The Sahara (33 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

The Sahara has appealed to filmmakers since the earliest days of cinema. Its appeal lies in its foreignness, limitless space, unending horizons and seas of dunes - all of which are supported by a degree of ignorance. The combination of these factors has led to many spectacular films in which the Sahara has played a leading role, even if never credited as such. Indeed , there are two types of film where the Sahara plays a starring role: first are those about lands far-removed from North Africa but set in the Sahara; and the second are films about the Sahara shot in far-removed lands. One of the most famous examples of the former is

Star Wars

(1977), where the dramatic troglodyte dwellings of Matmata in the Tunisian Sahara stand in for Luke Skywalker’s childhood home on the planet Tatooine, “a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.” This is not to be confused with the genuine Tunisian town of Tatouine, even though the director George Lucas did use the name for his imaginary planet. The place’s isolation is one important reason young Skywalker is keen to leave home and seek adventure.

In contrast, many great films with supposedly Saharan settings never see a member of the cast or crew going further than the American West or West London. Usually the high cost involved in shooting in foreign countries, the often stultifying bureaucracy of many Saharan nations and the frequent lack of suitable infrastructure make many directors reluctant to work on location.

The first major picture set in the Sahara was a silent film named

Sahara

and directed by C. Gardner Sullivan. One of the most prolific and accomplished early filmmakers, Sullivan was also responsible for the classic 1930 version of

All Quiet on the Western Front

.

Sahara

is a tragedy about love and betrayal in which a Parisian beauty marries an American engineer who goes to work in the desert with his wife and child. Unhappy with her life in the desert, his wife abandons the family and runs away to Cairo to live with a wealthy playboy. Years later, and still dissatisfied, the wife comes across her now blind, drug-addicted husband begging in the streets of Cairo with their child. The family are reunited and return to the desert and, surprisingly under the circumstances, live happily ever after. On its release in 1919, the New York Times described

Sahara

as “Desert sand and wind storms, picturesque Arabs, dashing horses, camels, beggars, turbans, flowing robes, bloomers and streets with the atmosphere of the Arabian Nights” - without mentioning the fact that it was filmed entirely in America.

Likewise, when directing

The Desert Song

(1929) Roy Del Ruth decided a journey to North Africa was unnecessary to capture the desert on film. As the promotional material says, “From out of the desert wastes of Morocco appeared a sinister figure. Men whispered his name-’Red Shadow!’” (And whispered it with an exclamation mark, no less!) The title song talks of “a desert breeze whispering a lullaby,” as it happens a Californian rather than a Saharan breeze, the film’s exteriors being shot on the Buttercup Dunes, a location which sounds as contrived as the film looks. Based on an earlier Broadway operetta, the film was promoted as containing “Romance, Adventure, Spectacle, Comedy, [which] Have been woven into one magnificent production - that will cause you to gasp - and agree that you’ve never seen anything like it.” Starring John Boles as the Red Shadow, and Carlotta King as the love interest, Boles plays a handsome bandit leader whose domain is beyond the control of the authorities in French-occupied Morocco. The Red Shadow is, we are told, “Beloved by the Riffs whom he commanded - feared by the French - a mystery as deep as the desert silence.”

Although it was the first colour film released by Warner Brothers, only a black and white print survives. Dated, it nonetheless remains important as Warner Brothers’ first all-talking, all-singing operetta that was, according to their publicity, “the greatest achievement of the modern motion picture”. However grand this claim, the subject matter demonstrates the early allure of the Sahara for filmmakers.

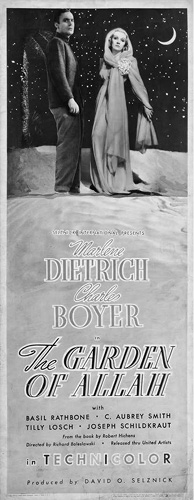

Romance in the Sahara was also central to the plot of

The Garden of Allah.

So popular was the story that three film versions were made between 1916 and 1936. Based on a 1904 novel by Robert Smythe Hichens, the first, silent adaptation of this tale of star-crossed love was filmed in America’s Mojave Desert. The second, also silent, version, filmed in 1927, starred Alice Terry and Ivan Petrovich, and was at least partly shot in Algeria, in Touggourt and Biskra. Clearly understanding what the audience expects from a Saharan film, the trailer promises “A thousand thrilling moments, fiery steeds, burning sands, flaming love, and a desert sandstorm that forms one of the most spectacular climaxes.”

The best-loved version of the film stars Marlene Dietrich as Domini Enfilden and Charles Boyer as Boris Androvsky, the renegade Trappist monk turned lover. This version, like

The Desert Song

, was partly filmed in Buttercup Valley, California. Mirroring the pitfalls inherent in the love affair of the romantic leads, the film portrays the desert as a dangerous environment where divine protection is required from the perils of nature, both environmental and of human passions. As Count Ferdinand Anteoni, played by Basil Rathbone in a pre-Sherlock Holmes guise, muses philosophically, ‘‘A man who refuses to acknowledge his god is unwise to set foot in the desert.”

