The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (20 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

eautiful and deadly, charming and cruel, Circe is one of the great

eautiful and deadly, charming and cruel, Circe is one of the great

witches

of Greek mythology. Aided by her wand,

potions

, herbs, and incantations, she transformed men into animals, caused forests to move, and turned day into night. The ancient writers Homer, Hesiod, Ovid, and Plutarch all chronicled her exploits, ensuring her place in legend—and as a Chocolate Frogs trading card.

Circe’s wand and potions were powerless against Odysseus. This illustration comes from an 1887 edition of

The Odyssey. (

photo credit 14.1

)

The daughter of the sun god Helios and the ocean nymph Perse, Circe lived on the island of Aeaea off the coast of Italy, where she spent her days weaving dazzling fabrics on her loom and singing in a most enchanting voice. She was occasionally visited by travelers who happened upon her island, or by those who knew of her magical powers and came to her for aid. But Aeaea was far more perilous than your typical island resort. The sea god Glaucus discovered this when he came to Circe for a love potion to help him win his heart’s desire, a nymph named Scylla. Circe fell in love with Glaucus and asked him to stay with her. When he refused, she threw poisonous herbs into the water where her rival was bathing, turning Scylla into a hideous monster with dogs’ heads and serpents protruding from her body. Another man foolish enough to reject Circe spent the rest of his days as a woodpecker.

The best-known visitors to Circe’s island were the Greek hero Odysseus and his crew of sailors, who landed on Aeaea on their return from the Trojan War. Seeing a wisp of smoke in the distance, Odysseus sent half of his men to investigate. They soon came upon the home of the enchantress, a marble palace in the middle of a forest clearing surrounded by tame bears, lions, and wolves that had been human until they met Circe. Always the welcoming hostess, Circe appeared at the door and invited the men to lunch. But the barley and cheese she served contained a powerful potion that deprived the men of both their memories and their desire to return home. As they sat in a contented stupor, Circe tapped each man with her

magic wand

, turned them into pigs and led them off, weeping, to the pigsty.

Circe planned the same fate for Odysseus, but on his way to find his men he was met by the god Hermes who gave him an herb called

moly

to neutralize the effect of her

spells

and potions. Powerless to work her magic against him, Circe instead befriended Odysseus and restored his sailors to human form. From then on she acted as his advisor, forecasting the dangers that lay ahead and explaining how to communicate with the

ghosts

he would meet in his journey to the underworld.

Myths about Circe, along with stories about the sorceress Medea (Circe’s niece) and the Greek goddess and witch Hecate, formed the basis for many popular beliefs about witches and witchcraft. During the Middle Ages, it was common for those who heard these myths to believe that Circe had been a real person and that her magical feats were within the realm of possibility.

et me look into my crystal ball…

et me look into my crystal ball…

.

Today these words are often heard as a sarcastic response to questions about the unknowable future. For those who practice the many arts of

divination

, however, crystal-ball gazing is serious business. At Hogwarts, Professor Trelawney instructs her third-years in the proper method of peering into the misty orb—assuring them that patience and relaxation will reward them with a view of things to come. Harry, Ron, and Hermione are skeptical at best, but those who believe in the revealing powers of the crystal ball are certainly not alone.

Although actual crystal balls were not used until the Middle Ages,

crystalomancy

—the art of gazing into natural or polished crystal in an attempt to see the future—is part of a much older tradition. It’s a form of

scrying

—a method of divination that involves staring at a clear or reflective surface until images begin to form, either within the object itself or else within the mind of the practitioner. All cultures seem to have practiced a form of scrying. In ancient Mesopotamia, diviners poured oil into bowls of water and interpreted the shapes that appeared on the surface. The biblical prophet Joseph carried a silver goblet, which he used for both drinking and scrying. The ancient Egyptians, Arabs, and Persians gazed into bowls of ink, while the Greeks stared at shiny mirrors and burnished brass in the hope of receiving enlightening visions. The Romans were the first true cystalomancers, preferring to peer at polished (though not neessarily round) crystals of quartz or beryl.

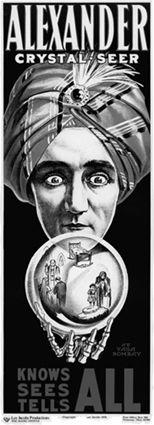

In the 1920s and 1930s, the vaudeville entertainer and mind reader Claude Alexander Conlin used a crystal ball to symbolize his ability to “know all, see all, and tell all.”

(

photo credit 15.1

)

Even back then, a skeptic like Hermione would have made a poor crystal gazer, since sincerity, a positive mental attitude, and faith in the process were said to be the keys to success. The ideal crystalomancer was supposed to be spiritually and physically pure, preparing for each reading with a few days of prayer and fasting. A special room with a solemn and ceremonial atmosphere would generally be used for the reading. Such preparation and attention to detail was intended to help the seer to reach a trancelike state while gazing at the crystal, making it more likely that images would appear in his or her mind. The ancients recognized that whatever crystalomancers saw came from their own minds and did not really form within the crystal itself. Nonetheless, these visions were treated as true

prophecies

and not mere daydreams.

In some traditions, children were thought to be the best scryers, since they were spiritually pure and likely to be more open to the imagination than adults. This theory was generally accepted in Renaissance Europe, where a child might be employed to foretell the future through a crystal-gazing ritual similar to that of the ancients, involving prayers, incense, and

magic words

. During this period, both children and adults also began peering into crystal balls for more practical purposes, such as discovering the identity of criminals or locating lost or stolen property. An account from 1671, for example, tells of a merchant who, upon finding himself constantly robbed of his goods, elected to wander the nearby streets at midnight with a young boy and girl, instructing them to gaze into a crystal until they saw the likeness of the thief. Whether he caught the right man, we’ll never know.

Undoubtedly the best-known crystal ball of the Renaissance belonged to John Dee, a highly respected English mathematician and astronomer who was hired to calculate the astrologically correct time for Queen Elizabeth I’s coronation in 1558. Dee was passionately interested in scrying as a way of contacting the world of angels and spirits, who he believed possessed knowledge unavailable elsewhere. He owned a crystal ball, which he described as “most bright, most clear and glorious, of the bigness of an egg.” Unfortunately, however, no matter how many hours Dee spent gazing into his ball, he could see nothing. Rather than give up, he hired Edward Kelly, a professional scryer who many scholars believe was a swindler. For years, the two men worked together, Dee asking questions while Kelly peered into the crystal ball and reported the answers. Together, Dee and Kelly produced volumes of spirit messages, including one predicting the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, which took place in February 1586. Dee’s crystal ball now resides in the British Museum in London, England.