The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam (49 page)

Read The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam Online

Authors: Jerry Brotton

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Turkey & Ottoman Empire, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Renaissance

A needlework hanging showing a personification of Faith—looking remarkably like Queen Elizabeth—and Muhammad, commissioned by Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury, at the height of the Anglo-Ottoman accord.

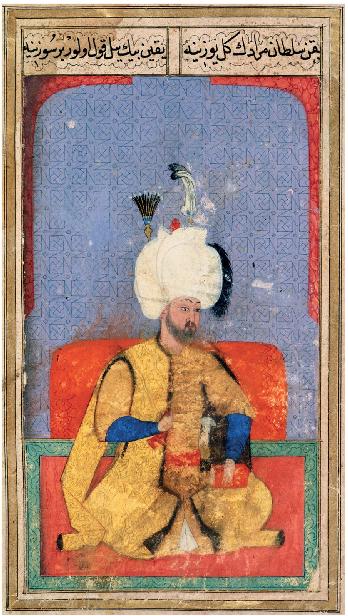

A portrait of Sultan Murad III from an Ottoman album of 1588–1589. Murad and Queen Elizabeth corresponded about politics and commerce for more than two decades and established an unprecedented alliance. When Ottoman forces were confronting Spain and challenging the Holy Roman Empire, Elizabeth’s merchants were supplying them with guns.

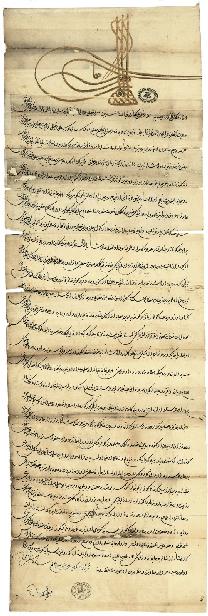

A copy of a letter from Sultan Murad III to Queen Elizabeth dated June 20, 1590, in praise of the queen, with the Ottoman calligraphic monogram at the top.

Nicholas Hilliard’s Heneage Jewel, c. 1595, made of gold, diamonds, crystal, and rubies. Elizabeth sent jeweled portraits like this to the Ottoman court in the 1590s.

Sir Anthony Sherley and his rival ambassador, the Persian cavalryman Husain Ali Beg Bayat, engraved by Aegidius Sadeler during their joint embassy to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague in 1600 to propose a Euro-Persian alliance. The two men quarreled violently before Ali Beg finally abandoned Sir Anthony and returned to Persia.

Sir Robert Sherley and his wife, Teresa, painted in an opulent oriental style by Sir Anthony Van Dyck during Sherley’s embassy to Rome in 1622. The daughter of a Circassian chieftain, Teresa was baptized into the Catholic faith.

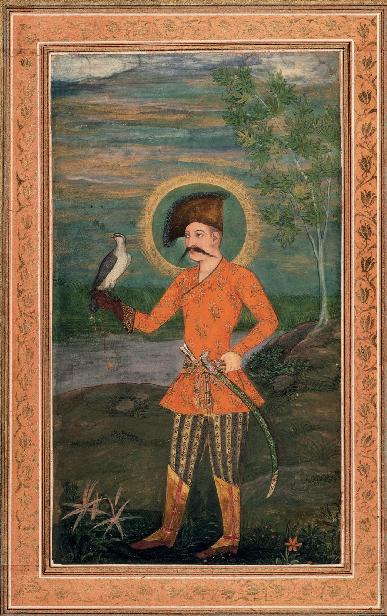

The Persian shah Abbas I, Safavid ruler of Iran, from a seventeenth-century Mughal painting. Falconry was one of his passions, shared by his friend Sir Anthony Sherley.

Constantinople, the Ottoman capital, in the early seventeenth century. The skyline is dominated by minarets, characteristic of the Ottoman architecture that redefined the Byzantine city after it fell to Mehmed II in 1453.

A conference at Somerset House in 1604 brought about reconciliation with Spain and marked the end of Elizabethan engagement with Islam. The English delegates are on the right, the Spanish and Flemish on the left; on the table between them is an Ottoman rug.