An unconventional love affair is the subject of

Passion in the Desert

, a 1997 film based on a story by Honore de Balzac set in the Egyptian Sahara in the wake of the Napoleonic invasion. In the heat of a battle against a force of Mamelukes, Augustin Robert, a French officer played by Ben Daniels, becomes detached from his company: “The silence was awful in its wild and terrible majesty. Infinity, immensity, closed in upon the soul from every side. Not a cloud in the sky, not a breath in the air, not a flaw on the bosom of the sand, ever moving in diminutive waves; the horizon ended as at sea on a clear day, with one line of light, definite as the cut of a sword.” Balzac likewise had never visited the Sahara but his description is real enough:

... the dark sand of the desert spread farther than sight could reach in every direction, and glittered like steel struck with a bright light. It might have been a sea of looking glass, or lakes melted together in a mirror. A fiery vapour carried up in streaks made a perpetual whirlwind over the quivering land. The sky was lit with an Oriental splendour of insupportable purity, leaving naught for the imagination to desire. Heaven and earth were on fire.

Although less contemplative than

Passion in the Desert

,

The Four Feathers

also takes place in the wake of the occupation of the eastern Sahara. Based on the 1902 story by A. E. W Mason, late nineteenth-century Sudan is the main location, both in the novel and the seven film versions, from 1915 to the most recent, in 2002. The adaptation that perhaps best captures the feel of the late Victorian period, when the sun never set on the British Empire, is that directed by Hungarian-born Zoltan Korda, known for his love of African settings. Korda’s 1939 film, filmed partly on location in Sudan, is outstandingly dramatic and made firmly in the empire stamp.

On the eve of his regiment’s embarkation for the Sudan to battle the Mad Mahdi for control of the country, Harry Faversham, a young officer, resigns his commission. Stung by accusations of cowardice by his three closest friends and his fiancée, Faversham follows his erstwhile regiment to the Sudan determined to prove himself, and force his friends to take back the white feathers they gave him as a mark of cowardice. The parched Sudanese desert is captured in Technicolor and the film was considered one of the most advanced cinematic creations of its time. Two of its cast would later be knighted, Sir Ralph Richardson and Sir John Clements, who played Faversham.

On the other side of the Sahara, and a couple of decades after the events portrayed in

The Four Feathers, Fort Saganne

also has European occupiers and locals clashing in the desert. A 1984 French film set in French Algeria, it features Gerard Depardieu as the hero, Charles Saganne, who is battling not just the Algerians but his own lowly background, and the political games of those responsible for promoting and condemning French colonialism.

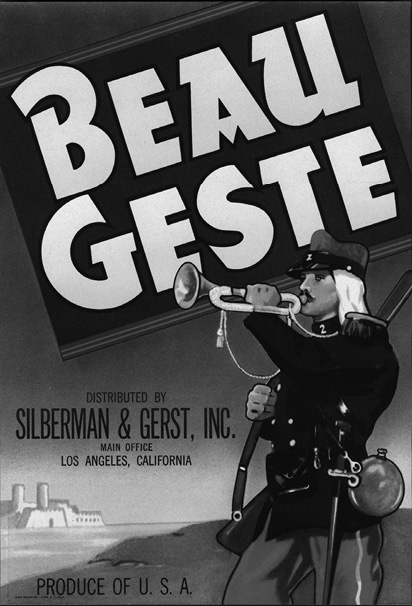

Beau Geste

Considering their lengthier and broader colonial experience there, it is perhaps appropriate that the French should take the laurels for the most famous Saharan story and its numerous film versions. The very title

Beau Geste

is enough to conjure up images of weary legionnaires in kepis, pitched battles against defiant Tuareg and a seemingly deserted Saharan fort. This classic high adventure desert movie, based on the 1924 book by P C. Wren, satisfied all the stereotypes of its day, including the heroic, upright British, a sadistic French sergeant-major and savage tribesmen.

Michael “Beau” Geste leaves home and joins the French Foreign Legion after the apparent theft of Blue Water, a precious stone belonging to his aunt who has raised Beau and his orphan brothers. By taking the blame for the alleged theft, Beau is satisfied that although these measures are drastic, he has done the right thing and saved something of the family’s honour. When they learn what he has done, Beau’s brothers, Digby and John, likewise run away from home and join the Legion, being as keen as Beau to make a conspicuous display of their chivalry.

The classic 1939 film version, starring Gary Cooper, Ray Milland and Robert Preston as the Geste brothers, was filmed in the deserts of Arizona. The importance of the desert is established before the first scene as the film’s title is revealed written in sand, only to be concealed by more sand carried on a desert wind. The story’s premise is summed up by an on-screen Arabian proverb that reads “The love of a man for a woman waxes and wanes like the moon... but the love of brother for brother is steadfast as the stars, and endures like the word of the prophet.”

A slow opening shot of an empty desert establishes the Sahara’s onscreen presence. Then, having crossed a sea of dunes, a relief column of the French Foreign Legion arrives at the embattled Fort Zinderneuf, only to find it silent but with its defenders still upright at their posts. With no signs of the enemy, we discover that the fort is mysteriously manned by the dead. As the story says, “Everybody does his duty at Zinderneuf, dead or alive!”

The book was an instant success upon publication, as was the first film version, which came out just two years later with the tagline, “Hard lives, quick deaths, undying love!” A silent film, it featured some of the biggest stars of the day, including Ronald Coleman as Beau.

The 1966 film version is the least true to the story, losing not only one of the Geste brothers but dispensing with the missing gem and family dishonour to have Beau appear instead as an American businessman determined to take the blame for embezzlement by a dishonest partner. Starring Guy Stockwell as Beau, Leslie Nielsen in a rare non-comedic role as Lieutenant De Ruse and Telly Savalas as the tyrannical Sergeant-Major Dagineau, the film is less gripping than either of the earlier versions, perhaps because of the unnecessary meddling with the plot. One of the few links to earlier versions of the film is that it too was filmed in Arizona, rather than the Sahara.