The Sahara (37 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

The idea of tourism proper only came about with the rise in leisure time enjoyed by an ever-growing number of Europeans, one result of the Industrial Revolution. Not coincidentally, the opportunity and ability to travel for pleasure was at first monopolized by wealthier citizens from those European nations responsible for the large-scale invasion of the region. By the late 1880s, when the Berlin Conference had established the rules by which European nations would play out the Scramble for Africa, France had claimed Algeria and Tunisia, and was making significant inroads into Chad, Mali and Mauritania. Britain, meanwhile, had occupied both Egypt and the Sudan, and Thomas Cook and Sons were selling Nile tours.

These first modern tourists, who were treated to excursions into the Sahara, paid a single price to cover the cost of the journey, accommodation and food. Thus the package holiday was born. Founded in 1841, Thomas Cook and Sons became massively successful, and not entirely through its package holidays. Business also boomed because the company won a contract to run a postal service between Britain and Egypt, the opportunity arising from Egypt’s unexpected declaration of bankruptcy and subsequent occupation by Britain. Visitors flooded the land in ever-greater numbers for the rest of that and the next century, sailing the Nile and stopping at the Pyramids in droves.

Instead of enjoying the desert, Anthony Trollope was wholly focused on government business - he was there to set up the Egyptian postal system - and meeting his daily word count. As he notes matter-of-factly in

An Autobiography

, “While I was in Egypt I finished Doctor Thorne and on the following day began

The Bertrams

.” Mark Twain was likewise there to write, casting his sardonic eye over his surroundings and the proceedings of the natives before writing in

The Innocents Abroad

: “[I] landed where the sands of the Great Sahara left their embankment... A laborious walk in the flaming sun brought us to the foot of the great Pyramid of Cheops. It was a fairy vision no longer. It was a corrugated, unsightly mountain of stone.”

More sympathetic, if no less disgruntled, William Golding wrote in

An Egyptian journal

about his holiday there after winning the 1983 Nobel Prize for Literature: “There was nothing about the scene to distinguish it from any river scene in any city. The pyramids, of course, were hidden by buildings.” To go beyond the pyramids and into the Sahara proper required, as it still does, a degree of planning that excluded all but those who were set on seeing more of the desert.

Early Observers

Before the First World War those parts of North Africa administered by Britain and France were seen as safe. In a sense, countries like Egypt and Algeria had ceased to be foreign, becoming instead part of European North Africa. As a result, increasing numbers of tourists, many of them writers, were travelling there.

Andre Gide (1869-1951) first travelled to these countries in 1893. In

Amyntas: North African Journals

, Gide writes:

I love the desert more than anything else. The first year I was a little afraid of it because of the wind, because of the sand... But last year I began taking immense walks, with no other purpose than to lose sight of the oasis. I would walk-!walked until I felt myself immensely alone in that vast expanse. Then I began to look. The sands had velvety touches of shadow under each hillock; there were wonderful rustlings in every breath of wind; because of the great silence, the least sound could be heard.

These notebooks, published in 1906, cover the five-year period Gide spent travelling in the region, and are rightly considered an important work in his development as a writer. Indeed, Gide once declared, “Few realize I have never written anything more perfect than

Amyntas

.”

Gide travelled widely in Algeria and Tunisia, and enjoyed the relaxation afforded by escaping the moral and sexual strictures of contemporary France. In the course of his travels he met Oscar Wilde in Blida, northern Algeria, in January 1895, just three months before Wilde’s libel trial against the Marquess of Queensberry. Although the two had met once before in Paris, both men were more at ease in North Africa because they were far As Gide records in his diaries, it was during his initial trip to French North Africa that he enjoyed his first homosexual and heterosexual encounters.

Of all Gide’s writings,

L’Immoraliste

draws most inspiration from the Sahara. A contemporary parable set in the desert, Gide described the book as “a fruit filled with bitter ashes. It is like those colocynths of the desert which grow in barren, burning places; you come to them parched with thirst and are left with a burning all the more fierce. Yet on the golden sands they are not without beauty.” The book, which was considered scandalous when it was published in 1902, deals with the rejection of societal norms by a newly married, upper-middle-class French couple travelling in North Africa, with results that are not positive for either party. As they move further from the French environment they are used to, the couple are able, or perhaps forced, to shed more and more layers of their Europeanism. The further into the Sahara he travels, the more the agnostic protagonist, Michel, finds himself enamoured with the beautiful young boys of the oases, feelings he keeps from his religious wife.

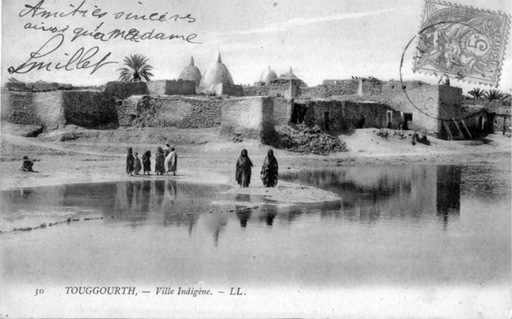

Having returned to France for a period, Michel and his wife then travel again to North Africa where Michel is disappointed by his former infatuations, who have either married or lost the beauty of youth. Although his wife is ill, his disillusionment forces them to travel further south where, in the sad oasis of Touggourt, his wife dies and Michel decides to take her body to el-Kantara for burial because, as he says, “the French cemetery at Touggourt is a hideous place, half devoured by the sand.”