Acknowledgments

Writing acknowledgments brings with it the realization that the origins of a book often go back much further than its author has appreciated. In my case they reach all the way to my inspirational English teacher in secondary school, Maggie Sheen, who first interested me in Shakespeare. She started me on a path that eventually led to this book, and to another important figure in my life, my great mentor, collaborator and friend Lisa Jardine. In the 1990s Lisa and I worked together on exchanges between western and eastern cultures in the Renaissance. Lisa’s untimely death in the autumn of 2015 robbed Britain of one of its great public intellectuals, and it left me bereft of a dear friend and confidante who made me believe anything was possible. I wish she were still with us for many reasons, not least to see the publication of a book that, like its subject, is haunted by her absent presence.

Family and friends provided practical support, shrewd guidance and less tangible but equally crucial care and encouragement as I tussled with this book. For that I would like to thank Peter Barber, Jonathan Burton, Miles and Ranj Carter, Rebecca Chamberlain, Nick Crane, Kath Diamond, Simon Curtis, Dave and Sarah Griffiths, Lucy Hannington and Bence Hegedus, Helen Leblique, Ita MacCarthy, Nabil Matar, Nick Millea, Patricia Parker, Richard Scholar, Vik Sivalingam, Guy Richards Smit, Tim Supple, Ben and Katherine Turney, Dave and Emily Vest and Dan Vitkus. Emma and James Lambe provided their characteristically unwavering calm and unhesitating domestic help. Alexander Samson kindly shared unpublished research with me, Mia Hewitt and Alice Agossini helped translate documents from the Spanish, Ton Hoenselaars read related articles and encouraged me to continue writing when I thought the project had defeated me, as did my dear old friend Maurizio Calbi. I am grateful to Patrick Spottiswoode, director of education at the Globe Theatre, for inviting me to hold the International Shakespeare Globe Fellowship in 2004 on the topic “Shakespeare and Islam,” which allowed me to develop some of this book’s ideas; to William Dalrymple, for allowing me a memorable opportunity to present the work in Jaipur; and to Peter Florence, who generously allows me to say and do marvelous things at his remarkable festivals in Hay and beyond. My agent, Peter Straus, has supported me tirelessly for a decade now, and I’m glad to have him by my side. At Viking, I wish to thank Joy De Menil for her tireless and exacting editorial work, as well as the rest of her team, especially Benjamin Sandman, Haley Swanson and Bruce Giffords. Once again Cecilia Mackay proved herself to be the best picture researcher in the business.

Every book I have ever written has celebrated the unique environment provided by Queen Mary University of London, where I have studied and worked for over twenty years. A dedicated team of people within the School of English and Drama make my working environment a real pleasure, and for that I want to thank Faisal Abul, Jonathan Boffey, Richard Coulton, Rob Ellis, Jenny Gault, Patricia Hamilton, Suzi Lewis, Huw Marsh, Matthew Mauger, Kate Russell and Bev Stewart. I am also proud to be an associate of the People’s Palace Projects at Queen Mary, led by the inspirational Paul Heritage, and thank him and his team, especially Rosie Hunter and Thiago Jesus, for allowing me to work with them in Brazil on Shakespeare and many other exciting initiatives. Among my departmental colleagues I am lucky enough to have the support and friendship of Ruth Ahnert, John Barrell (who goes back even further), Michèle Barrett, Julia Boffey, Mark Currie, Markman Ellis, Katie Fleming, Paul Hamilton, Alfred Hiatt, Pete Mitchell, Claire Preston, Kirsty Rolfe, Morag Shiach, Bill Schwarz and Andrew van der Vlies. Acting as associate director on my old friend David Schalkwyk’s Global Shakespeare project has also given me fantastic opportunities to explore Shakespeare beyond this sceptered isle. It would embarrass David Colclough were I to tell him how much I cherish our enduring friendship, so I will stop here. I seem to have a weakness for Miltonists, because Joad Raymond has become a great friend since his arrival at Queen Mary, and I hope our alliance will generate more than one Penguin.