Farm Boys: Lives of Gay Men from the Rural Midwest

Read Farm Boys: Lives of Gay Men from the Rural Midwest Online

Authors: Unknown

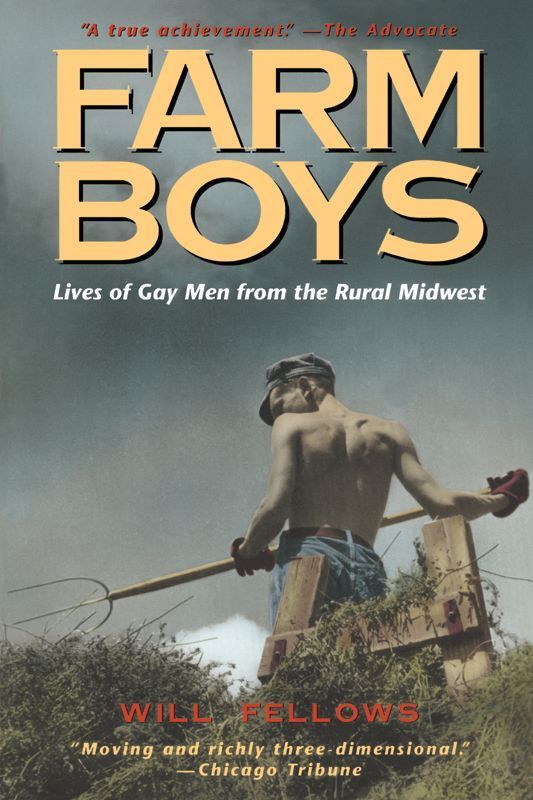

FARM BOYS

Lives of Gay Men from

the Rural Midwest

Collected and edited by

Will Fellows

THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN PRESS

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

Copyright © 1966, 1998

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embeddded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fellows, Will.

Farm boys: lives of gay men from the rural Midwest / Will Fellows.

352 pp. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-299-15080-1 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 0-299-15084-4 (paper: alk. paper)

1. Gay men—Middle West—Case studies. 2. Farmers—

Middle. West—Case studies. I. Title.

HQ76.2.U52M534 1996

305.38’9664–dc20 96-6058

ISBN 978-0-299-15083-9 (ebook)

Whatever actually happens to a man

is wonderfully trivial and insignificant,

—even to death itself, I imagine.

—

Henry David Thoreau

How These Stories Were Discovered

PART 1:

Coming of Age Before the Mid-1960s

PART 2:

Coming of Age Between the Mid-1960s and Mid-1970s

PART 3:

Coming of Age Between the Mid-1970s and Mid-1980s

This work is about the lives of gay men who grew up on farms in the mid-western United States during the twentieth century. I have done this work in the interest of promoting a fuller appreciation of the varied origins of, and perspectives within, the population of gay men in the U.S. I hope that the reader will find these plain-spoken narratives to be engaging and illuminating in their candor, insight, and sense of humor. It is also my hope that this work will be of value to individuals who are exploring issues related to sexual and gender identity.

These men describe how they perceived and responded to a variety of conditions that existed in many of the farm communities and families of their boyhoods: rigid gender roles, social isolation, ethnic homogeneity, suspicion of the unfamiliar, racism, religious conservatism, sexual prudishness, and limited access to information. While none of these conditions is unique to farm culture, they operate in a distinctive synergy in that setting.

They also have a lasting impact. More than just boyhood memories, these stories describe the long-term influences that many of these men believe their upbringings have had on the course and character of their lives. How has their farming heritage influenced their choices and identities as gay men? How do they see themselves in relation to gay men from urban or suburban backgrounds? How do they fit into their local gay communities? Inherent in these stories are the very different experiences and perspectives of men who came of age in earlier decades of this century and those who came of age in more recent decades—especially in the 1970s and 1980s.

In preparing these narratives from interviews, I have seen myself as something of a midwife, listening to men who had something to say and delivering their experiences and perspectives to the reader in their own distinct voices. If I had believed that soliciting contributions from professional writers would have yielded as diverse a cross-section of gay “farm boys,” I

might have chosen to edit their writings and organize them in a collection. In the interest of presenting a greater range of largely unheard voices, I have collaborated with my own group of subjects to shape autobiographical narratives from their interview transcripts. Because very few of these men were writers, it is unlikely that most of these stories would have been told unless someone had come along with a litany of questions and a tape recorder.

Despite my efforts to let these men’s words speak for them, my own background has no doubt influenced the ways in which I have gone about asking them to talk about their lives, as well as the ways in which I have understood and edited their words. I was born in 1957 and grew up on a Wisconsin dairy farm that had been in the family for more than a century. Apart from the inevitable jolts and angst of growing up, my childhood was one of naivety, safety, stability, and freedom. My parents expected me to do a certain amount of housework and farmwork, but my childhood was not consumed by endless toil or rigid expectations.

Living five miles from town, with few neighbor kids my age, I played mostly with my two younger sisters and weathered typical fraternal harassment from my older brother. I pleased my teachers at public school and Baptist church in town, played with my toy printing press, collected coins, and completed 4-H projects in drama, woodworking, and nature conservation. My feelings of rootedness and belonging were strengthened as I researched my father’s family history, tracing our tenure on the farm back to its beginnings in the 1850s.

