Alphabetical (18 page)

Authors: Michael Rosen

Glossary: âaspirate' = making a breathing-out sound at the beginning of a word like âhappy'; âglottal stop' = a speedy little constriction in the throat accompanied by an exhalation â a noise that can be the way some people pronounce ât' or âh' and

is sometimes represented in writing with an apostrophe, as in âbu'er' (butter), say.

Some people disapprove of glottals and non-aspirated Hs and call them âlazy'. Clearly, there is nothing lazy about constricting the back of your throat and producing a short, sharp exhalation. Because that particular way of producing sounds has been connected to people deemed to be of low status in society, the attitude that it's undesirable or lazy is nothing more or less than prejudice disguised as judgement.

Concerning the name of the letter itself: several observations are made about who says one rather than the other. More and more young people are saying âhaitch'. The two variants used to follow the religious divide in Northern Ireland â âaitch' amongst Protestants, âhaitch' amongst Catholics, mostly because that's how it was taught in the separate schools. Most schools in the Republic teach âhaitch'.

The letter-name doesn't have a clear etymology. To fit in regularly with the other letters, we might expect it to be âhay' or âhee', but it needs saying: nothing in language is 100 per cent regular. âH' owes its name to the Normans who came in saying that it was âhache' or âache' â perhaps because they too couldn't decide whether to aspirate the word or not. (If you can pronounce French, you'll know it as âush'.) âHache' is the origin of the English word âhatchet' and one theory is that this tool is described by the appearance of the lower-case âh'. The only other theory knocking around is that âhache' is derived from a Latin name that was never written down.

(The reason why etymologists can have theories like that is because not everything that the Romans said was written down and of course we have only written Roman, not spoken Roman, to go on. The Latin word for âhorse' is âequus' but all over Europe where Romance languages are spoken, people have

versions of a word for âhorse' that begins with a âc', has a âb' or âv' sound in the middle and an âl' sound at or towards the end. This suggests that there was a low-status word doing the rounds in Roman times â possibly âcaballus' â but it was so low status it never made it into any piece of writing that has survived.)

Back with âh': given that the sound we associate with âh' is so slight (a little out-breath), it'll be no surprise to know that there has been some debate since at least

AD

500 whether it was a true letter or not. Letters and sounds are so imprinted into the heads of fluent readers, it's always hard to think round a question like this. We have to remember that when we write we do not indicate all the sounds or variations in sounds that we make. What's more: though we write letters one after the other, the sounds we make blend into each other. Think of âskew' or âtrial'.

One consequence of using letters is that by themselves letters and combinations of letters cannot indicate variations in stress, rhythm and pitch. We leave it to musical notation to do that. If I were writing dialogue in a novel, and wanted to represent the end-of-phrase down-pitch of a Russian speaking English, or the end-of-phrase up-pitch of a young Australian, American or English person, I have no graphic way of representing that. âLoan words' sometimes survive in English with a trace of their origins: âlingerie' is now an English word and the âin' is usually given some kind of the nasalization that French people use though we have no way of indicating that. In other words, though there is an apparent precision about what sounds letters signify, on close examination it's all much more fluid than that. Most people do not say âlinn-jer-ree'. They say something like âlongzh-er-ee'. Our alphabet can't be that precise, particularly when it comes to loan words like âlingerie'.

So 1,500 years ago, Latin scholars noticed that what is peculiar about the breathy little sound of âh' is that it doesn't seem to be very distinct and that it overlaps with the next sound or even âcolours' it. (We might ask ourselves why the âh' in âhoot' is pronounced differently from the âh' in âhew'?). As Latin evolved in France, people decided to drop saying the âh' altogether, just as we say âour' when we mean or read âhour'. Formal French demands that distinctions are made between the two types of non-pronounced âh'. Getting it wrong was something that lost us marks in our French conversation exam in 1964. I can't look at a green bean in a French supermarket without pondering on how to say âles haricots'. In French, this is not a matter of whether or not to make the out-breath sound of âh'. It's a matter of how you make the sound in front of the âh'. Is it âlay urry-co' or âlaze urry-co'? Say the wrong one and you're doomed to ignominy. It's âlay urry-co'. Say âlaze urry-co' and they'll think you're over-correcting and trying to sound better than you are. Like I said, doomed to ignominy and you won't deserve the beans.

In Britain, there have been centuries of dispute about it. The most up-to-date research suggests that some of the dialects in thirteenth-century England were h-dropping but by the time elocution experts came along in the eighteenth century, they were pointing out what a crime it is. Pause for one particular absurdity in this: when words such as âhorrible', âhabit' and âharmony' first came into English from French, they weren't pronounced with the âh' sound. Nor were they originally spelled with an âh'! Yet, for some, saying â'orrible' is an error. Second absurdity: some âdropped aitches' are more of a crime than others. â'Appy birthday' is seen as more distinctively cockney, lower class and undesirable than âcould've' which almost all speakers say at some time or another. Of course, when people object to the way other people speak, it rarely has any linguistic

logic to it. It is nearly always because of the way that particular linguistic feature is seen to belong to a cluster of social features that are disliked. At times, this can get quite nasty. Over a hundred years ago, an adjective, âh-less', was in circulation and

The Times

and other polite newspapers used it to refer to such undesirables as âh-less Socialists' or the nouveau riche who made stacks of money but were still âh-less'.

