The Thing with Feathers (7 page)

Read The Thing with Feathers Online

Authors: Noah Strycker

Cavagna’s team wanted to describe starling flocks with pure physics. They measured the velocities of birds at different positions within a flock and found, as you’d expect, that birds behaved more like those close to them than they did like those farther away. When Cavagna compared these correlation lengths between flocks of different sizes, though, he discovered that they scaled perfectly with the size of the group—birds behaved similarly across longer distances in bigger flocks. He called this a scale-free correlation, and pointed out that this was a feature of critical systems, poised at a tipping point.

Water becomes a critical system when it freezes, and also when it boils. Avalanches are said to reach a critical point at the moment when they break free. Magnets become critical when they spontaneously align from disorder. Perhaps, Cavagna thought, starlings represent a system that forms flocks at a critical point.

Then the team analyzed flight directions within a starling flock. They found a model that correctly predicted order within the flock, and proceeded to demonstrate, in a dense, eighteen-page paper, that it was mathematically equivalent to a well-known model of magnetic systems at critical points called the Heisenberg model, which uses quantum mechanics to describe magnetic orientations. When iron, say, is cooled below a certain

temperature, it spontaneously magnetizes. Electrons within the material align their spins below that critical point. Spontaneous magnetism, Cavagna and other physicists argued, was happening in the alignment of flight directions within a flock of starlings. Equations of magnets, it turns out, can describe a starling flock better than biology can.

—

CAN EQUATIONS REALLY EXPLAIN

how starlings perform coordinated flight? Does physics underlie even the most spontaneous, beautiful displays of life on earth? The answer depends, in a sense, on whether you believe math is discovered or invented; whether it’s a pervasive force, guiding every action in this universe, or whether logic is imposed by the human brain. History’s most ardent philosophers have agonized over the issue, and they are still arguing.

I like to think that life defies physics, and that the beauty of a cartwheeling flock of starlings originates with the birds themselves rather than in a universal law—in the same way that a Renaissance masterpiece may follow specific rules but still takes a real master to produce. As emergence writer Peter Corning pointed out, knowing the rules doesn’t always bring a solution any closer.

Andrea Cavagna believes that physics can help us make sense of the natural world, even in ways that may not seem obvious, and his team certainly documented some fascinating observations about flocking behavior in birds. But millions of online viewers reached the same conclusion by instinct and genuine fascination. However you look at it, a murmuration of starlings is absolutely magnetic.

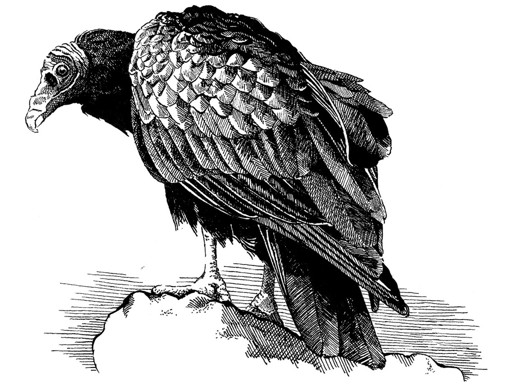

the buzzard’s nostril

SNIFFING OUT A TURKEY VULTURE’S TALENTS

O

ne day in high school, I told my parents I wanted to photograph vultures.

“Great,” they said. “But how will you get close enough?”

“By putting a dead deer in our yard.”

I’d been inspired by an episode of David Attenborough’s

The Life of Birds

documentary, the one where the British filmmaker ventures into a Trinidad rainforest carrying a fist-sized hunk of rotting beef. With great flourish, Attenborough hides the meat under a layer of wet leaves on the dark jungle floor and then backs away, muttering lilting phrases such as: “Their beaks are quite adequate for tearing off strips of flesh.” Within forty-five minutes, a turkey vulture appears out of nowhere and uncovers the delicacy—quite a trick, for filmmaker and scavenger alike.

