War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 (33 page)

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

German Panzer divisions may have been fearsome in the attack but they were less formidable when tied to static defensive tasks because they were short of infantry. An up-to-date Panzer operations manual, published just six months before the campaign, devoted 26 pages to the ‘Attack’, but only two paragraphs covered ‘Defence’.

(2)

Units not only lacked time when hastily organising defensive pickets, but also lacked the expertise needed to produce the sort of co-ordinated defence in depth recommended in infantry training manuals. Motorised units skilled in the art of mobile warfare did not have the eye for ground that experience conferred when selecting defensive positions. A young infantry Leutnant with the Ist Battalion of Panzergrenadier Regiment ‘Grossdeutschland’ explained the dilemma of having to create a defensive position near Smolensk by night:

‘The battalion had taken up a so-called security line spread improbably far apart. This was something new for us; we had never practised it. There was no defence, only security. But what if the enemy launched a strong attack?’

(3)

In France or Poland motorised units had generally superimposed a hasty and

ad hoc

screen consisting of primarily security pickets around an encircled enemy force. It did not work in Russia. Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock, commanding Army Group Centre, wrote with exasperation at the inevitable consequence on 20 July as the battles around Smolensk gathered momentum:

‘Hell was let loose today! In the morning it was reported that the enemy had broken through the Kuntzen corps at Nevel. Against my wishes, Kuntzen had sent his main fighting force, the 19th Pz Div, to Velikiye Luki, where it was tussling about uselessly. At Smolensk the enemy launched a strong attack during the night. Enemy elements also advanced on Smolensk from the south, but they ran into the 17th Pz Div and were crushed. On the southern wing of the Fourth Army the 10th Motorised Division was attacked from all sides and had to be rescued by the 4th Panzer Division. The gap between the two armoured groups east of Smolensk has still not been closed!’

(4)

Hubert Goralla was a

Sanitätsgefreiter

with the 17th Panzer Division caught up in the desperate fighting alongside the Minsk-Moscow

Rollbahn

leading into Smolensk. Russian break-out attempts were on the point of collapse.

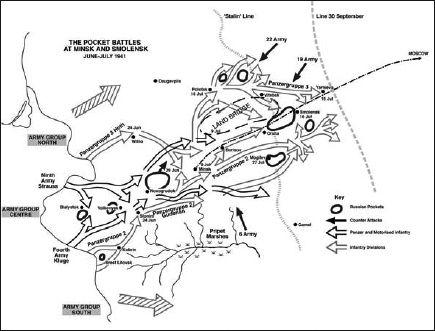

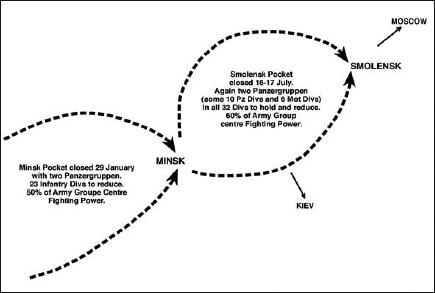

Generalfeldmarschall von Bock was ordered prematurely to close the Army Group Centre armoured pincers on Minsk (300km from Brest-Litovsk) at the end of June, when his preference was to push further east and create an even bigger pocket stretching 500km to Smolensk. His two Panzergruppen came together at Minsk, employing 23 German infantry divisions after the initial encirclement on 29 June. 50% of Army Group Centre’s fighting power was thus tied up until the pocket capitulated on 9 July. Nevertheless, sufficient momentum had been achieved by the remainder of army Group Centre close to the Smolensk pocket on 17 July. The Russians unexpectedly fought on, tying down 60% of the army group’s offensive fighting power until 11 August. Despite staggering Soviet losses, the Blitzkrieg momentum had run out of steam just beyond the Smolensk land bridge’, the jumping-off point for any assault on moscow.

‘It was absolutely pointless. The [

Russian

] wounded lay left and right of the Rollbahn. The third attack had crumpled in our fire and the severely injured were howling so dreadfully it made my blood run cold!’

After treating their own wounded, Goralla was ordered forward with two grenadier medics to deal with the Russian casualties ‘lying as thick as herring in a box’ in a hollow off the road. The medics, who were wearing Red Cross armbands, approached to within 20m of the hollow when the Russian wounded began to shoot at them. Two medics collapsed and Gefreiter Goralla waved those following behind to crawl back. As he did so:

‘I saw the Russians coming out of the hollow, crawling and hobbling towards us. They began to throw hand-grenades in our direction. We held them off with pistols we had drawn from our holsters and fought our way back to the road.’

Later that day the same wounded were still persistently firing at the road. A staff captain threatened them back with a pistol and stick. They took no notice. ‘Ten minutes later,’ said Goralla, ‘it was settled.’ A Panzergrenadier platoon went into the attack and cleared the area around the road.

‘Every single wounded man had to be fought to a standstill. One Soviet sergeant, unarmed and with a severely injured shoulder, struck out with a trench spade until he was shot. It was madness, total madness. They fought like wild animals – and died as such.’

(5)

Containing the Smolensk pocket, in the face of such pressure, became an obsession for von Bock. ‘At the moment,’ he wrote on 20 July, ‘there is only one pocket on the Army Group’s front! And it has a hole!’

(6)

The Panzer ring holding it, lacking strong infantry support, was extremely porous. Without the attached Luftwaffe anti-aircraft batteries, originally configured to protect the Panzers against air attack, the defence situation would have been even more alarming. High-velocity 88mm Flak guns were switched from air defence to the ground role. An example of their effectiveness is revealed by 7th Panzer Division’s defensive battle tally against 60–80 attacking Russian tanks on 7 July. Just under half – 27 of 59 enemy tanks – were knocked out by Flak Abteilung 84. Of the remaining 29 kills, 14 were knocked out by five other infantry units and 15 by the division’s Panzerjäger Abteilung (also equipped with Flak guns).

(7)

On 21 July von Bock grudgingly acknowledged the pressure the enemy was applying to his closing ring, ‘a quite remarkable success for such a badly battered opponent!’ he admitted. The encirclement was not quite absolute. Two days later Bock complained, ‘we have still not succeeded in closing the hole at the east end of the Smolensk pocket.’

(8)

Five Soviet divisions made good their escape that night, through the lightly defended Dnieper valley. Another three divisions broke out the following day. Unteroffizier Eduard Kister, a Panzergrenadier section commander, fought with the 17th Panzer Division near Senno and Tolodschino against break-out attempts mounted by the Sixteenth Soviet Army.

‘They came in thick crowds, without fire support and with officers in front. They bellowed from high-pitched throats and the ground reverberated with the sound of their running boots. We let them get to within 50m and then started firing. They collapsed in rows and covered the ground with mounds of bodies. They fell in groups, despite the fact the ground being undulating offered good protection from fire, but they did not take cover. The wounded cried out in the hollows, but still continued to shoot from them. Fresh attack waves stormed forward behind the dead and pressed up against the wall of bodies.’

Schütze Menk, serving in a 20mm Flak company with the ‘Grossdeutschland’ Regiment, described the desperate need to keep all weapons firing in the face of such suicidal mass assaults.

‘Our cannon had to be fed continually; flying hands refilled empty ammunition clips. A barrel change, a job that had to be done outside the protection of the armour plate, was carried out in no time. The hot cannon barrel raised blisters on the hands of those involved. Hands were in motion here and there, calls for full clips of ammunition, half deaf from the ceaseless pounding of the gun… there was no time to feed hidden fears by looking beyond one’s task, the Russians were unmistakably gaining ground.’

(9)

Kister maintained it was a totally unnerving experience. ‘It was as if they wanted to use up our ammunition holdings with their lives alone.’ His sector was attacked 17 times in one day.

‘Even during the night they attempted to work their way up to our position utilising mounds of dead in order to get close. The air stank dreadfully of putrefaction because the dead start to decompose quickly in the heat. The screams and whimpering of the wounded in addition grated on our nerves.’

Kister’s unit repelled another two attacks in the morning. ‘Then we received the order to move back to prepared positions in the rear.’

(10)

Pockets were not only porous, they moved. As Red Army units continually sought to escape, German Panzers had frequently to adjust positions to maintain concentric pressure or bend as they soaked up attacks. ‘Wandering pockets’ complicated the co-ordination of hasty defence and especially the reception of march-weary reinforcing infantry units moving up to form the inner ring. Infantry divisions moving behind Panzergruppen fared particularly badly. They were often obliged to change direction at little notice onto secondary routes to avoid Panzer countermeasures rapidly manoeuvring along the primary or supply arteries. Movement in such fluid situations was perilous, as described by Feldwebel Mirsewa travelling with one 18th Panzer Division convoy:

‘Suddenly they were there. Even as we heard the engine noises it was already too late. Soviet T-26 and T-34 tanks rolled, firing uninterruptedly, parallel to our supply convoy. Within seconds all hell had broken loose. Three lorries loaded with ammunition driving in the middle of the column blew up into the air with a tremendous din. Pieces of vehicle sped over us, propelled on their way by the force of the explosions.’

Men cried out and horses stampeded in all directions, running down anything that stood in their way. Suddenly the Russian tanks changed direction and swept through the column, firing as they went.

‘I will never forget the dreadful screams of the horses that went under the tracks of the tanks. A tanker lorry completely full with tank fuel burst apart into orange-red flames. One of the manoeuvring T-26 tanks came too close and disappeared into the blaze and was glowing incandescently within minutes. It was total chaos.’

A 50mm PAK was rolled up from the rear and quickly immobilised two of the heavier T-34 tanks, hitting their tracks. Both began to revolve wildly, completely out of control in the surreal battle now developing. Meanwhile, the lighter and faster T-26 types had shot every vehicle in the column into flames. Bodies of men who had attempted to flee their vehicles were strewn across the road. ‘I heard the wounded cry out,’ recalled Mirsewa, ‘but not for long, as the Russian tank clattered up and down over the dead and injured.’ A platoon of Panzergrenadiers with additional anti-tank guns drove up and swiftly set to work. At first the unmanoeuvrable T-34s were despatched. The scene began to resemble Dante’s ‘Inferno’ as the T-26s still engaging the burning vehicles were attacked.

‘The crack of detonations mixed with the tearing sound of huge tongues of flame. Metal parts whirled through the air. In between, machine guns hammered out as the grenadiers first engaged tank vision slits before their destructive high explosive charges were brought to bear. The chaos intensified into an inferno. Everywhere tanks were exploding into the air. Burning steel colossuses melted alongside our blazing supply column forming a long wall of flame.

‘The heat radiating across the road and reaching our position was hardly bearable. Worse of all, though, was the sight of numerous dead from our column lying in the road. Just as well our people back home will never get to know how their boys met their deaths.’

(11)

Containing ‘wandering pockets’ appeared an insurmountable problem. Von Bock reacted belligerently to the ‘Führer’s ideas on the subject, the gist of which was that for the moment we should encircle the Russians tactically wherever we meet them, rather than with strategic movements, and then destroy them in small pockets’.

(12)

This implied Blitzkrieg sweeps should be subordinated to minor tactical actions. With it came the realisation that the increasing gap developing between Panzers and infantry was annulling the previously proven benefits of a combined arms advance. Panzers were not robust in defence while infantry were insufficiently protected on the move.