I chose to spend a lot of time with my paternal grandmother who lived in the old farmhouse next door, surrounded by her beloved antiques and books and other fine things. For several years in my teens, I operated a small antique shop in an old poultry shed that my father helped me refurbish. Through high school I was essentially a sexually naive loner, feeling no great inclination to date girls or to fool around with boys. I edited the school newspaper, wrote for a local weekly paper, and spent a summer as a foreign exchange student (feeling homesick much of the time). Coming out to myself and my family between eighteen and twenty-one years of age was relatively free of pain.

My life since leaving the farm for college has been largely urban, mid-western, and variously fulfilling. There is much I have come to like about city life, but I have tended to feel like an outsider in the gay communities of the cities in which I have lived. And I have had similar feelings in relation to the larger gay “community” in the United States, as represented in popular gay-themed books, periodicals, and movies. In an effort to gain a better understanding of what I bring to the experience of being gay as a result, perhaps, of my farm upbringing, I have looked for books telling

about my kind of childhood. The body of literature that examines the lives of gay men has expanded greatly in recent years and has enriched my life in many ways, but it neglects the experiences and perspectives of gay men who grew up in farm families. Urban or suburban experiences are central to the lives of most gay men, but they constitute only part of the story.

It is not uncommon for gay men who grew up on farms to regard their rural roots as irrelevant or embarrassing. Those attitudes tend to be reinforced by the popular gay press, in which the most common representations of the rural childhood experience include a variety of farm-boy stereotypes, fantasies, and romanticized, back-to-nature images. Charles Silverstein described some of these popular perceptions in his 1981 book,

Man to Man: Gay Couples in America.

1

City gays imagine the boys on the farm as somehow more wholesome than themselves. Soaking up the sun while pitching a bale of hay, their bodies taking on a bronze glow, these promising young men develop tight muscles from manual labor and hardiness; the lines in their faces and the callouses on their hands are the results of wind, rain, and the warming sun. In short, they are pictured as country bumpkins with rosy cheeks, ready to be plucked if they venture into the big city (p. 241).

In our interview, Clark Williams described his own experience with these stereotypical perceptions.

A lot of men idealize the naive, good-looking, tanned farm boy. “Wouldn’t you love to go to bed with him? Wouldn’t you love to have him, to take him down?” I’ve had some guys take that kind of approach with me. I’m supposed to be wide-eyed, naive, less intelligent, and in denial about who I am. They’ll ask me, “Are you married? Do you have a girlfriend?”

The life stories presented here are not primarily those of gay men who stayed in the rural farming communities where they grew up. A large majority of these men have left farming and rural communities, choosing to live in or near relatively large midwestern cities. Richard Kilmer was succinct in assessing his own choice to leave.

If I had stayed on the farm, I would have never dealt with being gay. I would have probably gotten married and had sex with men on the side. I think a lot of gays don’t leave the farm, so there’s probably a lot of people out there who are doing that. So many people there are alcoholics, and I think that’s what a lot of gays gravitate towards, to kind of deaden their feelings.

Barney Dews grew up on a farm in East Texas in the 1960s and 1970s, and was living in Minneapolis at the time of our interview. Although he is not a midwesterner, his description of “a centrifugal force that slings gay

people as far away as possible, to escape,” is relevant to many of these men’s experiences. It seems likely that by having uprooted and distanced themselves from the families and communities of their childhoods, these men were able to look at their lives with more insight and clarity than would have been possible had they stayed. As these stories reveal, their views of growing up range widely, from bitter to beatific.

1.

Silverstein, Charles. 1981.

Man to Man: Gay Couples in America.

New York: Quill.

The idea for this project was conceived as the result of conversation over dinner with my friend Karl Wolter. Clarification and refinement of this original idea were enhanced by conversations with many others, especially Doug Baudei, John Berg, Fran^231;oise Cr^233;lerot, Joanne Csete, Carlos Dews, Kim Karcher, Ming Liang Kwok, Lon Mickelsen, Sarah Newport, Brian Powers, Larry Reed, Julia Salomon, Martin Scherz, Jack Siebert, and Jane Vanderbosch. I thank all of my friends and family members for their contributions to making things happen as well as they did.

Early interest in the Gay Farm Boys Project was shown by The New Harvest Foundation of Madison, Wisconsin, the Cream City Foundation of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and The Madison Community United. I am indebted to them, as I am to my friend Joanne Csete, for generous and encouraging financial support.

Bonnie Denmark Friedman was a superb transcriber and Jeff Kopseng has been a dream of an illustrator. This work has been greatly improved by the efforts of Rosalie M. Robertson and Raphael Kadushin at the University of Wisconsin Press, and by the encouraging editorial advice of David Bergman, David Roman, and Reed Woodhouse. I thank Robert Peters for permission to use excerpts from his book,

Crunching Gravel: A Wisconsin Boyhood in the Thirties

(University of Wisconsin Press, 1993). I am grateful to all of the men who agreed to be interviewed, including those whose stories I have not been able to include in this volume.