The Double Dream of Spring

Read The Double Dream of Spring Online

Authors: John Ashbery

Poems

John Ashbery

Variations, Calypso and Fugue on a Theme of Ella Wheeler Wilcox

Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape

Long before they were ever written down, poems were organized in lines. Since the invention of the printing press, readers have become increasingly conscious of looking at poems, rather than hearing them, but the function of the poetic line remains primarily sonic. Whether a poem is written in meter or in free verse, the lines introduce some kind of pattern into the ongoing syntax of the poem’s sentences; the lines make us experience those sentences differently. Reading a prose poem, we feel the strategic absence of line.

But precisely because we’ve become so used to looking at poems, the function of line can be hard to describe. As James Longenbach writes in

The Art of the Poetic Line

, “Line has no identity except in relation to other elements in the poem, especially the syntax of the poem’s sentences. It is not an abstract concept, and its qualities cannot be described generally or schematically. It cannot be associated reliably with the way we speak or breathe. Nor can its function be understood merely from its visual appearance on the page.” Printed books altered our relationship to poetry by allowing us to see the lines more readily. What new challenges do electronic reading devices pose?

In a printed book, the width of the page and the size of the type are fixed. Usually, because the page is wide enough and the type small enough, a line of poetry fits comfortably on the page: What you see is what you’re supposed to hear as a unit of sound. Sometimes, however, a long line may exceed the width of the page; the line continues, indented just below the beginning of the line. Readers of printed books have become accustomed to this convention, even if it may on some occasions seem ambiguous—particularly when some of the lines of a poem are already indented from the left-hand margin of the page.

But unlike a printed book, which is stable, an ebook is a shape-shifter. Electronic type may be reflowed across a galaxy of applications and interfaces, across a variety of screens, from phone to tablet to computer. And because the reader of an ebook is empowered to change the size of the type, a poem’s original lineation may seem to be altered in many different ways. As the size of the type increases, the likelihood of any given line running over increases.

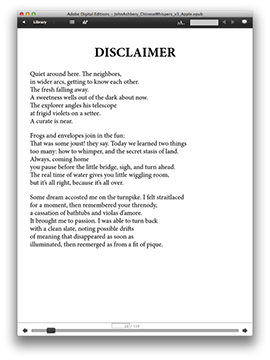

Our typesetting standard for poetry is designed to register that when a line of poetry exceeds the width of the screen, the resulting run-over line should be indented, as it might be in a printed book. Take a look at John Ashbery’s “Disclaimer” as it appears in two different type sizes.

Each of these versions of the poem has the same number of lines: the number that Ashbery intended. But if you look at the second, third, and fifth lines of the second stanza in the right-hand version of “Disclaimer,” you’ll see the automatic indent; in the fifth line, for instance, the word

ahead

drops down and is indented. The automatic indent not only makes poems easier to read electronically; it also helps to retain the rhythmic shape of the line—the unit of sound—as the poet intended it. And to preserve the integrity of the line, words are never broken or hyphenated when the line must run over. Reading “Disclaimer” on the screen, you can be sure that the phrase “you pause before the little bridge, sigh, and turn ahead” is a complete line, while the phrase “you pause before the little bridge, sigh, and turn” is not.

Open Road has adopted an electronic typesetting standard for poetry that ensures the clearest possible marking of both line breaks and stanza breaks, while at the same time handling the built-in function for resizing and reflowing text that all ereading devices possess. The first step is the appropriate semantic markup of the text, in which the formal elements distinguishing a poem, including lines, stanzas, and degrees of indentation, are tagged. Next, a style sheet that reads these tags must be designed, so that the formal elements of the poems are always displayed consistently. For instance, the style sheet reads the tags marking lines that the author himself has indented; should that indented line exceed the character capacity of a screen, the run-over part of the line will be indented further, and all such runovers will look the same. This combination of appropriate coding choices and style sheets makes it easy to display poems with complex indentations, no matter if the lines are metered or free, end-stopped or enjambed.

Ultimately, there may be no way to account for every single variation in the way in which the lines of a poem are disposed visually on an electronic reading device, just as rare variations may challenge the conventions of the printed page, but with rigorous quality assessment and scrupulous proofreading, nearly every poem can be set electronically in accordance with its author’s intention. And in some regards, electronic typesetting increases our capacity to transcribe a poem accurately: In a printed book, there may be no way to distinguish a stanza break from a page break, but with an ereader, one has only to resize the text in question to discover if a break at the bottom of a page is intentional or accidental.

Our goal in bringing out poetry in fully reflowable digital editions is to honor the sanctity of line and stanza as meticulously as possible—to allow readers to feel assured that the way the lines appear on the screen is an accurate embodiment of the way the author wants the lines to sound. Ever since poems began to be written down, the manner in which they ought to be written down has seemed equivocal; ambiguities have always resulted. By taking advantage of the technologies available in our time, our goal is to deliver the most satisfying reading experience possible.

They are preparing to begin again:

Problems, new pennant up the flagpole

In a predicated romance.

About the time the sun begins to cut laterally across

The western hemisphere with its shadows, its carnival echoes,

The fugitive lands crowd under separate names.

It is the blankness that follows gaiety, and Everyman must depart

Out there into stranded night, for his destiny

Is to return unfruitful out of the lightness

That passing time evokes. It was only

Cloud-castles, adept to seize the past

And possess it, through hurting. And the way is clear

Now for linear acting into that time

In whose corrosive mass he first discovered how to breathe.

Just look at the filth you’ve made,

See what you’ve done.

Yet if these are regrets they stir only lightly

The children playing after supper,

Promise of the pillow and so much in the night to come.

I plan to stay here a little while

For these are moments only, moments of insight,

And there are reaches to be attained,

A last level of anxiety that melts

In becoming, like miles under the pilgrim’s feet.

The immense hope, and forbearance

Trailing out of night, to sidewalks of the day

Like air breathed into a paper city, exhaled

As night returns bringing doubts

That swarm around the sleeper’s head

But are fended off with clubs and knives, so that morning

Installs again in cold hope

The air that was yesterday, is what you are,

In so many phases the head slips from the hand.

The tears ride freely, laughs or sobs:

What do they matter? There is free giving and taking;

The giant body relaxed as though beside a stream

Wakens to the force of it and has to recognize

The secret sweetness before it turns into life—

Sucked out of many exchanges, torn from the womb,

Disinterred before completely dead—and heaves

Its mountain-broad chest. “They were long in coming,

Those others, and mattered so little that it slowed them

To almost nothing. They were presumed dead,

Their names honorably grafted on the landscape

To be a memory to men. Until today

We have been living in their shell.

Now we break forth like a river breaking through a dam,

Pausing over the puzzled, frightened plain,

And our further progress shall be terrible,

Turning fresh knives in the wounds

In that gulf of recreation, that bare canvas

As matter-of-fact as the traffic and the day’s noise.”

The mountain stopped shaking; its body

Arched into its own contradiction, its enjoyment,

As far from us lights were put out, memories of boys and girls

Who walked here before the great change,

Before the air mirrored us,

Taking the opposite shape of our effort,

Its inseparable comment and corollary

But casting us farther and farther out.

Wha—what happened? You are with

The orange tree, so that its summer produce

Can go back to where we got it wrong, then drip gently

Into history, if it wants to. A page turned; we were

Just now floundering in the wind of its colossal death.

And whether it is Thursday, or the day is stormy,

With thunder and rain, or the birds attack each other,