The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (24 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

ho will I marry? How long will I live? What’s the winning number? Will this product sell? Will this plane crash? Will we win the war?

ho will I marry? How long will I live? What’s the winning number? Will this product sell? Will this plane crash? Will we win the war?

Everyone from lovestruck teenagers to world leaders wants to know what lies ahead. That’s why divination—the art of foretelling the future—has existed in some form in every culture in recorded history. Today, one can find practitioners of the most popular forms of divination—

astrology

, tarot card reading,

crystal-ball

gazing, palm reading, numerology, and

tea-leaf reading

—in most any city. And these examples are only a tiny sample of hundreds of divinatory systems that have been developed over the centuries.

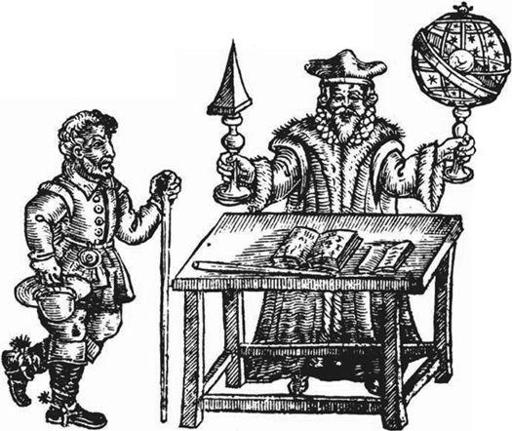

The hat, robes, wand, and books of the fortune-teller made him instantly recognizable. This seventeenth-century diviner holds an astrolabe to symbolize his knowledge of astrology

. (

photo credit 19.1

)

Many methods of divination began in ancient Mesopotamia more than 4,000 years ago. There, the divinatory arts were practiced by the priests, who studied the movements of the stars and planets and examined the entrails of sacrificed animals for clues to the welfare of the king and community. Some diviners sought clues to future events by going into a trance and seeking guidance from the spirit world. Others looked for omens in nature. An eclipse, a hailstorm, the birth of twins, or the way smoke drifted through the air—almost anything might be interpreted as a sign of things to come.

In ancient Greece and Rome, there were two levels of divination: Professional, highly trained diviners worked for the government, while ordinary fortune-tellers worked for anyone who could afford them. Of the official diviners, the most esteemed in Greece was the Oracle of Delphi (see

Prophecy

), to whom petitioners would bring their questions and receive an answer directly from the god Apollo, as channeled through a priestess. Royal emissaries from neighboring lands consulted the Oracle on such important matters as where to construct a new temple or whether to go to war. In Rome, the state-appointed diviners were known as “augurs,” from the Latin

avis

, meaning “bird,” and

garrire

, meaning “to chatter.” Indeed, their highly regarded counsel to the empire was based on bird watching. Of all earth’s creatures, birds were the closest to the heavens, so it’s understandable that they were regarded as good indicators of what might or might not please the gods. Interpretations were based on many kinds of observations, including the number and species of birds and their flight patterns, calls and songs, direction, and speed. Julius Caesar, Cicero, Mark Antony, and other eminent Romans all served as augurs.

Less noteworthy diviners were available to most everyone (even slaves were sometimes permitted a consultation), and fortune-telling was a booming business throughout the ancient world.

Dream

interpretation and astrology were the most venerable systems, but also popular were

arithmancy

, scrying (a relative of crystal-ball gazing), and

palmistry

, as well as systems involving birds, dice, books, arrows, axes, and other surprising items. Popular fortune-tellers, many of whom also sold

talismans

and

amulets

, were not afforded the respect given official diviners. They were more likely to be deliberate frauds, and humorists enjoyed poking fun at those who flocked to them for advice on every trivial matter.

People from all walks of life consulted professional fortune-tellers. Here a young nobleman learns what the cards reveal about his future

. (

photo credit 19.2

)

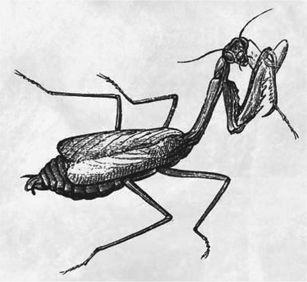

What does the fearsome green predator of the insect kingdom known as the praying mantis have in common with systems of fortune-telling? Not much, really, except for an interesting connection in language: the Greek word

mantikos

, which means “prophet.” Because of the prophetic nature of fortune-telling, diviners are sometimes said to practice “the mantic arts,” and dictionary makers use the word ending “-mancy” to indicate any form of divination. Palm reading is chiromancy (

cheiro

is Greek for “hand”), dream interpretation is oneiromancy (in Greek

oneiros

means “dream”), and so forth. The voracious garden mantis derives its name from the typical upraised position of its forelegs, which suggests a prophet with his hands held together in prayer. Usually, however, the praying mantis is more concerned with “prey” than with either fortune-telling or heavenly supplication.

(

photo credit 19.3

)

Many ancient divinatory systems survived into the Middle Ages, despite opposition in Europe from the Church. Professional seers continued to work in major cities, traveling fortune-tellers moved from town to town, and village

wizards

and wise women served as diviners for their communities. Village wizards, it should be noted, were expected to look toward the past as well as the future. They were frequently asked to find lost objects, identify thieves, discover the whereabouts of missing persons, and locate buried treasure (centuries ago, when banks were few and far between, many people buried their valuables in a hole in the ground, a practice which led others to try to locate them and dig them up). Ordinary folks were also able to practice some do-it-yourself divination, which they learned from the cheap illustrated booklets on palmistry, astrology, and other subjects that could be purchased as early as the sixteenth century. For the most part, however, divination remained in the hands of professionals who claimed to have information, training, and “a gift” not available to others.

Two additional systems of divination were added to the fortuneteller’s arsenal in later centuries. Cartomancy—divination using playing cards—was developed around the mid-seventeenth century, about 150 years after playing cards first appeared in Europe, and soon became the trademark system of wandering gypsy fortune-tellers. Tasseomancy—divination by tea leaves—although practiced in China from about the sixth century, did not appear in Europe until the mid-eighteenth century. These new systems quickly became quite popular, perhaps because card playing and tea drinking were already part of everyday life. Although many ancient systems of divination have now been abandoned, all of those taught at Hogwarts remain in use to this day.