The Thing with Feathers (4 page)

Read The Thing with Feathers Online

Authors: Noah Strycker

We tend to think of pigeons as indifferent, consistent, and pretty dumb creatures, hardwired in some mysterious way, but we probably don’t give them enough credit for intelligence. Birds are not mechanical missiles. Each one has its own personality, and is apt to make different decisions than another with separate genetics and history. Rather than relying on any one method, pigeons probably use all the tools at their

disposal—landmarks, sun, stars, polarized light, magnetic fields, smell, infrasound, and anything else that might help—to return home as best they can while being repeatedly stranded by their owners. These birds are most remarkable in the way they process information, which comes pretty close to the definition of intelligence. But they’re not infallible.

Though pigeons are celebrated for their ability to return home from any point on the map, there are a couple of exceptions—places on the landscape that for whatever reason seem to confuse the birds. One location in New York, called Jersey Hill, became famous as a trouble spot for pigeons in Cornell University ornithology experiments during the 1980s. Some believed it was a place of magnetic field anomalies, which would trip up pigeons’ magnetic sense. More recently, researchers have mapped infrasound in the area, and concluded that Jersey Hill lies in a sound shadow, a quiet spot where low-frequency sound from the home loft doesn’t reach. And a spot in eastern England has become known among pigeon fanciers as the “Birdmuda Triangle” for the number of birds that have disappeared during races there, though the triangle hasn’t been studied as intensely as Jersey Hill. Some say that radio signals from a nearby Royal Air Force satellite station jam the pigeons’ navigational equipment, but there is no evidence, as yet, that the birds can sense radio signals. For pigeons, certain areas just seem to present more navigational challenges than others.

Perhaps the all-time “most lost” award for a racing pigeon goes to Houdini, who disappeared during a 224-mile race in Britain only to show up five weeks later, in perfect health, on a rooftop in Panama City—5,200 miles away across the Atlantic. Houdini was thought to have hitched a ride on a ship headed for the Panama Canal. “I didn’t even know where Panama was,” Houdini’s owner reportedly said.

Even weirder, on one fateful day in 1998, more than 2,200 pigeons freakishly vanished during two separate races in Virginia and Pennsylvania on the same morning. Sixteen hundred of 1,800 pigeons went missing in one race and 600 of 700 birds never finished the other, amounting to an 85 percent loss rate. The story made national news. Nobody could say where the birds went or even offer a logical explanation. The weather was calm. It’s normal for a few pigeons to disappear during a 150-mile race, taken by peregrine falcons or guillotined by power lines, but the casualty rate is usually less than 5 percent; such a mass disappearance was nearly unprecedented. Organizers could only scratch their heads. None of the missing birds were ever found.

New technology might at least give us a clue to the mystery. Tiny global-positioning-system tags developed to be worn by pigeons in miniature backpacks, logging precise tracks of their movements, have suggested that pigeons maintain a hierarchical order in the air. The birds are fairly social, and when released, they usually form a tight flock and travel together back to the loft. Some birds tend to follow the decisions of others, so a few leaders end up guiding the pack, just like chickens in a coop. Social interaction probably helps less-experienced birds learn from older ones, a phenomenon largely ignored by scientists trying to explain the biology of homing behavior. This pecking order is usually a good system, but it isn’t perfect. In the case of the disappearing pigeons, perhaps a few leaders became confused—by infrasound, magnetic anomalies, or something else—and many others simply followed them over the horizon, never to return.

Even with all this instinctive know-how, homing pigeons must be intensively trained not to get lost. An owner will typically start by letting his birds fly around their loft, getting a

feel for the local area. Then the birds will go on a series of training flights, starting close to home and gradually working farther and farther away. It’s not magic. The birds have some innate ability, but they still need conditioning, just like human athletes, to be successful.

—

THIS TRAINING

is on prominent display at the biggest one-loft pigeon event in the world: the South African Million Dollar Pigeon Race. Each January, thousands of pigeon fanciers converge on the glittering Emperors Palace resort in Johannesburg to celebrate their birds’ powers of navigation—and a bit of high-roller betting.

