The Real History of the End of the World (27 page)

Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

13.59Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Now living on land the group had bought in a town near Albany, New York, Lee and her brother, William, made a proselytizing trip through New England. While they were still greeted with ridicule in most places, the religious climate had changed to be more favorable to the Shakers. In the midst of the Revolution and just afterward, a movement had spread through New England known as the New Light Stir. This was a follow up to the Great Awakening of the 1740s. While not specifically millennial, this movement was grounded in the Protestant belief that “God visits ordinary people with the âNew Light' of transfiguring grace and revelation.”

8

One disillusioned New Lighter, who had expected the end of the world in 1779, was Joseph Meacham. Meacham found hope in the Shaker philosophy and became Ann Lee's “first born son in America.”

9

8

One disillusioned New Lighter, who had expected the end of the world in 1779, was Joseph Meacham. Meacham found hope in the Shaker philosophy and became Ann Lee's “first born son in America.”

9

By the time of Lee's death in 1784, there were eleven Shaker “families,” households of men, women, and children under the direction of an Elder and an Eldress. Apart from a belief in the approach of the millennium and strict celibacy, it's not clear what the theology of the Shakers consisted of. Lee could not read or write and had forbidden her followers to write tracts. However, after she died, the sect had been the subject of sensationalist books by former disciples. Joseph Meacham decided that the life of Mother Ann and the history of the group should be compiled in their own defense. Lee was being represented as a “pretended âSecond Christ', a fortuneteller, a drunkard, a false prophet or miracle worker and a âwoman in authority over men.' ”

10

Considering that homemade whiskey was the main form of central heating in colonial America, the charge of drinking may have had some base. She might also have pled guilty to the last charge, but not to its being a bad thing.

10

Considering that homemade whiskey was the main form of central heating in colonial America, the charge of drinking may have had some base. She might also have pled guilty to the last charge, but not to its being a bad thing.

This is the point in the story at which the historian has to walk carefully. All of the information we have on what Ann Lee believed herself to be comes from the memories of those who knew her. In line with the popular belief in personal revelation, she seems to have felt that Christ was with her at all times. She apparently referred to him as her “husband” and “lover,” something any medieval nun would have understood.

In the years after her death her followers seemed to have revised this relationship with Jesus, sometimes diminishing it. In Meacham's 1790 statement of the principles of the church, he stated that the Shakers were the “fourth dispensation” and that Christ had not returned in the flesh but in spirit to the Shaker community as a whole.

11

He gives the date for this Second Coming as having begun in 1747, with the Shaking Quakers, James and Jane Wardley.

12

11

He gives the date for this Second Coming as having begun in 1747, with the Shaking Quakers, James and Jane Wardley.

12

However, by the early 1800s, a number of Shakers were convinced that Ann Lee had not just walked with Christ, but was Christ reborn in a female body. The preface to the 1816 book of reminiscences of Mother Ann begins, “When the time was fully come, according to the appointment of God, Christ was again revealed . . . in the person of a female. This extraordinary woman, whom her followers believe God had chosen, and in whom Christ did visibly make his second appearance, was Ann Lee.”

13

13

This divine presence was expressed in various ways by Lee's followers. One, Benjamin Young, was the first Shaker to write that God was dual in nature, He stated that there was a Holy Mother Wisdom who co-existed with the Creator Father.

14

The First Advent was the male side of God; therefore, the second would logically be female.

14

The First Advent was the male side of God; therefore, the second would logically be female.

Even more, like Jesus, Ann Lee was poor, persecuted, and never wrote down her teachings. She let her apostles spread and preserve the Word.

Some Shakers were firm in their belief in Lee's divinity. Others worked around the concept in various ways. Some said that Lee was merely the “first witness” of the Second Coming. The 1827

Testimonies

gives the doctrine of male and female in one god and states that Ann Lee is the spirit of Christ in female form. Yet they also add that they “reject the doctrine of the Trinity, of the bodily resurrection, and of an atonement for sins. They do not worship either Jesus or Ann Lee, holding both to be simply elders in the Church, to be respected and loved.”

15

Clearly, the question of Lee's nature was one that varied according to the believer. It also changed over time, being downplayed by the end of the nineteenth century.

