The Tanners (2 page)

Authors: Robert Walser

Whether or not that was actually the case, it is a fact that both died in

the same year, 1956––Walser, as is well known, on a walk he took on the 25th of

December, and my grandfather on the 14th of April, the night before Walser's last

birthday, when it snowed once more even though spring was already underway. Perhaps

that is the reason why now, when I think back to my grandfather's death, to which

I

have never been able to reconcile myself, in my mind's eye I always see him lying

on

the horn sledge on which Walser's body––after he had been found in the snow and

photographed––was taken back to the asylum. What is the significance of these

similarities, overlaps, and coincidences? Are they rebuses of memory, delusion of

the self and of the sense, or rather the schemes and symptoms of an order underlying

the chaos of human relationship, and applying equally to the living and the dead,

which lies beyond our comprehension? Carl Seelig relates that once, on a walk with

Robert Walser, he had mentioned Paul Klee––they were just on the outskirts of the

hamlet of Balgach––and scarcely had he uttered the name than he caught sight, as

they entered the village, of a sign in an empty shop window bearing the words

Paul Klee––Carver of Wooden Candlesticks

. Seelig does not attempt to

offer an explanation for the strange coincidence. He merely registers it, perhaps

because it is precisely the most extraordinary things which are the most easily

forgotten. And so I too will just set down without comment what happened to me

recently while reading

The Robber

, the only one of Walser's longer works

with which I was at the time still unfamiliar. Quite near the beginning of the book

the narrator states that the Robber crossed Lake Constance by moonlight. Exactly

thus––by moonlight––is how, in one of my own stories, Aunt Fini imagines the young

Ambros crossing the selfsame lake, although, as she makes a point of saying, this

can scarcely have been the case in reality. Barely two page further on, the same

story relates how, later, Ambros, while working as a room service waiter at the

Savoy in London, made the acquaintance of a lady from Shanghai, about whom, however,

Aunt Fini knows only that she had a taste for brown kid gloves and that, as Ambros

once noted, she marked the beginning of his

Trauerlaufbahn

(career in

mourning). It is a similarly mysterious woman clad all in brown, and referred to by

the narrator as the Henri Rousseau woman, whom the Robber meets, two pages on from

the moonlit scene on Lake Constance, in a pale November wood––and nor is that all:

a

little later in the text, I know not from what depths, there appears the word

Trauerlaufbahn

, a word which I believed, when I wrote it down at the

end of the Savoy episode, to be an invention entirely my own. I have always tried,

in my own works, to mark my respect for those writers with whom I felt an affinity,

to raise my hat to them, so to speak, but it is one thing to set a marker in memory

of a departed colleague, and quite another when one has the persistent feeling of

being beckoned to from the other side.

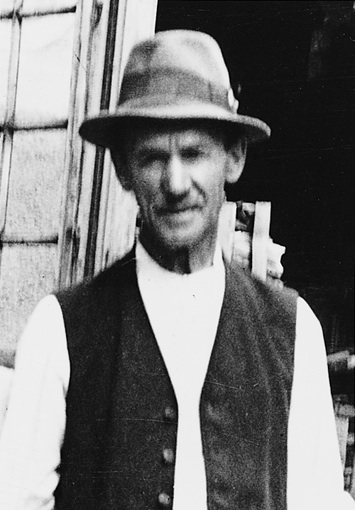

Who and what Robert Walser really was is a question to which, despite my

strangely close relationship with him, I am unable to give any reliable answer. The

seven photographic portraits of him, as I have said, show very different people; a

youth filled with a quiet sensuality; a young man hiding his anxieties as he

prepares to make his way in bourgeois society; the heroic-looking writer of brooding

aspect in Berlin; a 37-year-old with pale, watery-clear eyes; the Robber, smoking

and dangerous-looking; a broken man; and finally the asylum inmate, completely

destroyed and at the same time saved. What is striking about these portraits is not

only how much they differ, but also the palpable incongruity inherent in each––a

feature which, I conjecture, stems at least in part from the contradiction between

Walser's native Swiss reserve and utter lack of conceit, and the anarchic, bohemian

and dandyesque tendencies he displayed at the beginning of his career, and which he

later hid, as far as possible, behind a façade of solid respectability. He himself

relates how one Sunday he walked from Thun to Berne wearing a "louche pale yellow

summer suit and dancing pumps" and on his head a "deliberately dissolute, daring,

ridiculous hate." Sporting a cane, in Munich he promenades through the Englischer