At the Million Dollar, for one weekend every year, pigeons become bona fide celebrities, with an entourage to match. Queen Elizabeth II and Mike Tyson have both entered birds in the race. (Tyson once explained that after he quit boxing, keeping pigeons helped him stay sane, and he even starred in his own Animal Planet reality TV show about pigeon racing.) Part of the draw is the ridiculously high stakes. Breeders pay a flat $1,000 entry fee for the chance at $1.3 million in prizes, and winning birds, with names like Rubellos, East of Eden, and Four Starzzz Dream, are subsequently auctioned off for small fortunes as future breeders. In 2008, a particularly athletic pigeon named Birdy went for $102,000.

The race itself is straightforward. More than 3,500 pigeons are released simultaneously from a truck parked about 350 miles from the resort. The first bird to make it back to the resort wins. Pigeons are fitted with electronic chips, the same kind that marathon runners wear, to record their finishing times. The fastest birds usually complete the race in eight or ten

hours, depending on weather conditions, while thousands of human spectators watch live coverage on several jumbo screens in an indoor arena.

Everything about the race is extravagant, from its origins at Sun International’s Sun City Resort—an over-the-top casino in northern South Africa—to today’s incarnation at the Emperors Palace, complete with car giveaways for training runs and flashy auctions. The event is definitely not for the faint of heart or wallet. Elite pigeon racing has been increasingly infiltrated by Chinese magnates and northern European fanciers (a technical term) who can afford birds worth more than luxury cars, to the disgruntlement of some traditional breeders. At its highest level, the sport is all about numbers—dollars and seconds—and it’s easy to get mired in endless lists of rankings that form the bulk of the Million Dollar’s press releases and reports. But the magic remains. Anyone can understand a pigeon race, and everyone has wondered at some point about the birds that seem to carry a map and compass wherever they go.

The race organizers take training seriously because they don’t want prized birds to get lost during the main event, which is longer than most pigeon races. The birds are kept in state-of-the-art, quarantined facilities and pampered like movie stars. In the months before the race, they take part in twenty-seven different training flights, working up from 30 to 240 miles. Because some disappear on each of these shorter flights, owners may enter up to five reserve birds to rotate in. But even with the finest lodging and training, many of the best pigeons in the world still vanish after being dropped 350 miles from home in the remote bushveld of South Africa. No bird is perfect. On race day, the Million Dollar loss rate has varied between 30 and 70 percent.

—

THE LOST PIGEON IN FIELDS

belonged to Marty, who lived in Nampa, Idaho, 110 miles from where I found it. I got his phone number and called him up.

“Oh, yes,” he remembered, “she was one of our best birds, nice and speckled-looking.”

Marty, forty-four years old, builds manufactured homes during the day and races pigeons in his free time. He was introduced to the sport by his dad, who keeps an aviary with eighty to one hundred pigeons in his backyard; father and son spend nearly every weekend together to train and race their birds. They compete in an Idaho club with about twenty other pigeon owners, racing their birds against one another in half a dozen official events each spring and fall.

This particular pigeon, number 1961 (Marty doesn’t name his birds beyond their band numbers), had been released with 150 others on a training toss from Owyhee, Nevada, on April 7, in preparation for a race in that area a few days later. It should have traveled about 110 miles north to reach Marty’s loft in Nampa, Idaho, but had somehow ended up 130 miles west, in Fields, Oregon, a week later. Of all the birds released that day, including thirty of Marty’s pigeons, it was the only one not to make it home.

Marty wasn’t sure how it got lost, especially since its parents were two of his best breeders. Perhaps it had been frightened by a hawk—a pair of red-tailed hawks nesting in a big tree in his yard had lately been scaring the daylights out of his pigeons, though the hawks didn’t seem to go after them—and had then become separated from its group and veered off course. Marty had raised number 1961 with forty-eight other young pigeons the previous year and it had already proved its value in several

official races, the longest of which originated near Hoodoo, Oregon, about 275 miles west of its loft in Nampa. Some birds can race for five or six years, and this one should have been looking at a successful career.

