War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

War Without

Garlands

Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942

Robert Kershaw

This book is dedicated to my three sons

Christian, Alexander and Michael

First published 2000

Paperback edition first published 2008

Reprinted 2009

This impression 2010ISBN 978 07110 3590 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

© Robert Kershaw 2000

The right of Robert J. Kershaw to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Ian Allan Publishing,

Riverdene Business Park, Molesey Road,

Hersham, Surrey, KT12 4RG.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by Mackays of Chatham, Kent.

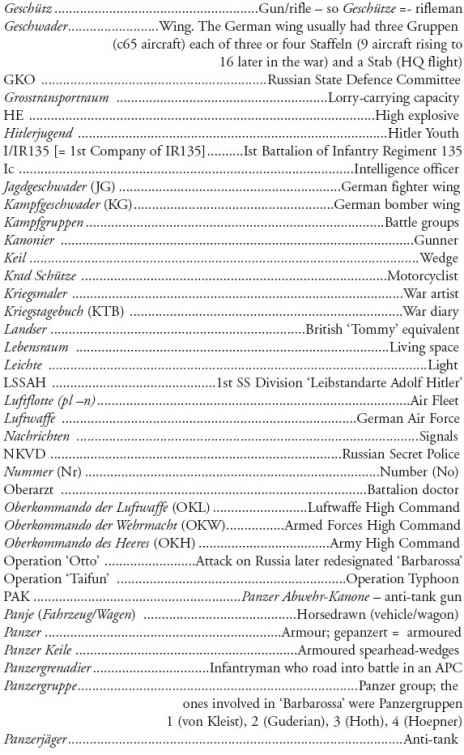

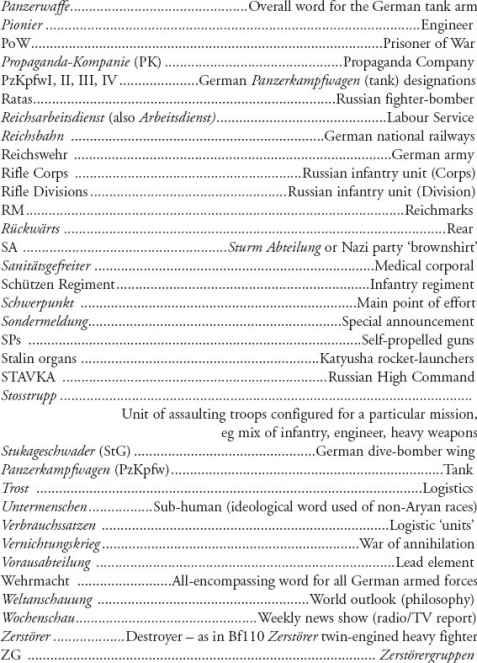

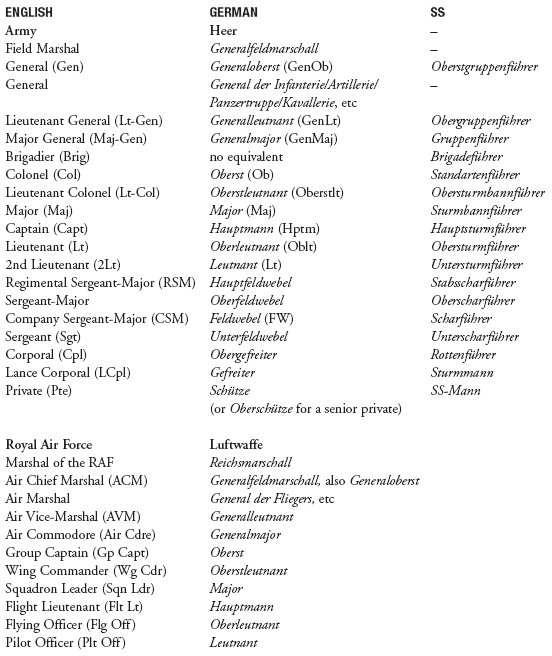

ContentsGlossary, Abbreviations and Rank Comparisons

Chapter 1: ‘The world will hold its breath’

Chapter 2: ‘Ordinary men’ – the German soldier on the eve of ‘Barbarossa’

‘Prepared… to face what is coming!’

The German Army, June 1941Chapter 3: The Soviet frontier

‘We’ve never had such a situation… Will there be any instructions?’

Chapter 5: The longest day of the year

‘Don’t die without leaving a dead German behind you’… Brest-Litovsk

Chapter 9: Refocusing victory conditions

Chapter 10: A war without garlands

Chapter 11: ‘Kesselschlacht’ – victory without results

Chapter 12: ‘Victored’ to death

Chapter 14: ‘The eleventh hour’

Chapter 15: The spires of Moscow

Chapter 16: The devil loose before Moscow

The German soldier does not go ‘Kaputt!’…

The crisis of confidenceChapter 17: The order of the frozen flesh

Postscript – ‘Barbarossa’ Notes to the text

1. German casualties Operation ‘Barbarossa’ 1941–42

2. German casualties reflected in division manning equivalents

3. The fighting elements within a German division

Glossary, Abbreviations,

Rank Comparisons

IntroductionNobody has written a definitive ‘soldier’s’ account of Operation ‘Barbarossa’. Academic historians and survivors writing on the Russo-German war of 1941–45 generally concentrate on military operations and have often ducked uncomfortable moral issues, or concentrated on one area to the exclusion of the other. I read with interest Paul Kohl’s comments retracing the footprints of the invading Army Group Centre during a historical pilgrimage through Russia in the 1980s.

(1)

Of 35 Wehrmacht veterans he contacted to assist in the project, only three admitted to having participated in excesses during the conflict. At the other end of the extreme is the

Vernichtungskrieg

(War of Annihilation) public exhibition travelling the length and breadth of present-day Germany seeking to publicise and lay clear blame for war guilt on the Wehrmacht. The significance is that the present-day

Bundeswehr

(the Federal Republic of Germany’s Army) developed from the Wehrmacht after the war. There is no shortage of epic and heroic tales from German survivors, who rarely saw an atrocity. Conversely the equally stirring Russian rhetoric of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ tells a similar tale of heroism from a political and ideological perspective. An honest account is that of a Wehrmacht veteran who admitted during a TV interview, ‘if some people say that most Germans were innocent, I would say they were accomplices’.

(2)There are varying degrees of accountability in war and they need to be examined. War guilt has been painstakingly examined by social democratic academics assessing the culpability of American soldiers fighting in Vietnam, Frenchmen during post-colonial conflicts in Algeria and the British in the Falklands. Moral issues are not as black and white as some learned authors would have us believe. Even UN and NATO soldiers have recently discovered in the Balkans that moral responsibility during conflict is a little blurred around the edges. The Russo-German war was fought between two totalitarian and ideologically motivated enemies, which produced a degree of ‘peer pressure’ upon combatants, frequently misunderstood by modern democratic historians who have never experienced it. Helmut Schmidt, a former German war veteran and later German Chancellor, once rounded on academic historians during a newspaper interview, pointing out they should not accept every document suggesting war guilt at face value.

(3)

Not every German at the front, he insisted, was a witness to atrocities.Documents are truths in the purist sense. Perception is also truth because it is an imperative that causes us to act. This is then why attempts are made in this book, through personal, letter and diary accounts, to narrate, observe and identify the beliefs and concerns that motivated the soldiers. They are about perceptions that became truths in themselves.

How can one explain or indeed reconcile the Christian statements of soldiers, seemingly decent men, about to go to war, with the systematic maltreatment and murder of Soviet PoWs and non-combatants? That war is a brutal process and corrupts its participants is not the sole explanation. There was an undercurrent of emotion impacting on incidents that caused brave men to act in a criminal way. Only by viewing these ‘snapshots’ of experience can one identify the emotions, perceptions and motivation of soldiers fighting a pitiless war in a strange land. The title ‘War Without Garlands’ is a play on a

Landser

expression used to describe this war. Soldiers referred to it as

‘Kein Blumenkrieg’,

a war without flowers. Quite literally flowers were not thrown in salute by an adoring public, as in the case of triumphant parades in Berlin, acknowledging Blitzkrieg victories after the campaign in the West.This book accepts that war is an intensely personal experience. Memories of conflict come in momentary glimpses or ‘snapshots’, and that is the style adopted. Concentrating on the five human senses brings a form of immediacy to the events being narrated. In addition, one must assess the soldier’s psyche through a medium of practical experience, placing ideological influences within a rational perspective. This is attempted by interpreting extensive diary and letter accounts.

It is important to measure the impact of these events, because, of some 19 to 20 million soldiers who fought for the Wehrmacht, about 17–19 million fought in Russia. These men were to form the basis of the future state established in present-day Germany, numbered among the most enlightened and democratic in the world. The book is an examination of the beginnings of a crucible of experience that was to influence these men throughout their adult lives.

The spelling of individual personalities and place names has been difficult to unravel from the multiplicity of Russian, German and English sources through which I worked. Many of the latter have changed since the end of the war. In general I have used the English version or German in the absence of an alternative.

Every effort has been made to trace the source and copyright holders of the maps and illustrations appearing in the text, and these are acknowledged where appropriate. Most are my own. Similarly the author wishes to thank those publishers who have permitted the quotation of extracts from their books. Quotation sources are annotated in the notes that follow the text. My apologies are offered in advance to those with whom, for any reason, I have been unable to establish contact.

I am particularly indebted for information and documents provided by Bundeswehr colleagues and contacts from within various NATO HQs, who assisted in the book’s long research and gestation period. My thanks also go to: the Panzerschule at Münsterlager and the Pionierschule at Munich; to Herr Michael Wechtler for access to a remarkable collection of documents and an informative 45th Division video chronicling the fall of Brest-Litovsk and to Dr Kehrig from the Bundesarchiv at Freiburg who assisted with important contacts, including Franz Steiner who enabled access to information and former members of the 2nd (Vienna) Panzer Division. Sheila Watson, my agent, has been very patient, gently reminding me during a series of overseas postings and operational tours that this book will never finish of its own accord.

My wife Lynn enabled the project to come to fruition by supporting me throughout. In typing the manuscript she applied her impressive eye for detail, clarity and grammatical accuracy. Any errors remaining are those I refused to change!

Without her, this book would quite simply never have been written.

Robert Kershaw

Salisbury, 2000