The Tanners (4 page)

Authors: Robert Walser

The first prose work I read by Robert Walser was his piece on Kleist in

Thun, where he talks of the torment of someone despairing himself and his craft, and

of the intoxicating beauty of the surrounding landscape. "Kleist sits on a

churchyard wall. Everything is damp, yet also sultry. He opens his shirt, to breathe

freely. Below him lies the lake, as if it had been hurled down by the great hand of

a god, incandescent with shades of yellow and red […] The Alps have come to life and

dip with fabulous gestures their foreheads into the water." Time and again I have

immersed myself in the few pages of this story and, taking it as a starting point,

have undertaken now shorter, now longer excursions into the rest of Walser's work.

Among my early encounters with Walser I count the discovery I made, in an antiquarian

bookshop in Machest in the second half of the 1960s––inserted in a copy of

Bächtold's three-volume biography of Gottfried Keller which had almost certainly

belonged to a German-Jewish refugee––of an attractive sepia photograph depicting the

house on the island in the Aare, completely surround by shrubs and trees, in which

Kleist worked on his drama of madness

Die Familie Ghonorez

before he,

himself sick, had to commit himself to the care of Dr. Wyttenbach in Berne.

Since then I have slowly learned to grasp how everything is connected

across space and time, the life of Prussian writer Kleist with that of a Swiss

author who claims to have worked as a clerk in a brewery in Thun, the echo of a

pistol shot across the Wannsee with the view from a window of the Herisau asylum,

Walser's long walks with my own travels, dates of birth with dates of death,

happiness with misfortune, natural history and the history of our industries, that

of

Heimat

with that of exile. On all these paths Walser has been my

constant companion. I only need to look up for a moment in my daily work to see him

standing somewhere, a little apart, the unmistakable figure of the solitary walker

just pausing to take in the surroundings. And sometimes I imagine that I see with

his eyes the bright

Seeland

and within this land of lakes the lake like a

shimmering island, and in this lake-island another island, the Île Saint-Pierre

"shining in the bright morning haze, floating in a sea of pale trembling light."

Returning home then in the evening we look out, from the lakeside path suffused by

mournful rain, at the boating enthusiasts out on the lake "in boats or skiffs with

umbrellas opened above their heads," a sight which allows us to imagine that we are

"in China or Japan or some other dream-like poetical land." As Mächler reminds us,

Walser really did consider for a while the possibility of traveling, or even

emigrating, overseas. According to his brother, he once even had a check in his

pocket from Bruno Cassirer, good for several months' travel to India. It is not

difficult to imagine him hidden in a green leafy picture by Henri Rousseau, with

tigers and elephants, on the veranda of a hotel by the sea while the monsoon pours

down outside, or in front of a resplendent tent in the foothills of the Himalayas,

which––as Walser once wrote of the Alps––resemble nothing so much as a snow-white

fur boa. In fact he almost got as far as Samoa, since Walter Rathenau, whom––if we

may believe

The Robber

on this point––he had met one day, quite by chance,

in the midst of an incessant stream of people and traffic on the Potsdamer Platz in

Berlin, apparently wanted to find him a not-too-taxing position in the colonial

administration on the island known to the Germans as the "Pearl of the South Seas."

We do not know why Walser turned down this in many ways tempting offer. Let us

simply assume that it is because, among the first German South Sea discoverers and

explorers, there was a certain gentleman called Otto von Kotzebue, against whom

Walser was just as irrevocably prejudiced as he was against the playwright of the

same name, whom he called a narrow-minded philistine, claiming he had a too-long

nose, bulging eyes and no neck, and that his whole head was shrunk into and hidden

by a grotesque and enormous collar. Kotzebue had, so Walser continues, written a

large number of come die which enjoyed runaway box-office success at a time when

Kleist was in despair, and bequeathed a whole series of these massive, collected,

printed volumes, coxed and boxed and bound in calfskin, to a posterity which would

blench with shame were it ever to read them. The risk of being reminded, in the

midst of a South Sea idyll, of this literary opportunist, one of the heroes of the

German intellectual scene, as he dismissively calls him, was probably just too high.