Testimonies

gives the doctrine of male and female in one god and states that Ann Lee is the spirit of Christ in female form. Yet they also add that they “reject the doctrine of the Trinity, of the bodily resurrection, and of an atonement for sins. They do not worship either Jesus or Ann Lee, holding both to be simply elders in the Church, to be respected and loved.”

15

Clearly, the question of Lee's nature was one that varied according to the believer. It also changed over time, being downplayed by the end of the nineteenth century.

The Shakers also spoke of Ann Lee as “the woman clothed with the sun” of Revelation 12. As several modern scholars have pointed out, she was glorified by the Shakers as a woman rather than as the mouthpiece for a male god.

16

This has led some to feel that the Shakers were proto-feminists. Of course, they could also be considered proto-communists and early practitioners of modern dance. I think it's better to understand people in their own time rather than to force them into ours. It is certain that women were given an equal say in the running of the community. However, in the division of labor, women did cooking, cleaning, laundry, canning, and lacemaking whereas men were blacksmiths, farmers, broom makers, and mechanics. Work was assigned along traditional gender lines, but it appears that both women's and men's work were given equal value. Perhaps taking sex out of the mix allowed a more balanced view.

16

This has led some to feel that the Shakers were proto-feminists. Of course, they could also be considered proto-communists and early practitioners of modern dance. I think it's better to understand people in their own time rather than to force them into ours. It is certain that women were given an equal say in the running of the community. However, in the division of labor, women did cooking, cleaning, laundry, canning, and lacemaking whereas men were blacksmiths, farmers, broom makers, and mechanics. Work was assigned along traditional gender lines, but it appears that both women's and men's work were given equal value. Perhaps taking sex out of the mix allowed a more balanced view.

One constant in Shaker theology is that they believed that they were living in the last millennium. For this reason, once they had become full members of the community, Shakers felt that they must live sinless lives, as there could be no second chances given to back sliders. They were the final church and it was their duty to see the world through to the Final Judgment. The 1806

Testimony,

written by a member of an Ohio Shaker community, states “He that commiteth sin is of the devil, & God must reject such a one for xt.s [Christ's] sake, because xt [Christ] and belial [Satan] can have no concord.”

17

Testimony,

written by a member of an Ohio Shaker community, states “He that commiteth sin is of the devil, & God must reject such a one for xt.s [Christ's] sake, because xt [Christ] and belial [Satan] can have no concord.”

17

They hoped that they could bring about a heaven on earth by convincing the rest of the world to join them. When all lived sinless lives, without reproduction, then it would be a world of saints, ready for the Last Judgment and eternal life in heaven.

18

18

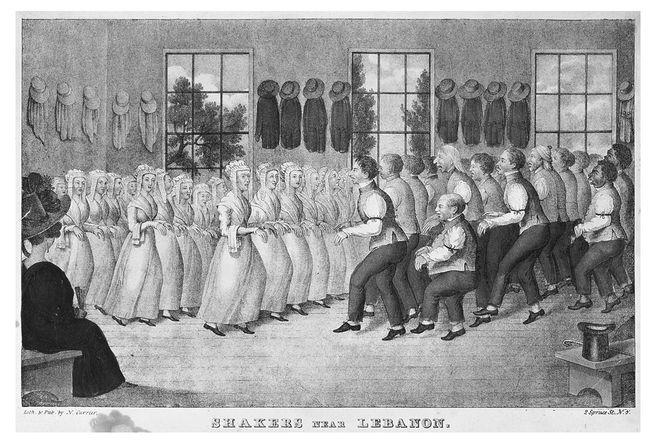

As time passed the Shakers became more accepted. They were known for their hospitality, taking in and feeding strangers as a duty. Their craftsmanship and practical inventions were much admired.

19

They were clean, thrifty, and honest in their business dealings. The marching and dancing during their services became quaint rather than bizarre. Later evangelical movements had made ecstatic shouting and speaking in tongues more commonplace in the American religious experience.

19

They were clean, thrifty, and honest in their business dealings. The marching and dancing during their services became quaint rather than bizarre. Later evangelical movements had made ecstatic shouting and speaking in tongues more commonplace in the American religious experience.

Currier, Nathaniel (1813-1888). Shakers dance near Lebanon. Lithograph. Location: Private Collection.