If Sir David could lure a vulture with a funky old steak, then how many vultures might a whole deer carcass attract? Just imagine how smelly

that

would be.

My parents were used to this sort of scheme. They weren’t sure how or why their son had become so obsessed with birds, but, considering the various other possible vices, had resigned to embrace this one. Their only stipulation was that the dead animal be placed far enough from the house not to stink up the kitchen.

I’d recently acquired my driver’s license and had been cruising the local birding hot spots in an old white Volvo sedan. The car was built like a tank and boasted a two-body trunk—or at least, to my discerning eye, a trunk roomy enough for one average deer carcass. I stocked the trunk with gloves and Hefty bags, and began scouring the countryside for flattened deer.

As it happens, a fine roadkill is hard to locate when you really want one. I found myself in competition with Department of Transportation crews assigned to remove carcasses from the state highways, a local wolf sanctuary with permission to collect cadavers for its carnivores, and the odd redneck with a big freezer. Still, there was reason for optimism. Insurance companies estimate that 1.5 million deer collide with cars annually in the United States, and of these nearly 90 percent perish on impact. A corpse would turn up.

Meanwhile, I took a fresh interest in the vultures around me. The state of Oregon in summer abounds with turkey vultures, usually wafting lazily overhead with raised wing tips, rocking slightly while circling a thermal column of rising air. They’re stout-looking birds up close, with a dark, smoky cloak of mahogany and black plumage supporting a bare-skinned, creepy pinkish head. The birds began to fascinate me. And the more time I spent stalking roadkill and vultures alike, the more I realized that these scavengers—and the people who have studied them—are far wackier than even I could have imagined.

—

WHETHER BIRDS POSSESS

a sense of smell has been debated for centuries. There’s no doubt that most are visually oriented, like us, and experts have historically downplayed any whiff of avian smelling ability. But traditional views are beginning to soften, and turkey vultures are proving to be one of the biggest exceptions to the rule.

Vultures have long been recognized for their special talents at uncovering carrion, their favorite food. Aristotle mused on the ability of vultures—probably European vultures, unrelated to vultures in the New World—to home in on dead animals,

suggesting that they must follow their noses. By the early 1800s, most people believed that vultures find their food by sniffing it out. It was an easy assumption, as the carcasses of dead animals assault even our own mediocre noses, but one worth challenging.

In 1826, John James Audubon reached his own conclusions after experimenting with both turkey and black vultures in the eastern United States. The eminent ornithologist hid hunks of rotten meat beneath pieces of paper and placed them near caged vultures. The vultures seemed not to notice. Then he left a deer stuffed with foam, not meat, in an open field. The vultures investigated it. Finally, he hid a rotting deer corpse under some brush, out of sight of the sky. The vultures never found it. Audubon, at odds with accepted wisdom, decided that the birds did not discover food by smell, but by sight alone. His paper, “Account of the Habits of the Turkey Buzzard, Particularly with the View of Exploding the Opinion Generally Entertained of Its Extraordinary Power of Smelling,” was met with widespread ridicule. Seven years later, in publications such as London’s

Magazine of Natural History

, the discussion had dissolved into personal attacks on the man himself—who at the time had declared his ambition to paint every bird in North America.

In desperation, Audubon wrote pleading letters to his good friend John Bachman, an American naturalist for whom a sparrow and warbler are now named. Bachman was sympathetic; an excellent field man himself, he had strong views about armchair critics. “It has always appeared to me an act of injustice to condemn any man for expressing an opinion on subjects of Natural History,” Bachman later wrote, “merely because he had arrived at different conclusions from those who had lived before him.”

Bachman agreed to try his own vulture experiment. He figured the question should be simple to resolve. “No one who will read Mr. Audubon’s paper,” he said, “can deny that if he intended to deceive the world, he certainly chose a subject where detection was easy and certain.”

