The Sagas of the Icelanders (112 page)

Read The Sagas of the Icelanders Online

Authors: Jane Smilely

Íslendingspdttursögufroda

*

It so happened one summer that a bright young Icelandic man came to the king and asked to be taken into his care. The king asked if he knew any lore, and he claimed that he could tell stories. The king then said that he would keep him, but that he would be obligated always to entertain anyone who asked him. He did so and grew popular among the king’s men. They gave him clothes, and the king gave him weapons. And so it went until Yule.

Then the Icelander grew sad. The king asked why, and he answered that he was just in a bad mood.

‘That can’t be it,’ the king said, ‘so let me guess. I would guess that you have run out of stories to tell. This winter you have always entertained anyone who has asked you. Now you are upset that you’re out of stories at Yule.’

‘It is just as you say,’ he replied. ‘I have only one story left, and that one I dare not tell here, for it is the story of your travels.’

The king said, ‘And that is exactly the story I most desire to hear. Now don’t tell any stories until Yule, since people are busy now. But on the first day of Yule begin the story, and tell a little bit of it. I will arrange it with you so that the story lasts as long as Yule. Now a lot of drinking takes place at Yuletide, and there is little time for sitting around and hearing stories. Nor will you be able to see, while you are telling, whether I am pleased or not.’

So it happened, and the Icelander told his story. He began on the first day of Yule and spoke for a while. But the king soon told him to stop.

Then people started drinking, and many of them discussed how bold it was of the Icelander to tell that story, or how they thought the king would

like it. Some thought that he told the story well, but some were less patient. And so it went on during Yule.

The king made sure that people listened carefully, and under his direction the story and Yule ended at the same time.

On Twelfth Night, after the story had ended earlier in the day, the king said, ‘Aren’t you curious, Icelander, to know how I liked the story?’

‘I am afraid to know, my lord,’ he answered.

The king said, ‘I liked it very much, and it was no worse than the matter permitted. But who taught you the story?’

He answered, ‘It was my habit out in my country to travel each summer to the Thing, and I learned part of the story each summer from Halldor Snorrason.’

‘In that case it is no wonder,’ the king said, ‘that you know it well. Your luck will now be with you. Be welcome here with me, and I will grant you whatever you want.’

The king secured him good wares, and he grew into vigorous manhood.

Translated by

ANTHONY MAXWELL

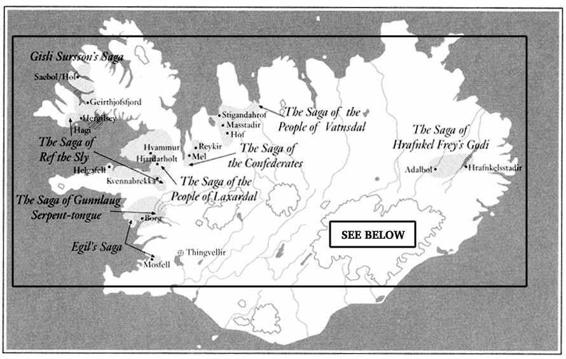

Saga Sites in Iceland

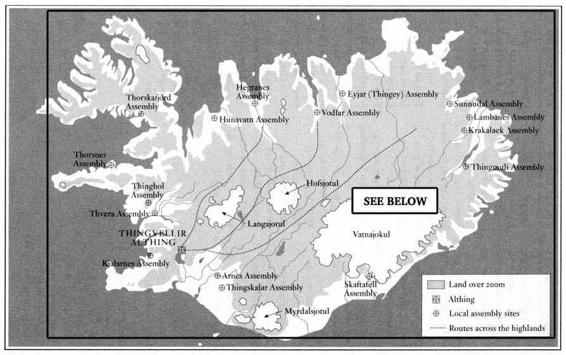

Assembly Sites

- Harald Fair-hair –932

- Erik Blood-axe 930–34

- Hakon Haraldsson, King Athelstan’s foster-son 934–60

- Harald Grey-cloak 960–75

- Hakon Sigurdarson the Powerful 975–95

- Olaf Tryggvason 995–1000

- Eirik (d. 1013) and Svein Hakonarson 1000–1015

- Olaf Haraldsson the Saint 1014–30

- Svein Knutsson (son of Canute the Great) 1030–35

- Magnus Olafsson the Good 1035–47

- Harald Sigurdarson the Stern 1046–66

- Magnus Haraldsson 1066–9

- Olaf the Quiet 1067–93

- Magnus Bare-leg 1093–1103

- Olaf (d. 1116), Eystein (d. 1122) and Sigurd Jerusalem-farer, sons of Magnus 1103–30