Garten to visit Wedekind, who shows a lively interest in his loud check suit––quite

a compliment, considering the extravagant fashion in vogue among the Schwabinger

bohème

at the time. He describes the walking outfit he work on the long

trek to Würzburg as having a "certain southern Italian appearance. It was a sort of

species of suit in which I could have been seen to advantage in Naples. In

reasonable, moderate Germany however it seemed to arouse more suspicion than

confidence, more repulsion than attraction. How daring and fantastical I was at

twenty-three!" A fondness for conspicuous costume and the dangers of indigence often

go hand in hand. Hölderlin, too, is said to have had a definite penchant for fine

clothes and appearance, so that his dilapidated aspect at the beginning of his

breakdown was all the more alarming to his friends. Mächler recalls how Walser once

visited his brother at the island of Rügen wearing threadbare and darned trousers,

even though the latter had just made him a present of a brand-new suit, and in this

context cites a passage of

The Tanners

in which Simon is reproached by his

sister thus: "For example, Simon, look at your trousers: all ragged at the bottom!

To be sure, and I know this perfectly well myself: They're just trousers, but

trousers should be kept in just as good a condition as one's soul, for when a person

wears torn, ragged trousers it displays carelessness, and carelessness is an

attribute of the soul. Your soul must be ragged too." This reproach may well go back

to remarks Lisa was at times won't to make about her brother's appearance, but the

inspired turn of phrase at the end––the reference to the ragged soul––that, I think,

is an original aperçu on the part of the narrator, who is under no illusion as to

how things stand with his inner life. Walser must at the time have hoped, through

writing, to be able to escape the shadows which lay over his life from the

beginning, and whose lengthening he anticipates at an early age, transforming them

on the page from something very dense to something almost weightless. His ideal was

to overcome the force of gravity. This is why he had no time for the grandiose tones

in which the "dilettantes of the extreme left," as he calls them, were in those days

proclaiming the revolution in art. He is no Expressionist visionary prophesying the

end of the world, but rather, as he says in the introduction to Fritz Kocher's

Essays, a clairvoyant of the small. From his earliest attempts on, his natural

inclination is for the most radical minimization and brevity, in other words the

possibility of setting down a story in one fell swoop, without any deviation or

hesitation. Walser shares this ambition with the Jugendstil artists, and like them

he is also prone to the opposite tendency of losing himself in arabesques. The

playful––and sometimes obsessive––working in with a fine brush of the most abstruse

details is one of the most striking characteristics of Walser's idiom. The

word-eddies and turbulence created in the middle of a sentence by exaggerated and

participial constructions, or conglomerations of verbs such as "haben helfen dürfen

zu verhindern" ("have been able to help to prevent"); neologisms, such as for

example "das Manschettelige" ("cuffishness") or "das Angstmeierliche"

("chicken-heartedness"), which scuttle away under our gaze like millipedes; the

"night-bird shyness, a flying-over-the-seas-in-the-dark, a soft inner whimpering"

which, in a bold flight of metaphor, the narrator of

The Robber

claims

hovers above one of Dürer's female figures; deliberate curiosities such as the sofa

"squeaching" ("gyxelnd") under the charming weight of a seductive lady; the

regionalisms, redolent of things long fallen into disuse; the almost manic

loquaciousness––these are all elements in the painstaking process of elaboration

Walser indulges in, out of a fear of reaching the end too quickly if––as is his

inclination––he were to set down nothing but a beautifully curved line with no

distracting branches or blossoms. Indeed, the detour is, for Walser, a matter of

survival. "These detours I'm making serve the end of filling time, for I really must

pull off a book of considerable length, otherwise I'll be even more deeply despised

than I am now." On the other hand, however, precisely these linguistic

montages––emerging as they do from the detours and digressions of narrative and,

especially, of form––are exactly what is most at odds with the demands of high

culture. Their associations with nonsense poetry and the word-salad symptomatic of

schizophasia were never likely to increase the market value of their author. And yet

it is precisely his uniquely overwrought art of formulation which true readers would

not be without for the world, for example in this passage from the

Bleistiftsgebiet

(Pencil Regions) which, comic and heartbreaking in

equal measure, condense a whole romantic melodrama into the space of a few lines.

What Walser achieves her is the complete and utter subjugation of the writer to the

language, a pretense at awkwardness brought off with the utmost virtuosity, the

perfect realization of that irony only ever hinted at by the German Romantics yet

never achieved by any of them, with the possible exception of Hoffman, in their

writings. "In vain, the passage in question tells us, regarding the beautiful Herta

and her faithless Italian husband, "did she buy, in the finest first class

boutiques, for her most highly respected darling rake and pleasure-seeker, a new

walking cane, say, or the finest and warmest coat which she could find, procure or

purchase. His heart remained indifferent beneath the carefully chosen item of

clothing and the hand hard which used the can, and while this scoundrel––oh that we

might be permitted to call him thus––frivolously flitted or flirted around, there

trickled from those big tragic eyes, embellished by heartache with dark rims, heavy

tears like pearls, and here we must remark, too, that the rooms where such intimate

misfortune was played out were fairly brimming with gloomy, fantastically

be-palmleaved decoration gilded further by the height and scale of the whole.

"Little sentence, little sentence"––so Walser concludes this escapade which is all

but grammatically derailed by the end, "you seem to me fantastical as well, you do!"

And then, coming down to earth, he adds the sober phrase, "But let us continue."

But let us continue. As the fantastical elements in Walser's prose works

increase, so too their realistic content dwindles––or, rather, reality rushes past

unstoppably as in a dream, or in the cinema. Ali Baba, quite hollowed out by

unrequited love and pious devotion to duty in the diligent service of the most cruel

of all princesses, and in whom we easily recognize one of Walser's alter egos––Ali

Baba one evening sees a long sequence of cinematic images unfold before his eyes:

naturalistic landscapes like the many-peaked Engadin, the Lac de Bienne and the

Kurhaus at Magglingen. "One after another," the story continues, "there came into

view a Madonna holding a child on her arm, a snowfield high in the Alps, Sunday

pleasures by the lakeside, baskets of fruit and flower arrangements, all of a sudden

a painting representing the kiss Judas gave Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, with

his fat face, round as an apple, almost preventing him from carrying out his plan;

then a scene from a

Schüzenfest

, and, civility itself, a collection of

summer hats which seemed to smile contentedly, followed by expensive crystal,

porcelain, and items of jewelry. Ali Baba enjoyed watching the pictures, each

quickly dissolving and being replaced by the next." Things are always quickly

dissolving and being replaced by the next in Walser. His scenes only last for the

blink of an eyelid, and even the human figures in his work enjoy only the briefest

of lives. Hundreds of them inhabit the

Bleistiftsgebiet

alone––dancers and

singers, tragedians and comedians, bar-maids and private tutors, principals and

procurers, Nubians and Muscovites, hired hands and millionaires, Aunts Roka and Moka

and a whole host of other walk-on parts. As they make their entrance they have a

marvelous presence, but as soon as one tries to look at them more closely they have

already vanished. It always seems to me as if, like actors in the earliest films,

they are surrounded by a trembling, shimmering aura which makes their contours

unrecognizable. They flit through Walser's fragmentary stories and embryonic novels

as people in dreams flit through our heads at night, never stopping to register,

departing the moment they have arrived, never to be seen again. Benjamin is the only

one among the commentators who tries to pin down the anonymous, evanescent quality

of Walser's characters. They come, he says, "from insanity and nowhere else. They

are figures who have left madness behind them, and this is why they are marked by

such a consistently heartrending, inhuman superficiality. If we were to attempt to

sum up in a single phrase the delightful yet also uncanny element in them, we would

have to say: they have all been healed."

1

Nabokov surely had something similar in mind when he said of the fickle souls who

roam Nikolai Gogol's books that here we have to do with a tribe of harmless madmen,

who will not be prevented by anything in the world from ploughing their own

eccentric furrow. The comparison with Gogol is by no means farfetched, for if Walser

had any literary relative or predecessor, then it is Gogol. Both of them gradually

lost the ability to keep their eye on the center of the plot, losing themselves

instead in the almost compulsive contemplation of strangely unreal creations

appearing on the periphery of their vision, and about whose previous and future fate

we never learn even the slightest thing. There is a scene which Nabokov quotes in

his book on Gogol, where we are told that the hero of

Dead Souls

, our Mr.