In any case, Walser didn't care much for travel and––apart from Germany––never

actually went anywhere to speak of. He never saw the city of Paris, which he dreams

of even from the asylum at Waldau. On the other hand, the Untergasse in Biel could

seem to him like a street in Jerusalem "along which the Saviour and deliverer of the

world modestly rides in." Instead he criss-crossed the country on foot, often on

nocturnal marches with the moon shining a white track before him. In the autumn of

1925, for example, he journeyed on foot from Berne to Geneva, following for quite

a

long stretch the old pilgrim route to Santiago da Compostela. He does not tell us

much about this trip, other than that in Fribourg––I can see him entering that city

across the incredibly high bridge over the Sarine––he purchased some socks; paid his

respects to a number of hostelries; whispered sweet nothings to a waitress from the

Jura; gave a boy almonds; strolling around in the dark doffed his hat to the Roussea

monument on the island in the Rhône; and, crossing the bridges by the lake,

experienced a feeling of light-heartedness. Such and similar matters are set down

for us in the most economical manner on a couple of pages. Of the walk itself, we

learn nothing and nothing about what he may have pondered in his mind as he walked.

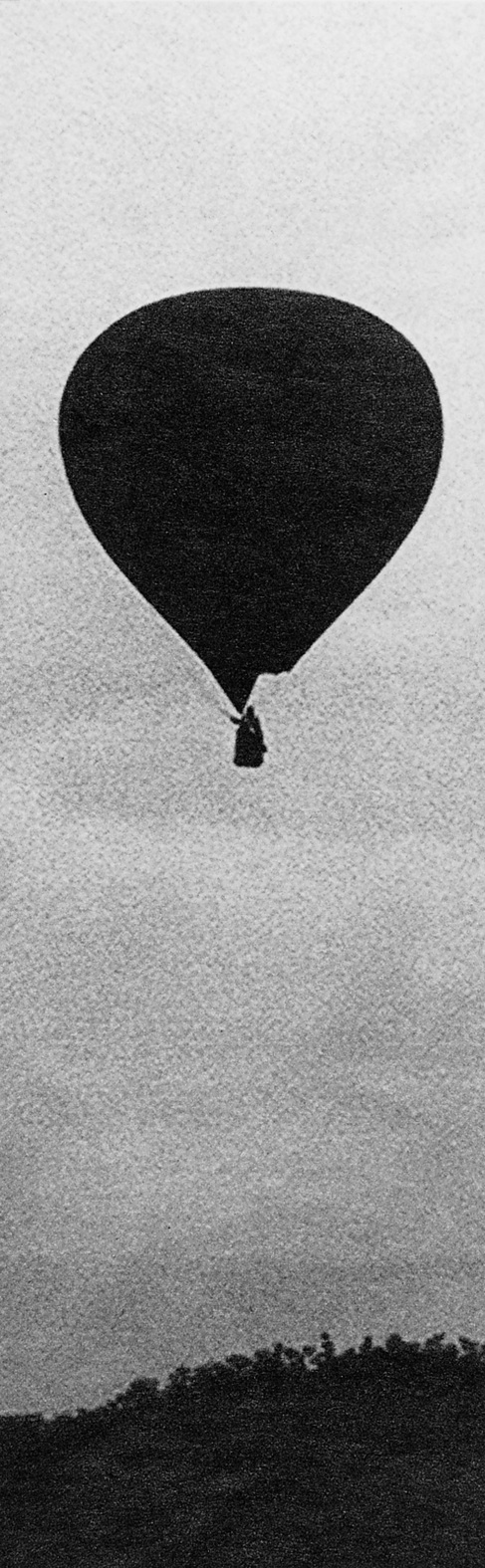

The only occasion on which I see the traveller Robert Walser freed from the burden

of himself is during the balloon journey he undertook, during his Berlin years, from

Bitterfield––the artificial lights of whose factories were just beginning to

glimmer––to the Baltic coast. "Three people, the captain, a gentleman, and a young

girl, climb into the basket, the anchoring cords are loosed, and the strange house

flies, slowly, as if it had first to ponder something, upward…. The beautiful

moonlit night seems to gather the splendid balloon into invisible arms, gently and

quietly the roundish flying body ascend and … hardly so that one might notice,

subtle winds propel it northward." Far below can be seen church spires, village

schools, farmyards, a ghostly train whistle by, the wonderfully illuminated course

of the Elbe in all its colors.