Not everyone disputed Audubon’s vulture study, though. A young Charles Darwin, in his travel memoir,

The Voyage of the Beagle

, described his experiences with South American Andean condors about ten years later. “Remembering the experiments of M. Audubon, on the little smelling powers of carrion-hawks, I tried the following experiment,” Darwin wrote, describing how he had once, in Chile, tethered several condors in a row to the base of a wall, then walked back and forth in front of them while carrying rotten meat in a paper wrapper. The birds took no notice until he pushed the putrid package against the beak of an old male condor; at that point, the bird tore off the paper and all the condors suddenly began to struggle against their tethers. “Under the same circumstances, it would have been quite impossible to have deceived a dog,” wrote Darwin, who concluded that the condors couldn’t smell their food.

Rather than generalize his result to all vultures, Darwin was circumspect. He had heard of vultures collecting on rooftops in the West Indies on houses whose human residents had died without discovery—surely a sign that the birds had sniffed the odor of decay. He also knew of an anatomic study on the large olfactory bulb of turkey vultures and the results of several other field experiments. His conclusion was that “the evidence in favor of and against the acute smelling powers of carrion-vultures is singularly balanced.” Though Darwin was in his mid-twenties when he experimented with his condors, and just thirty when he published

The Voyage of the Beagle

, his analytic mind was already apparent; in another twenty years, he

would pen

On the Origin of Species

and change the world’s views on life itself.

At exactly the same time that Darwin was playing with condors in South America, in the winter of 1833–1834, John Bachman was conducting a series of vulture experiments in South Carolina to resolve the smelly argument once and for all.

First, Bachman set out to disprove an odd myth, circulated in newspapers at the time, that a vulture with a punctured eye would tuck its head under its wing and restore its own sight within a few moments. In Bachman’s experiment (which wouldn’t go over so well today), a captive turkey vulture’s eyes were pierced and it predictably went blind. Recognizing an opportunity, Bachman then tested whether the blinded vulture could detect rotten meat by smell alone. When he dangled the rancid flesh of a hare within an inch of the vulture’s beak, the bird made no move; the only way to get the vulture to eat was by putting food directly in its mouth. The poor vulture died twenty-four days after its eyes had been poked out, and Bachman was convinced that his experiment had confirmed Audubon’s earlier results.

He didn’t stop there. Bachman next gathered up carcasses of a hare, a pheasant, and a kestrel, and left them in a heap in his garden along with a wheelbarrow load of slaughter-pen offal. He covered everything under a raised frame and camouflaged it with brush so that the pile was invisible from above but open to the air at ground level. Although the stench of the “dainty mess” became nearly unbearable after twenty-five days, the many vultures that passed overhead never investigated Bachman’s garden. Only the neighborhood dogs raided the offering, and Bachman again concluded that the vultures couldn’t smell it. A few manipulations seemed to confirm his conclusion: When he uncovered the pile, the vultures arrived. When he hid

the pile under thin canvas and scattered a few pieces on top, the vultures ate the obvious food but didn’t go for the goodies below. When he tore a small hole in the canvas to show what was underneath, the vultures dug in with gusto.

Finally, the enterprising Bachman devised a more artistic test. On a new canvas, he painted a life-sized depiction of a dead sheep, skinned and cut open with its entrails showing. When the painting was finished, he set it outside to see what the vultures would do.

“No sooner was this picture placed on the ground, than the Vultures observed it, alighted near, walked over it, and some of them commenced tugging at the painting. They seemed much disappointed and surprised, and after having satisfied their curiosity, flew away,” he wrote in a scientific paper describing the vulture studies, barely disguising his glee. Bachman repeated his painted experiment more than fifty times with the same result. As his pièce de résistance, he set the painting within ten feet of the heap of camouflaged offal in his garden. The vultures investigated the picture as usual, but departed without discovering the real treat right under their noses.

As far as Bachman was concerned, Audubon had been vindicated: Vultures find their food by sight, not smell. He wouldn’t say that vultures

can’t

smell, just that they don’t use their noses the way dogs and many other animals do in tracking down a meal. When he published his results, nobody could dispute the findings.