- Magnus Sigurdarson the Blind 1130–35

- Harald Magnusson Gilli 1130–36

- Sigurd (d. 1155), Eystein (d. 1157) and Ingi Haraldsson 1136–61

- Hakon Broad-shoulder Sigurdarson 1157–62

- Magnus Erlingsson 1161–84

- Gorm the Old –940

- Harald Black-tooth Gormsson –

c

. 986 - Sveinn Fork-beard Haraldsson 986–1014

- Harald Sveinsson 1014–18

- Knut (Canute) Sveinsson the Great 1018–35

- Hardicanute 1035–42

- Magnus Olafsson the Good 1042–7

- Svein Ulfsson 1047–74

- Harald Hein Sveinsson 1074–80

- Knut the Saint 1080–86

- Olaf Hunger 1086–95

- Eirik the Good 1095–1103

- Nikulas 1103–34

- Eirik Eimuni 1134–7

- Eirik Lamb 1137–46

- Svein Svidandi 1146–57

- Knut Magnusson 1166–7

- Valdemar Knutsson the Old 1157–82

- Ethelred I, King of Wessex 866–71

- Alfred the Great, King of Wessex 871–99

- Edward the Elder, King of Wessex 899–924

- Athelstan the Faithful 925–39

- Edmund I 939–46

- Eadred 946–55

- Eadwig 955–9

- Edgar 959–75

- Edward the Martyr 975–8

- Ethelred II, the Unready 978–1013; 1014–16

- Svein Fork-beard 1013–14

- Edmund II, Ironside 1016

- Knut (Canute) Sveinsson the Great 1016–35

- Harold I 1035–40

- Hardicanute 1040–42

- Edward the Confessor 1042–66

- Harold Godwinson (II) 1066

- William I, the Conqueror 1066–87

- William II 1087–1100

- Henry I 1100–1135

- Stephen 1135–54

- Settlement of Iceland begins

c

. 870 - Battle of Havsfjord (Harald Fair-hair takes control of Norway) c

. 885–900 - Establishment of the

Althing c

. 930 - Beginning of the Commonwealth 930

- Battle of Brunanburh I Wen Heath in England (.9V

- Division of Iceland into Quarters

c. 965 - Discovery of Greenland 985–6

- Christianity accepted in Iceland 1000

- Battle of Svold (the death of King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway) c

. 1000 - First trips to Vinland

c

. 1000–1011 - Agreement between the Icelanders and Olaf Haraldsson the Saint, King of Norway 1020–30

- Battle of Stiklestad in Norway (the death of King Olaf Haraldsson the Saint)

1030 - Isleif Gizurarson becomes the first bishop of Iceland (at Skalholt) 1056

- Battle of Stamford Bridge (the death of King Harald Sigurdarson in England)

1066 - Ari Thorgilsson the Learned born

c

. 1068 - Jon Ogmundarson becomes the first bishop of Holar (in the north of Iceland) 1106

- Íslendingabok

(The Book of Icelanders) written by Ari the Learned

c

. 1122–33 - First Kings’ Sagas compiled

c

. 1150 - Snorri Sturluson born 1179 (d. 1241)

- First Sagas of Icelanders compiled

c

. 1220 - First Legendary Sagas (

fornaldarsögur

) compiled

c

. 1220 - Heimskringla

compiled by Snorri Sturluson

c

. 1220–30 - Codex Regius

of the Eddic poems compiled

c

. 1260 - End of the Commonwealth 1262

- Módruvallabók

codex of the sagas compiled mid-fourteenth century

- Ulfljot –930

- Hrafn Haengsson (son of Ketil Haeng) 930–49

- Thorarin Ragi’s Brother Oleifsson 950–69

- Thorkel Moon Thorsteinsson 970–84

- Thorgeir Thorkelsson the Godi, from Ljosavatn 985–1001

- Grim Svertingsson 1002–3

- Skafti Thoroddsson 1004–30

- Stein Thorgestsson 1031–3

- Thorkel Tjorvason 1034–53

- Gellir Bolverksson 1054–62

- Gunnar Thorgrimsson the Wise 1063–5

- Kolbein Flosason 1066–71

- Gellir Bolverksson 1072–4

- Gunnar Thorgrimsson the Wise 1075

- Sighvat Surtsson 1076–83

- Markus Skeggjason 1084–1107

- Ulfhedin Gunnarsson 1108–16

- Bergthor Hrafnsson 1117–22

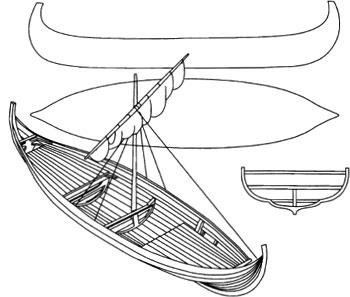

No full-sized ships have been found in excavations in Iceland, only small boats which have been placed in graves. Several types of ships are mentioned in the sagas, however, and it is obvious that they had a variety of purposes, ranging from the local ferrying of travellers to foreign warfare, trade and the transportation of cargo across the open sea.

It is worth noting that, unlike today’s ocean-going vessels, the ships of this time were open to the elements and had no decks in the modern sense of the word. Navigation was largely carried out by means of the sun, stars, landmarks, and knowledge of birds and whales. The ships were propelled by the wind (with the use of large sails) and human strength (through the use of oars). They were steered by a single rudder which was attached to the starboard side of the vessel, near the stern.