"Remarkably white, polished-looking plains alternate with gardens and

small wildernesses of bush. One peers down into regions where one's feet would

never, never have trod, because in certain regions, indeed in most, one has no

purpose whatever. How big and unknown to us the earth is!" Robert Walser was, I

think, born for just such a silent journey through the air. In all his prose works

he always seeks to rise above the heaviness of earthly existence, wanting to float

away softly and silently into a higher, freer realm. The sketch about the balloon

journey over a sleeping nocturnal Germany is only one example, one which for me is

associated with Nabokov's memory of one of his favorite books from his childhood.

In

his picture-book series, the black Golliwog and his friends––one of whom is a kind

of dwarf or Lilliputian person––survive a number of adventures, end up far away from

home and are even captured by cannibals. And then there is a scene where an airship

is made of "yards and yard of yellow silk … and an additional tiny balloon […]

provided for the sole use of the fortunate Midget. At the immense altitude," writes

Nabokov, "to which the ship reached, the aeronauts huddled together for warmth while

the lost little soloist, still the object of my intense envy notwithstanding his

plight, drifted into an abyss of frost and stars––alone."

3

––TRANSLATED BY JO CATLING

1.

Walter Benjamin.

"Robert Walser," in

Selected Writings: vol 2. 1927-34

(Harvard).

2.

Vladimir Nabokov,

Nikolai

Gogol

(New Directions).

3.

Vladimir Nabokov,

Speak,

Memory

(Random House).

The Tanners

–1–

One morning a young, boyish man walked into a bookshop and asked to

be introduced to the proprietor. His request was granted. The bookseller, an

old

man of quite venerable appearance, gave a sharp glance at the one standing

rather shyly before him and instructed him to speak. “I want to become a

bookseller,” said the youthful novice, “I yearn to become one, and I don’t know

what might prevent me from carrying out my intentions. I’ve always imagined the

trade in books must be an enchanting activity, and I cannot understand why I

should still be forced to pine away outside of this fine, lovely occupation.

For

you see, sir, standing here before you, I find myself extraordinarily well

suited for selling books in your shop, and selling as many as you could possibly

wish me to. I’m a born salesman: chivalrous, fleet-footed, courteous,

quick, brusque, decisive, calculating, attentive, honest—and yet not so

foolishly honest as I might appear. I am capable of lowering prices when a poor

devil of a student is standing before me, and of elevating them as a favor to

those wealthy individuals who, as I can’t help noticing, sometimes don’t know

what to do with all their money. Although I’m still young, I believe myself in

possession of a certain knowledge of human nature—besides which, I love people,

of every variety, so I would never employ my insight into their characters in

the service of swindling—and I am equally determined never to harm your esteemed

business through any exaggerated solicitousness toward certain underfinanced

poor devils. In a word: My love of humankind will be agreeably balanced with

mercantile rationality on the scales of salesmanship, a rationality which in

fact bears equal weight and appears to me just as necessary for life as a soul

filled with love: I shall practice a most lovely moderation, please be assured

of this in advance—”

The bookseller was looking at the young man attentively and with

astonishment. He appeared to be having trouble deciding whether or not his

interlocutor, with this pretty speech, was making a good impression on him. He

wasn’t quite sure how to judge and, finding this circumstance rather confusing,

he gently inquired in his self-consciousness: “Is it possible, young

man, to make inquiries about your person in suitable places?” The one so

addressed responded: “Suitable places? I’m not sure what you mean by suitable.

To me, the most appropriate thing would be if you didn’t make inquiries at all!

Whom would you ask, and what purpose could it serve? You’d find yourself regaled

with all sorts of information regarding my person, but would any of it succeed

in reassuring you? What would you know about me if, for example, someone were

to

tell you that I came from a very good family, that my father was a man worthy

of

respect, that my brothers were industrious hopeful individuals, and that I

myself was quite serviceable, if a bit flighty, but certainly not without

grounds for hope, in fact that it was clearly all right to trust me a little,

and so forth? You still wouldn’t know me at all, and most certainly wouldn’t

have the slightest reason to hire me now as a salesclerk in your shop with any

greater peace of mind. No, sir, as a rule, inquiries aren’t worth a fig, and

if

I might make so bold as to venture to offer you, as an esteemed older gentleman,

a piece of advice, I would heartily advise against making any at all—for I know

that if I were suited to deceive you and inclined to cheat the hopes you place

in me on the basis of the information you’d gather, I would be doing so in even

greater measure the more favorably the aforementioned inquiries turned out,

inquiries that would then prove to be mendacious, if they spoke well of me. No,

esteemed sir, if you think you might have a use for me, I ask that you display

a

bit more courage than most of the other business owners I’ve previously

encountered and simply engage me on the basis of the impression I am making on

you now. Besides, to be perfectly truthful, any inquiries concerning my person

you might make will only result in your hearing bad reports.”