“It’s unusual for a pigeon to go missing,” he told me. Two or three times a year, one of his birds ends up in the wrong loft—having followed others home to a different owner—and Marty gets a call from one of his friends. Only once every couple of years does someone call in with a legitimately lost pigeon. Pretty good, considering his birds take part in training flights every other day during racing season. Marty’s pigeons usually fly directly home without stopping, but he has seen a few arrive weeks later, so it was still possible that this one could get its bearings.

When I asked how his birds managed to find their way home, Marty didn’t mention magnetic fields or specialized neurons. Over decades of tending his flock an hour or two each day, he has come to know them as individuals. “Pigeons are real smart,” he replied simply. “People don’t realize it, but these birds are very intelligent.”

spontaneous order

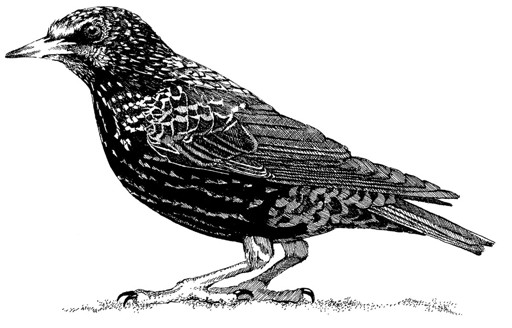

THE CURIOUS MAGNETISM OF STARLING FLOCKS

I

n early November 2011, my inbox suddenly exploded with e-mails from friends, relatives, and casual acquaintances, each one linking to the same two-minute online video clip, titled “Murmuration.” Unsure what to expect, I clicked on the link.

For the first twenty seconds, the video shows two young women canoeing on a damp evening in Ireland, filming each other with a shaky hand from inside the boat. You begin to wonder what the point is. Then, at 0:23, the view zooms up and out, New Age music fades in, and as the camera adjusts its exposure, you realize that the Irish dusk is full of flying birds—a

lot

of birds, silhouetted in impossibly coordinated patterns from one horizon to the other, blotting out the clouds with their thousands. For the next eighty-one seconds, the birds perform an intricate display of aerial formation, bunching and flattening like a throng of baitfish under attack; you can even hear the whoosh when they make a low, strafing pass overhead. Then the birds fly away and it’s over.

The two women, film students Sophie Windsor Clive and Liberty Smith, were working on a graduation project for the London College of Communication when they decided to take their canoe trip. They had no idea that an enormous flock of European starlings habitually roosts in the area where they planned to visit some ruins on a small island. When the women posted their impromptu starling footage online, hardly anyone noticed at first—it averaged ten views per day for the first week. Then

The Huffington Post

linked to it and the video suddenly went viral, garnering 1.05 million views in twenty-four hours.

Over the next few months, more than 10 million people would see it.

If you’ve ever watched a flock of starlings (poetically called a murmuration, just as crows make a murder and owls a parliament) go to roost, you know why the video mesmerized so many distracted Web surfers. Starlings habitually gather at night, sometimes by the hundreds of thousands in late summer, and in the evening, just before they settle into bed, the birds collectively patrol the airspace above their sleeping quarters, sometimes for half an hour or more. Few birds in the world form such dense, tight flocks. Why starlings do it is an open question. Burning extra energy before drifting off? Guiding incoming stragglers? Keeping an eye out for predators? But there is no dispute that the spectacle is awe-inspiring. The aerial displays resemble dense smoke caught in the grip of an invisible tornado. It’s hard not to wonder how the birds stay in such a rapidly changing formation and manage not to bump into one another.

The aesthetics alone are inspiring. New York–based photographer Richard Barnes, best known for his starkly artistic portraits of Unabomber Ted Kaczynski’s cabin, released a captivating collection of black-and-white images of starling flocks over Rome in 2005. His photos are carefully framed against urban horizons. Some are simply beautiful, others sinister and Hitchcockian, but all are somehow magnetic (more on that later). In a statement accompanying Barnes’s images, author Jonathan Rosen observes, “Part of the fascination of the starlings is the way they seem to be inscribing some sort of language in the air, if only we could read it.”