If you want to imitate cockney or Jamaican speech, then one way to do it is to leave off the âh' in some words which are spelled with an âh', and to add an âh' to some words that have no initial âh'. Ted Johns, the tenants' leader on the Isle of Dogs in the East End of London, told me that when he was a boy in the 1930s, the class used to have to do elocution exercises in order to stamp out the âdropping of Hs'. âBe honest, humble and humane, hate not even your enemies,' they would chant. âEven now,' he told me in his fifties, âI get them muddled and say, “Be honest, 'umble and 'umane, 'ate not heven your henemies”.' Sticking âhonest' in that exercise was a cruel move, because that's where English has retained the French âh', as with âheir' and âhonour', and in US English âherb' and âhomage' with not a breathy sound within hearshot, I mean earshot. Why couldn't all these French âh' words have been lumped in with âostler' (meaning the man who works in a hostel) and âarbour' (once âherbier', the place where they grow grassy stuff)? Answer: because a lot of spelling â especially when it comes to the letter âh' â does not follow logic.

So âh' is not only rather a slight sound, but it wobbles about both in print and as it is spoken across different communities.

Poor Letter H, its uses and abuses

was the title of a little book jokily authored by âthe Hon. Henry H', published in 1859. âYou can't pass from Kensington to Mile End Gate,' writes the Hon. Henry, âwithout hearing thousands of well-dressed and ill-dressed

people, all alike, inflicting the greatest injuries upon these little letters, whose wrongs I have stepped forward to redress.' Henry travels about incognito and tells us that he has spotted people saying â'ock' and â'ouses' when they should be saying âhock' and âhouses' and others talking of the âhaims' and âhends' of their projected plans. Henry is pleased to report, however, that things are better in Northumberland, where people get it right.

In the book, the letter âH' sends a letter to the vowels (to their home in Alphabet Lodge from his home in Holly House, Hertfordshire) and tells them that he has the most âhonourable aspirations'. (That's my favourite gag in the book.) âI have heard,' says H, âthe little prattling child tell his mamma that he had “'

urt

his '

and”,

and to my surprise, his mother did not ask him what he meant.'

Are you picking up an ironic tone here? Was the Hon. Henry H someone having his cake and eating it â pretending to be censorious whilst pointing out some of the absurdities of the objectors?

H goes on to say that he's heard high-class and educated people talk about the âHottoman Hempire', and âhadvocate' causes when they had no right to mention him (i.e. to use the letter âh' in that context). H has heard a âshopman' offer a lady a â'andsome hopera dress', and a politician talk of âhagitate, hagitate, hagitate'. Someone, H claims, once suggested to Rowland Hill, the inventor of the postage stamp, that the letter âH' be abolished, to which Hill replied: if that happened, it would make him âill for the rest of his life'.

In his next letter to the vowels, H lays out a chart of correct pronunciation and there we see that he says the following words should not be aspirated: âheir', âhonest', âhonour', and âhour' (as indeed are unaspirated in our speech today), but also âherb', âhospital' and âhumble'. All other âh' words, he says, should be aspirated.

Put plainly then, if I had wanted to talk âcorrectly' in 1858, I should have said âerb', âospital' and âumble'. The âincorrect' aspiration of those three words somehow became âcorrect' aspiration by the time I was being corrected at school in the 1950s. By what strange processes did these transformations take place?

Much less contentiously, âh' is put to work in a lot of other ways too: think âch' and âsh'. When it combines with ât' to be âth', it runs into problems with some elocutionists who try to stamp out Londoners and âEstuary' speakers saying âfree' for âthree' and âfevver' for âfeather'. My youngest son got so confused by these attempts to match up the âf' sound to the letter âf' and only the letter âf' that he started pronouncing âf' words with a âth' sound: âfirst' became âthirst' and âdifficult' became âdithicult'. These âdigraphs' (two-letter combinations of letters) do the same job as many of our single letters: they indicate one clear sound. It used to do similar work in âwh' as in âwhat', making it all breathy, and it used to do work in âgh' as in âfight' but the Germanic âch' sound slipped away.

The exclamation âugh' uses âgh' to indicate the in-the-throat âch' at the end of âloch'. âH' appears in ârh' as in ârhino' and in âph' as in âphone' to remind knowledgeable people of their Greek origins and to make life hard for children trying to spell correctly. You can spot âh' digraphs in loan words: âbh' as in âbhindi' (okra or ladies' fingers), âdh' as in âdhow', âkh' as in the name âKhan', ânh' as in Viet-Minh, and âzh' as in âmuzhik' (a humble Russian peasant), which my mother used to call me in moments of affection. My favourite, though, is âyacht' where it pretends to be doing something very useful by doubling up with the âc' but ends up not doing very much at all. Modern phonics teaching would say that âach' in âyacht' is a way of saying the same sound as âo' in âhot'.

You could say that âH' is not doing a lot when we write âoh', because âo' sounds just the same as âoh'. The other way of looking at that is to say âoh' as a digraph does the same kind of work as âo' and âe' in the âsplit digraph' of âhope' but not the same as the âoh' in âJohn'. If you think this is complicated, don't blame me. You could say that âH' is doing a lot more than the âh' in âoh' when we write âah', âeh' and âuh' or even âuh-uh', as, some would say, it indicates how we should pronounce the vowel letter. To the new school of teaching, though, they are all digraphs which indicate vowel sounds in themselves. These are sounds not necessarily indicated by the five vowel letters on their own. Using âh' to create the digraph âah' tells us how to make this particular vowel sound. Ah, the phonetic philosophy of âh'.

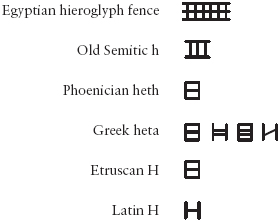

The shape of âH' has aroused interest because there seems to be a direct lineage from a hieroglyph for a fence, to an old Semitic letter, to Phoenician âheth', to Greek âheta', to Etruscan and then to Latin.