Giraudon / Art Resource, New York

Giraudon / Art Resource, New York

The high point in Shaker population occurred around 1840 with about five thousand members. After that, the communities began a slow loss of members. Not enough people joined the group to keep the numbers up. Children adopted by the Shakers often left when they reached adulthood. The days were strictly regimented to prayer and work. Life as a Shaker required faith and discipline, although for many the fellowship of the community was an important factor. They tried to live as saints with tolerance for the quirks of others.

20

20

As of 2006, there was one Shaker community left, one of the oldest, in Sabbathday Lake, Maine. There are four members, two men and two women. They try to maintain the Shaker way of life in the midst of tourists and encroaching developments.

21

They are not adverse to modern technology, which makes sense considering how many devices they invented to make work easier. They even have a website.

22

In 2009, they hosted a music festival.

21

They are not adverse to modern technology, which makes sense considering how many devices they invented to make work easier. They even have a website.

22

In 2009, they hosted a music festival.

What hasn't changed is the essential belief of the Shakers. “It teaches above all else that God is Love and that our most solemn duty is to show forth that God who is love in the World. Shakerism teaches God's immanence through the common life shared in Christ's mystical body.”

23

23

The last Shakers have not given up hope that the rest of the world will come around to this belief, thereby bringing on the millennium.

1

Rosemary D. Gooden, “The Shakers: A Brief Historical Sketch,” in

Locating the Shakers: Cultural Origins and Legacies of an American Religious Movement

ed. Mick Gridley and Kate Bowles (Exeter, UK: Exeter University Press, 1990), 1. See also Edward Deming Andres,

The People Called Shakers: A Search for the Perfect Society

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1953); and Stephen A. Marini,

Radical Sects of Revolutionary New England

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982).

Rosemary D. Gooden, “The Shakers: A Brief Historical Sketch,” in

Locating the Shakers: Cultural Origins and Legacies of an American Religious Movement

ed. Mick Gridley and Kate Bowles (Exeter, UK: Exeter University Press, 1990), 1. See also Edward Deming Andres,

The People Called Shakers: A Search for the Perfect Society

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1953); and Stephen A. Marini,

Radical Sects of Revolutionary New England

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982).

3

Gooden, 1.

Gooden, 1.

4

Op. cit.

Op. cit.

5

Clark, 333.

Clark, 333.

6

Tisa J. Wenger, “Female Christ and Feminist Foremother: The Many Lives of Ann Lee,”

Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion

18, no. 2 (2002): 6.

Tisa J. Wenger, “Female Christ and Feminist Foremother: The Many Lives of Ann Lee,”

Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion

18, no. 2 (2002): 6.

7

Gooden, 2.

Gooden, 2.

8

Charles Sellers,

The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1814-1846

, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1991), 30.

Charles Sellers,

The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1814-1846

, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1991), 30.

9

Gooden, 3.

Gooden, 3.

10

Jean M. Humes, “ âYe Are My Epistles': The Construction of Ann Lee Imagery in Early Shaker Sacred Literature,

Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion

8, Nn. 1 (1991): 87.

Jean M. Humes, “ âYe Are My Epistles': The Construction of Ann Lee Imagery in Early Shaker Sacred Literature,

Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion

8, Nn. 1 (1991): 87.

11

Clark, quoting from the 1808 manifesto

The Testimony of Christ's Second Appearing,

337-338. The other three dispensations were the antediluvians, the Jews up to Jesus, and from Jesus to Ann Lee.

Clark, quoting from the 1808 manifesto

The Testimony of Christ's Second Appearing,

337-338. The other three dispensations were the antediluvians, the Jews up to Jesus, and from Jesus to Ann Lee.

12

Wenger, 10-11.

Wenger, 10-11.

13

Quoted in Marjorie Procter-Smith, “Who Do You Say That I Am?: Mother Ann as Christ,” in

Locating the Shakers,

ed. Gridley and Bowles, 84-85.

Quoted in Marjorie Procter-Smith, “Who Do You Say That I Am?: Mother Ann as Christ,” in

Locating the Shakers,

ed. Gridley and Bowles, 84-85.

14

Humez, 86.

Humez, 86.

15

Clark, 338.

Clark, 338.

16

Procter-Smith and Humez both discuss this. Wenger argues that the elevation of Mother Ann was intended to establish authority among her successors but also notes the emphasis on the feminine.