There seems to have been a distinction, though not a firm one, between a ‘ship’ and a ‘boat’, in that a ship {

skip

) was seen as being a vessel that usually had more than twelve oars, while a boat {

bdtur

) had fewer than twelve. There was no sharp difference between warships and trading ships, since trading ships were sometimes used for warfare. Nonetheless, warships tended to be large, long and slender, and designed for both sailing and rowing. They were usually divided laterally into spaces for pairs of rowers, known as

rúm

(literally ‘rooms’). The warships of kings, such as the famous Long Serpent and Bison belonging to Olaf Tryggvason and Olaf Haraldsson of Norway, often had more than thirty ‘rooms’, that is more than sixty oars. Trading vessels tended to be somewhat different.

All trading ships were broader in proportion to their length than warships. They had a rounder form, a bigger freeboard and a deeper draught than the longships. As they were designed almost exclusively for sailing, in most cases the mast was fixed. On the permanent deck fore and aft it was possible to stand or sit in a row if necessary, for here (but not amidships) there were oar-holes in the ship’s side. All the middle part of the ships was occupied by the cargo.

(Brogger and Shetelig,

p. 179

)

Figure 1. Knorr

It is unlikely that warships ever sailed to Iceland, but the saga heroes are often said to have gone raiding on their trips abroad. The most important ship for the Icelanders was the knorr {

knörr

). Smaller, broad boats of a similar kind were used for centuries in Iceland, especially in the area around Breidafjord. Such boats might well be similar to the smaller cargo vessels {

byrdingar

) mentioned in the sagas. The most common ships:

The cargo vessel was short and broad, smaller than the knorr, and mainly intended for coastal trade, although on occasion such vessels seem to have been ocean-going. They tended to have crews of between twelve and twenty men. The vessel known as Skuldelev 3, like the other Skuldelev ships now on display in Roskilde, is probably an example of a cargo vessel. It is

c

. 13.8m long and 3.3m in the beam.

The knorr was a large, wide-bodied, sturdy, ocean-going cargo ship, the biggest of the trading ships. The settlers of Iceland and Greenland, and the Vinland explorers, seem to have most commonly used the knorr, which was capable of carrying not only people but also livestock, cargo and large amounts of supplies. An example of the knorr (referred to as Skuldelev 1) was found in Roskilde fjord in Denmark and is on display in Roskilde. This is

c

. 16.3m long and

c

. 4.5m in the beam. (See

Figure 1

.)

The expression longship (

langskip

) was a collective, general term used for large warships, more than thirty-two oars. Some of these were of great size, like King Olaf Tryggvason’s Long Serpent, which is said to have had thirty-four ‘rooms’,

Figure 2. Warship

making a total of sixty-eight oarsmen, and probably also had space for additional warriors. As in the case of the warship (

karfi

) (see below), the size was usually indicated by the number of places for rowers. The ship known as Skuldelev 2, now on display in Roskilde, is thought to be a longship. This vessel, which probably was 28–9m long and

c

. 4.5m in the beam, might have carried between fifty and sixty men. Nonetheless, it is somewhat smaller than many of the Norwegian longships described in the sagas.

The warship was generally smaller than the longships owned by kings and great chieftains. The size clearly varied: they range from a warship with sixteen oars on each side, mentioned in the

Saga of Grettir the Strong

, to the warship with six oars on each side which is said to have been owned by a child in

Egil’s Saga

. The Gokstad and Oseberg ships, on display in Oslo, have been identified as being this type of vessel. The Gokstad ship has sixteen oars on each side, and was 23.3m long and 5.25m in the beam. (See

Figure 2

.)

The famous dragon (

dreki

) was also a warship. The term is mainly used in later, more fictive sagas, but makes an early appearance in

Egil’s Saga

. The dragon, however, was not a specific type of ship, rather a form of description. It originates in the occasional use of apparently removable dragon heads (and sometimes even tails) which were attached to the prows (and sterns) of vessels. According to an old Icelandic law, dragon heads had to be removed from ships which were heading towards land, so as not to frighten the local nature spirits that guarded Iceland. Various other expressions for ships that appear in the sagas: The ferry (

ferya

) was used for cargo and local transport, but we have no description of its size or what it looked like.

The general term trading vessel (

kaupskip

) simply refers to any vessel engaged in trade (

kaup

). The term was probably usually synonymous with the word knorr.

The expressions large warship (

skeid

), light ship/boat/smack (

skiita

) and swift warship (

snekkja

) are, as Brdgger and Shetelig have pointed out (p. 169), hardly classifications by size or equipment, but rather tend to be ‘used merely in a transferred sense as indistinct imagery’.

See further: Bregger, A. W. and Shetelig, H.,

The Viking Ships

. Oslo, 1951.

Foote, Peter and Wilson, D. M.,

The Viking Achievement

. London, 1979.

Campbell, James Graham,

The Viking World

. London, 1980.