“Indeed? And why is that?”

“I didn’t last long,” the young man continued, “in any of the places

I’ve worked at thus far, for I found it disagreeable to let my young powers go

stale in the narrow stuffy confines of copyists’ offices, even if these offices

were considered by all to be the most elegant in the world—those found in banks

for example. To this day, I haven’t yet been sent packing by anyone at all but

rather have always left on the strength of my own desire to leave, abandoning

jobs and positions that no doubt carried promises of careers and the devil knows

what else, but which would have been the death of me had I remained in them.

No

matter where it was I’d been working, my departure was, as a rule, lamented,

but

nonetheless after my decision was found regrettable and a dire future was

prophesied for me, my employers always had the decency to wish me luck with my

future endeavors. With you, sir, in your bookshop (and here the young man’s

voice grew suddenly confiding), I will surely be able to last for years and

years. And in any case, many things speak in favor of your giving me a try.”

The

bookseller said: “Your candor pleases me, I shall let you work in my shop for

a

one-week trial period. If you perform well and seem inclined to stay,

then we can discuss it further.” With these words, which signaled the young

man’s dismissal, the old man at the same time rang an electric bell, whereupon,

as if arriving on the gusts of a strong wind, a small, elderly, bespectacled

man

appeared.

“Give this young man something to do!”

The spectacles nodded. With this, Simon became an assistant

bookseller. Simon—for that was his name.

At around this same time, Professor Klaus, a brother of Simon’s who

lived in a historic capital where he’d made a name for himself, had begun to

worry about his younger brother’s behavior. A good, quiet, dutiful person, he

would dearly have loved to see his brothers find the firm

respect-commanding ground beneath their feet in life that he, the

eldest, had. But this was so utterly not the case, at least till now, in fact

it

was so very much the opposite, that Professor Klaus began to reproach himself

in

his heart. He told himself, for example: “I should have been a person who would

long since have had every opportunity to lead my brothers to the right path.

Until now I’ve failed to do so. How could I have neglected these duties, etc.”

Dr. Klaus knew thousands of duties, small and large, and sometimes it seemed

as

if he were longing to have even more of them. He was one of those people who

feel so compelled to fulfill duties that they go plunging into great collapsing

edifices constructed entirely of disagreeable duties simply out of the fear that

some secret, inconspicuous duty might somehow elude them. They cause themselves

to experience many a troubled hour because of these unfulfilled duties—never

stopping to consider how one duty always piles a second one upon the person

undertaking the first—and they believe they’ve already fulfilled something like

a duty just by being made anxious and uneasy by any dark inkling of its

presence. They meddle in many an affair that—if they’d stop to think about it

in

a less anxious way—hasn’t a blessed thing to do with them, and they wish to see

others as worry-laden as themselves. They tend to cast envious glances

upon naïve unencumbered people, and then criticize them for being frivolous

characters since they move through life so gracefully, their heads held so

easily aloft. Dr. Klaus often forced himself to entertain a certain small modest

sensation of insouciance, but always he would return again to his gray dreary

duties, in the thrall of which he languished as in a dark prison. Perhaps, back

when he was still young, he’d once felt a desire to stop, but he’d lacked the

strength to leave undone something that resembled a nagging duty and couldn’t

just walk past it with a dismissive smile. Dismissive? Oh, he never dismissed

anything at all! Attempting this—or so it seemed to him—would have split him

in

twain from bottom to top; he’d have been incapable of avoiding painful

recollections of what he’d cast aside and dismissed. He never dismissed or

discarded anything at all, and he was wasting his young life analyzing and

examining things utterly unworthy of examination, study, attention or love. Thus

he’d grown older, but since he was by no means anything like a person devoid

of

sensibility and imagination, he often also reproached himself bitterly for

neglecting the duty of being at least a little happy. This was yet another

neglect of duty, a new one, which with perfect acuity demonstrated that the

dutiful never quite succeed in fulfilling all their duties, indeed, that such

individuals are the most likely of all human beings to disregard their foremost

duties and only later—perhaps when it’s already too late—call them once more

to

mind. On more than one occasion Dr. Klaus felt sad about himself when he thought

of the precious happiness that had faded from his view, the happiness of finding

himself united with a young sweet girl, who of course would have to have been

a

girl from an impeccable family. At around the same time as he was contemplating

his own person in a melancholy frame of mind, he wrote to his brother Simon,

whom he genuinely loved and whose conduct in this world troubled him, a letter

whose contents were approximately as follows:

Dear Brother,

It would appear you are refusing to tell me anything about yourself.