Another writer who spent time exploring North Africa was Norman Douglas. like Gide’s, Douglas’ journeys were made in part to leave something of Europe behind. Although his first visit to the Sahara was ten years earlier, it was a three-month period Douglas spent in the south of Tunisia during the winter of 1909-10 that forms the basis of his book about the region,

Fountains in the Sand· Rambles among the Oases of Tunisia

. Douglas’ only book with a North African theme, Fountains was published in 1912, five years before

South Wind

, the novel that established his literary fame. Despite being full of the casual racism which was the norm at the time for example, he scathingly dismisses the locals saying, “In a land where no one reads or writes or thinks or reasons, where dirt and insanity are regarded as marks of divine favour, how easy it is to acquire a reputation for holiness” -

Fountains

remains a text that offers useful insights about the country as it was then.

Touggourt, Algeria

Douglas also makes himself the target of certain unflattering observations, although one cannot be entirely sure if these are genuine or literary artifice. Giving his thoughts regarding the Arab work ethic, Douglas tries to convince us that he is the same as those he is slandering, remarking: “The chief mental exercise of the Arab, they say, consists in thinking how to reduce his work to a minimum. Now this being precisely my own ideal of life, and a most rational one, I would prefer to put it thus: that of many kinds of simplification they practise only one-omission, which does not always pay.” His views on local women are no less damning: “The Arab woman is the repository of all the accumulated nonsense of the race, and her influence upon the young brood is retrogressive and malign.” It should be said that Douglas shows no less disdain for the Europeans he meets, and for what he sees as their ill-informed view of the local population.

Yet when Douglas turns his attention to the desert landscape, his descriptions are often moving. Writing about the silence of the desert, he offers a poetic meditation:

Face to face with infinities, man disencumbers himself. Those abysmal desert-silences, those spaces of scintillating rock and sand-dune over which the eye roams and vainly seeks a point of repose, quicken his animal perception; he stands alone and must think for himself-and so far good. But while discarding much that seems inconsiderable before such wide and splendid horizons, this nomad loads himself with the incubus of dream-states.

When Agatha Christie, or Agatha Miller as she then was, first journeyed to Egypt with her mother in 1910, the trip remained lengthy but it was a destination which the moderately well off could afford, leaving northern Europe in search of winter sunshine. Indeed, one of the reasons Agatha Miller’s mother decided to spend a winter in Egypt was that her daughter’s coming-out as a debutante would be more affordable than in England.

During her first visit to the Middle East Agatha showed little interest in either the Sahara or the monuments of Ancient Egypt. Writing in her autobiography about her mother’s attempts to take her to Luxor, she confessed, “I protested passionately with tears in my eyes. The wonders of antiquity were the last thing I cared to see.” Yet her first sight of the Sahara obviously had some impact on her because, on her return to England, she wrote her first, unpublished, novel, which she set in Egypt and called

Snow on the Desert

.

She returned to Egypt twice in the 1930s, with her husband, the archaeologist Max Mallowan. By now her interest in the desert had grown, and she used it to good effect when writing

Death Comes as an End

, published in 1945, and a play,

Akhenaton

, which was not published until1973. Christie’s only murder mystery with an ancient setting, she described

Death Comes as an End

as “my 11th_Dynasty Egyptian Detective Story’’. During the war Agatha and Max were separated on account of his wartime service, which took him, via Cairo, to the Sahara in Tripolitania and the Fezzan.

Edith Wharton also ventured into the Sahara in the early days of tourism first travelling to Algeria and Tunisia in 1914, having already moved permanently from America to settle in France. When Wharton went to Morocco three years later, she was working for people whom the war had made refugees; she was also the doyenne of American literary society. The opportunity for her Moroccan journey followed an invitation from General Hubert Lyautey, then serving as Resident-General of the French Protectorate in North Africa, and to whom Wharton dedicated

In Morocco

, her 1920 book about her travels there. Lyautey was a leading figure in France’s expansion into Algeria, a political position which matched Wharton’s view of herself as a “rabid imperialist”. Parts of

In Morocco

read uncomfortably like a panegyric to the general (“It is not too much to say that General Lyautey has twice saved Morocco from destruction’’), and displaying extreme prejudice against the local population, Jews and Muslims alike, Wharton saw the region’s only hope to lie in the French “civilizing mission”.

If one can ignore her far-from-neutral assessment of the colonial experiment, Wharton’s views on travelling at that time are interesting, coming, as she notes, at a unique moment in the history of tourism and the Sahara:

The next best thing to a Djinn’s carpet, a military motor, was at my disposal every morning; but war conditions imposed restrictions, and the wish to use the minimum of petrol often stood in the way of the second visit which alone makes it possible to carry away a definite and detailed impression... These drawbacks were more than offset by the advantage of making my quick trip at a moment unique in the history of the country; the brief moment of transition between its virtually complete subjection to European authority, and the fast-approaching hour when it is thrown open to all the banalities and promiscuities of modern travel.

Travelling to the Tunisian Sahara in 1921, Carl Gustav Jung wanted to believe he was travelling to a place that existed somehow outside of time, not a realm transformed by European occupation. As he wrote in

Memories, Dreams, Reflections

, “In travelling to Africa to find a psychic observation post outside the sphere of the European I unconsciously wanted to find that part of my personality which had become invisible under the influence and the pressure of being European.” The Sahara, for Jung, represented something unchanging, literally time-less. He remarked: “While I was still caught up in this dream of a static, age-old existence, I suddenly thought of my pocket watch, the symbol of the European’s accelerated tempo. This, no doubt was the dark cloud that hung threatening over the heads of these unsuspecting souls. They suddenly seemed to me like the game who do not see the hunter but, vaguely uneasy, scent him-’him’ being the god of time who will inevitably chop into the bits and pieces of days, hours, minutes, and seconds that duration which is still the closest thing to eternity.” Warming to his theme of time and the desert, Jung went further: