The âschwa' was given its name by one of the Brothers Grimm â Jacob. It's everywhere. Most of the times we say the words âthe' and âa' we do the âschwa'. We like the âschwa'. The âschwa' is like a giant octopus that spreads over the whole of speech, sucking up thousands of words, replacing âay' and âee' and âeye' sounds with the same short noise. It is also one of the reasons why trying to teach reading purely and only according to the sounds that children make is not easy and, some would say, wrong: the âschwa' does uniformity where the letters do difference. To make the letters sound different, you end up âstressing' the unstressed words like âto', âthe' and âa', enunciating them as âtoo', âthee' and âay'. You start to sound stressed.

Vowel sounds are âopen mouth' sounds, where we open the mouth, often leaving the tongue sitting on the floor of the mouth. As we rattle along in speech, we alternate between âopen' sounds and ones where we âclose' the sound, using the back of the throat, tongue, lips or teeth or any of the three in combination with each other. We try to signify these closed sounds with consonant letters, used in ones, twos and threes (e.g. âf', âsh', and âstr') and occasionall

y with a vowel letter to guide us, as with âoccasionally' where the âsi' invites us to make a âzh' sound.

Similarly (to illustrate point 3 from above), a single vowel letter is not the only way we signify a vowel sound. We can do it with two vowel letters, as with âee', âou' and âoa'; with âsplit' vowel letters as with the âi' and âe' of âsite'; when guided by âsilent' consonant letters as with âfight'. We also put three vowel letters together in âbeauty' to make a sound very similar to âyou'. If you come from London, as I do, we also make vowel sounds when we see âar' in âbar'. We don't âstop' the vowel with the

consonant letter âr'. For me, the three letters in âoar' signify a vowel sound. Again, the way I pronounce the word âdeal' could be represented as something like âdee-oo' where the âal' indicates to me when I'm reading out loud that I should say âoo'.

Vowel letters have quite a lot to do with the Greeks.

One story goes that the Phoenician alphabet was consonants only. Then came the Greeks. They invented vowel letters.

The problems with this story are:

a)

Â

the late Phoenicians had already started to invent vowel letters;

b)

Â

the Greeks adapted four already existing Phoenician consonant letters to signify the equivalents of âa', âe', âi' and âo': âaleph' became âalpha', âheth' became âheta' (âepsilon' was added later), âyodh' became âiota', âayin' became âo' (later called âomicron' and âomega' â or âo little' and âo big'); and

c)

Â

they invented one vowel letter, the âu' (âupsilon').

The ancient Greeks get the credit for inventing everything from democracy to houmous, so maybe they can take this small downgrade in inventiveness.

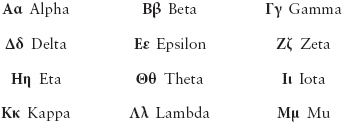

Now to the Greeks, their letters and the other world of the scientific alphabet. Here's the Greek one: