Trigger Point Therapy for Myofascial Pain (24 page)

Read Trigger Point Therapy for Myofascial Pain Online

Authors: L.M.T. L.Ac. Donna Finando

Iliopsoas and trigger points

I

LIOPSOAS

Proximal attachment:

Anterior bodies and intervertebral discs of T12âL5; upper two-thirds of the iliac fossa.

Distal attachment:

Lesser trochanter of the femur.

Action:

Flexion of the thigh at the hip when the torso is fixed; flexion of the hip on the thigh when the thigh is fixed; assists in extension of the lumbar spine (increasing lordosis) in the standing position.

Palpation:

Iliopsoas is comprised of three muscles: iliacus, psoas major, and psoas minor. These are muscles of the posterior abdominal wall. Together they act as the strongest flexor of the thigh at the hip. The depth at which iliopsoas lies makes it extremely difficult to palpate these muscles throughout their course, however a small portion of the attachment onto the lesser trochanter may be palpable.

To locate iliopsoas, identify the following structures:

- Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS)âAnterior bony projection lying somewhat below the iliac crest, readily palpable. The ASIS serves as the proximal attachment of the inguinal ligament.

- Rectus abdominisâSee muscle description on page 143.

- Femoral triangleâBounded superiorly by the inguinal ligament, medially by adductor longus (see muscle description on page 181), and laterally by sartorius (see muscle description on page 191). The floor of the femoral triangle is formed medially by pectinius and laterally by iliopsoas. Within this triangle the femoral pulse can be palpated 2 to 3 centimeters (approximately 1 inch) inferior to the inguinal ligament, at the midline of the base of the triangle that it forms. Both the femoral artery and femoral lymph glands lie superficial to iliopsoas and pectinius, which themselves lie superficial to the hip joint. The femoral artery lies just superficial to the head of the femur. The pulse point of the femoral artery can be palpated just superficial to the head of the femur, inferior to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament.

Image the placement of iliopsoas deep within the abdomen, lying just lateral to the vertebral bodies of T12âL5, passing to the inner aspects of the ilium, and attaching to the lesser trochanter of the femur. To palpate the most distal fibers of iliopsoas, abduct the thigh, flexing the lower leg. Locate the femoral triangle. Palpate iliopsoas at the lateral aspect of the floor of the triangle, medial to sartorius and slightly distal to the inguinal ligament.

Due to the sagittal depth of this muscle, success in palpating and treating a constricted iliopsoas is somewhat elusive. However, we have found that marked changes of the iliopsoas can be obtained by affecting the iliopsoas fascia at the lateral one-half of the inguinal ligament. By using acupuncture needling or direct digital pressure close to the distal portion of the attachments of these muscles at the ASIS and the lateral aspect of the inguinal ligament, the homolateral iliopsoas can be significantly released.

Releases of constriction in the upper fibers of iliopsoas can be obtained through the application of pressure or needling techniques through the abdomen, at the level of the navel, lateral to the border of rectus abdominis. Pressure should be applied medially and obliquely toward the midline.

Iliopsoas (anterior) pain pattern

Iliopsoas (posterior) pain pattern

Pain pattern:

Vertical pain that is worsened by weight-bearing activities and relieved by rest; relief is greatest when the hip is flexed. Upper trigger point refers unilaterally on the side of the trigger point with pain, extending from T12 to the ilium and upper buttock; lower trigger points refer pain to the groin and the anterior aspect of the upper thigh. Symptoms may include the inability to stand upright.

Causative or perpetuating factors:

Sitting for extended periods of time with the hips acutely flexed.

Satellite trigger points:

Quadratus lumborum, rectus abdominis, tensor fascia latae, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, thoracolumbar paraspinals, piriformis.

Affected organ systems:

Genitourinary and digestive systems.

Associated zones, meridians, and points:

Ventral zone; Foot Yang Ming Stomach meridian, Foot Shao Yang Gall Bladder meridian; ST 25, GB 27 and 28.

Stretch exercises:

- Lying on a table or bed, abduct the thigh and leg of the affected side and allow the limb to hang off the side of the table or bed. Flex the thigh and leg of the unaffected side to fix the pelvis, keeping the lumbar spine flat on the table or bed. Allow gravity to stretch the upper groin area. Hold for a count of twenty to thirty.

- Cobra: Lying prone, place the hands palms down at the level of the chest. Raise the upper body, supporting it with the weight on the arms. Arch the head and neck toward the ceiling, keeping the hips, legs, and feet relaxed on the floor. Hold for a count of twenty to thirty.

Release the stretch by relaxing the arms, bending the elbows to support the upper body weight, and slowly bringing the body down to the prone position.

Strengthening exercise:

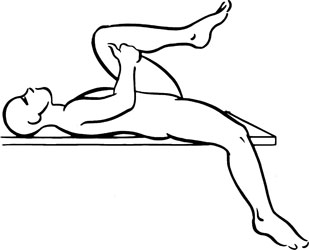

Leg lifts: Lie on the floor in the supine position. Place the hands, palms down, under the buttocks, reducing the lumbar arch and bringing it into contact with the floor. (It is essential to make certain that the lumbar region remains in contact with the floor in order to reduce the risk of injury to the back in this exercise.) From this position, raise the legs, knees slightly bent, approximately 12 inches and then return them to the starting position.

Repeat eight to ten times.

Stretch exercise 1: Iliopsoas

Stretch exercise 2: Iliopsoas

Rectus abdominis and trigger points

R

ECTUS

A

BDOMINIS

Proximal attachment:

Cartilages of ribs 5, 6, and 7; xiphoid process.

Distal attachment:

Crest of the pubic bone.

Action:

Flexion of the trunk; upward rotation of the pelvis.

Palpation:

The abdominal muscles form a continuous sheath within which lie the abdominal viscera. This sheath is bounded superiorly by the diaphragm; posteriorly by the psoas; posterolaterally by quadratus lum-borum; anterolaterally by transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique (moving deep to superficial); and anteriorly by rectus abdominis. The muscles of the pelvic floor form the inferior boundary of this sheath.

By and large, rectus abdominis and the other abdominal musclesâexternal oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominisâare difficult to distinguish from one another unless one is in a state of contraction or harbors taut bands. For the purposes of the treatment of myofascial constrictions within this group it is recommended that the patient's experience of pain be the guide that directs the practitioner's hands to the areas that may harbor constrictions. That is, palpation should begin where the patient describes his pain or discomfort to be. Palpation should be gentle enough to examine the abdominal musculature without forcing through it to the underlying viscera.

To locate rectus abdominis, identify the following structures:

- Xiphoid process

- Cartilages of ribs 5, 6, and 7

- Crest of the pubic bone

- Linea alba (white line)âTendinous union of the bilateral aponeuroses of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles, lying deep to the skin in the midline of the torso

Palpate rectus abdominis from the proximal attachment at the costal cartilages to the distal attachment at the pubic bone, following the vertical course of the muscle fibers. Place the hands, flat and relaxed, on the abdomen, with the fingers lying parallel to the direction of rectus abdominis; note the linea alba in the midline. The lateral boundary of the rectus abdominis is readily palpable in muscularly developed people. Note the segments into which the rectus abdominis is divided. Palpate rectus abdominis throughout its course for taut bands.

Rectus abdominis (anterior) pain pattern