Procter-Smith and Humez both discuss this. Wenger argues that the elevation of Mother Ann was intended to establish authority among her successors but also notes the emphasis on the feminine.

17

Stephen J. Stein, “ âA Candid Statement of Our Principles': Early Shaker Theology in the West,”

Proceedings of the American Physical Society

133, no. 4 (1989): 517. This reproduces the document with all its idiosyncratic spellings. One interesting thing about this is that Ann Lee is nowhere mentioned in it.

Stephen J. Stein, “ âA Candid Statement of Our Principles': Early Shaker Theology in the West,”

Proceedings of the American Physical Society

133, no. 4 (1989): 517. This reproduces the document with all its idiosyncratic spellings. One interesting thing about this is that Ann Lee is nowhere mentioned in it.

18

Clark, 338.

Clark, 338.

19

Among other things, they invented the clothespin (Clark, 342).

Among other things, they invented the clothespin (Clark, 342).

20

Arthur T. West, “Reminiscence of Life in a Shaker Village,”

The New England Quarterly

11, no. 2 (1938): 343-360. This presents a nostalgic view of life by a man who was raised by the Shakers and then left and later came back to teach for a time.

Arthur T. West, “Reminiscence of Life in a Shaker Village,”

The New England Quarterly

11, no. 2 (1938): 343-360. This presents a nostalgic view of life by a man who was raised by the Shakers and then left and later came back to teach for a time.

21

Stanley Chase, “The Last Ones Standing,”

Boston Globe,

July 23, 2006. Available at

www.boston.com/news/globe/magazine/articles/2006/07/23/the_last_ones_standing

. Accessed November 2009.

Stanley Chase, “The Last Ones Standing,”

Boston Globe,

July 23, 2006. Available at

www.boston.com/news/globe/magazine/articles/2006/07/23/the_last_ones_standing

. Accessed November 2009.

CHAPTER THIRTY

The Mummyjums

Their dress is very singular, long beards, close caps and

bear skins tied around them. The writer believes

them a set of deluded enthusiasts.

bear skins tied around them. The writer believes

them a set of deluded enthusiasts.

â

Sussex Register

(Newton, New Jersey, September 15, 1917)

Sussex Register

(Newton, New Jersey, September 15, 1917)

Â

Â

Â

Â

M

ummyjum

sounds to me like such a cute group, tubby little teddy bears with honey on their fur. The reality is far from my comfortable image. The name was given them by the Shakers of New Lebanon, who offered them what little hospitality they would accept. The Shakers were quite used to speaking in tongues, but their visitors' constant repetition of “my God, my God, my God, my God, What wouldst thou have me doâMummyjum, mummyjum, mummyjum, mummyjum,” must have gotten on even their tolerant nerves.

1

ummyjum

sounds to me like such a cute group, tubby little teddy bears with honey on their fur. The reality is far from my comfortable image. The name was given them by the Shakers of New Lebanon, who offered them what little hospitality they would accept. The Shakers were quite used to speaking in tongues, but their visitors' constant repetition of “my God, my God, my God, my God, What wouldst thou have me doâMummyjum, mummyjum, mummyjum, mummyjum,” must have gotten on even their tolerant nerves.

1

They called themselves “the Pilgrims” and were led by a red-bearded man named Isaac Bullard. His followers called him Prophet, and he governed them as an absolute monarch, receiving direction directly from heaven.

2

Bullard apparently came from Canada, near the Vermont border, and began his pilgrimage in Vermont.

2

Bullard apparently came from Canada, near the Vermont border, and began his pilgrimage in Vermont.

As with many small millennial groups, it's hard to be certain what they believed, other than that the end of the world was imminent. All the information about them comes from letters, newspaper accounts, and reports by people who encountered them in their wanderings.

Other books

Kansas Troubles by Fowler, Earlene

El gaucho Martín Fierro by José Hernández

Raw Blue by Kirsty Eagar

The Thief-Taker : Memoirs of a Bow Street Runner by T.F. BANKS

The Tomorrow-Tamer by Margaret Laurence

The Windsor Knot by Sharyn McCrumb

A Sliver of Shadow by Allison Pang

3 Brides for 3 Bad Boys by 3 Brides for 3 Bad Boys (mf)

Deliver by Pam Godwin

Dangerous Passion by Lisa Marie Rice