Chichikov, is boring a certain young lady in a ballroom with all kinds of

pleasantries which he had already uttered on numerous occasions in various places,

for example "In the Government of Simbirsk, at the house of Sofron Ivanovich

Bezpechnoy, where the latter's daughter, Maria Gavrilovna, Alexandra Gavrilovna and

Adelheida Gavrilovna; at the house of Frol Vasilievich Pobedonosnoy, in the

Government of Penza; and at that of the latter's brother, where the following were

present: his wife's sister Katherina Mikhailovna and her cousins Rosa Feodorovna and

Emilia Feodorovna; in the Government of Viatka, at the house of Pyotr

Varsonophyevich, where his daughter-in-law's sister Pelagea Egorovna was present,

together with a niece, Sophia Rostislavna and two stepsisters: Sophia Alexandrovna

and Maclatura Alexandrovna"

2

––this scene, none of whose

characters makes an appearance anywhere else in Gogol's works, since their secret

(like that of human existence as a whole) resides in their utter superfluity––this

scene with its digressive nature could equally well have sprung from Robert Walser's

imagination. Walser himself once said that basically he was always writing the same

novel, from one prose work to the next––a novel which, he says, one could describe

as "a much-chopped up or dismembered Book of Myself." One should add that the main

character––the

Ich

––almost never makes an appearance in this

Ich–Buch

but is left blank, or rather remains out of sight among the

crowd of other passing figures. Homelessness is another thing Walser and Gogol have

in common––the awful provisionality of their respective existences, the prismatic

mood swings, the sense of panic, the wonderfully capricious humor steeped at the

same time in blackest heartache, the endless scraps of paper and, of course, the

invention of a whole populace of lost souls, a ceaseless masquerade for the purpose

of autobiographical mystification. Just as, at the end of the spectral story

The

Overcoat

, there is scarcely anything left of the scribe Akakiy Akakievich

because, as Nabokov points out, he no longer quite knows if he is in the middle of

the street or in the middle of a sentence, so too in the end it becomes almost

impossible to make out Gogol and Walser among the legions of their characters, not

to mention against the dark horizon of their looming illness. It is through writing

that they achieved this depersonalization, through writing that they cut themselves

off from the past. Their ideal state is that of pure amnesia. Benjamin noted that

the point of every one of Walser's sentences is to make the reader forget the

previous one, and indeed after

The Tanners

––which is still a family

memoir––the stream of memory slows to a trickle and peters out in a sea of oblivion.

For this reason it is particularly memorable, and touching, when once in a while,

in

some context or another, Walser raises his eyes from the page, looks back into the

past and imparts to his read––for example––that one evening years ago he was caught

in a snowstorm on the Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and how the vividness of the memory

has stayed with him ever since. Nor are Walser's emotions any less erratic than

these remembered images. For the most part they are carefully concealed, or, if they

do emerge, are soon turned into something slightly ridiculous or at least made light

of. In the prose sketch devoted to Brentano, Walser asks: "Can a person whose

feelings are so many and so lovely be at the same time so unfeeling?" The answer

might have been that in life, as in fairy tales, there are those who, out of fear

and poverty, cannot afford emotions and who therefore, like Walser in one of his

most poignant prose pieces, have to try out their seemingly atrophied ability to

love on inanimate substances and objects unheeded by anyone else––such as ash, a

needle, a pencil, or a matchstick. Yet the way in which Walser then breathes life

into them, in an act of complete assimilation and empathy, reveals how in the end

emotions are perhaps most deeply felt when applied to the most insignificant things.

"Indeed," Walser writes about ash, "if one goes into this apparently uninteresting

subject in any depth there is quite a lot to be said about it which is not at all

uninteresting; if, for example, one blows on ash it displays not the least reluctant

to fly off instantly in all directions. Ash is submissiveness, worthlessness,

irrelevance itself, and best of all, it is itself pervaded by the belief that it is

fit for nothing. Is it possible to be more helpless, more impotent, and more

wretched than ash? Not very easily. Could anything be more compliant and more

tolerant? Hardly. Ash has no notion of character and is further from any kind of

wood than dejection is from exhilaration. Where there is ash there is actually

nothing at all. Tread on ash, and you will barely notice that your foot has stepped

on something." The intense pathos of this passage––there is nothing which comes near

it in the whole of twentieth-century German literature, not even in Kafka––lies in

the fact that here, in this apparently casual treatise on ash, needle, pencil and

matchstick, the author is in truth writing about his own martyrdom, for these four

objects are not randomly strung together but are the writer's own instruments of

torture, or at any rate that which he needs in order to stage his own personal

auto-da-fé––and what remains once the fire has died down.