Perhaps things aren’t well with you and this is why you don’t write. You are

once more, as so often before, lacking a solid steady occupation—I’ve been sorry

to hear this, and to hear it from strangers. From you, it seems, I can no longer

expect any candid reports. Believe me, this pains me. So very many things now

cause me displeasure, and must you too—who always seemed to me to hold such

promise—contribute to the bleakness of my mood, which for many reasons is far

from rosy? I shall continue to hope, but if you are still even a little bit fond

of your brother, please don’t make me hope in vain for too long. Go and do

something that might justify a person’s belief in you in some way or other. You

have talent and, as I like to imagine, possess a clear head; you’re clever too,

and all your utterances reflect the good core I’ve always known your soul

possesses. But why, acquainted as you are with the way this world is put

together, do you now display so little perseverance? Why are you always leaping

from one thing to the next? Does your own conduct not frighten you? You must

possess quite a stockpile of inner strength to endure this constant change of

professions, which is such a disservice to yourself in this world. In your

shoes, I would have despaired long ago. I really cannot understand you at all

in

this, but for precisely this reason—that after experiencing all too often that

nothing can be achieved in this world without patience and goodwill—I’m not

abandoning my hope of one day seeing you energetically seize hold of a career.

And surely you wish to achieve something. In any case, such a lack of ambition

is hardly like you, in my experience. My advice to you is: Stick it out, knuckle

under, pursue some difficult task for three or four short years, obey your

superiors, show that you can perform, but also show that you have character,

and

then a career path will open before you—and it will lead you through all the

known world if you desire to travel. The world and its people will show

themselves to you quite differently once you yourself are truly something: when

you are in a position to mean something to the world. In this way, it seems to

me, you will perhaps find far more satisfaction in life than even the scholar

who (though he clearly recognizes the strings from which all lives and deeds

depend) remains chained to the narrow confines of his study but nonetheless,

as

I can report from experience, is often not so terribly comfortable. There’s

still time for you to become a quite splendidly serviceable businessman, and

you

have no idea to what an extent businessmen have the opportunity to design their

existences to be the most absolutely liveliest of lives. The way you are now,

you’re just creeping around the corners and through the cracks of life: This

should cease. Perhaps I ought to have intervened earlier, much earlier; maybe

I

ought to have helped you more with deeds than with mere words of warning, but

I

don’t know, given your proud mind, with its one determination to be helped only

by yourself in every way possible, perhaps I’d have done more to offend than

to

genuinely convince you. What are you now doing with your days? Do tell me about

them. Given all the worries I’ve endured on your behalf, I might now perhaps

deserve your being somewhat more loquacious and communicative. As for me, what

sort of a person am I? Someone to be wary of approaching unreservedly and with

trust? Do you consider me a person to be feared? What is it about me which makes

you wish to avoid me? Perhaps our circumstance? That I am the “big brother” and

possibly know a bit more than you? Well then, know that I would be glad to be

young again, and impractical, and naïve. And yet I am not quite so glad, dear

brother, as a person should be. I am unhappy. Perhaps it’s too late for me to

become happy. I’ve now reached an age when a man who still has no home of his

own cannot think of those happy individuals who enjoy the bliss of seeing a

young woman occupied with running their households without the most painful

longing. To love a girl, what a lovely thing this is, brother. And it’s beyond

my reach. —No, you really have no need to fear me, it is I who am seeking you

out once more, who am writing to you, hoping to receive a warm friendly

response. Perhaps you are now in fact richer than I—perhaps you have more hopes

and far more reason to have them, have plans and prospects I myself cannot even

dream of—the thing is: I don’t fully know you anymore. How could I after all

these years of separation? Let me make your acquaintance once more, force

yourself to write to me. Perhaps one day I shall enjoy the good fortune of

seeing all my brothers happy; you, in any case, I should like to see content.

What is Kaspar up to? Do you write to one another? What about his art? I’d love

to have news of him as well. Farewell, brother. Perhaps we shall speak together

again soon.